Illusions

"Forbidden

Christmas" or "The Doctor and the Patient"

Etcetera Series

Terrace Theater, The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts

Washington, DC, USA

Friday, November 12, 2004

by George Jackson

copyright

© 2004 by George Jackson

The

painted front curtain one sees before the start of the action serves as

overture. Its themes announce the distinct worlds from which Rezo Gabriadze

formed "Forbidden Christmas". There are three. The oldest world,

and it isn't very old, is that of middle class, burgherly Russia. It existed

in the late 19th Century at the end of the Czarist era, came briefly to

the fore during Kerensky's regime in the early 20th Century, and was never

quite wiped out by the Bolsheviks. The curtain's overall design, a simplified

form of Chagall's folkloristic cubism, and some of the objects depicted

on it represent that world, its possessions, comforts and concerns.

The

painted front curtain one sees before the start of the action serves as

overture. Its themes announce the distinct worlds from which Rezo Gabriadze

formed "Forbidden Christmas". There are three. The oldest world,

and it isn't very old, is that of middle class, burgherly Russia. It existed

in the late 19th Century at the end of the Czarist era, came briefly to

the fore during Kerensky's regime in the early 20th Century, and was never

quite wiped out by the Bolsheviks. The curtain's overall design, a simplified

form of Chagall's folkloristic cubism, and some of the objects depicted

on it represent that world, its possessions, comforts and concerns.

The Bolsheviks established a communist state that glorified labor. That

world appears in the factory facades and other industrial items that fleck

the curtain here and there. Perhaps the drabber patches of paint also

are meant to allude to communism. The third world is contemporary, that

of the commercial media. It is epitomized by the white silhouette of a

ballerina and the white shape of a Christmas tree star. The pros and cons

of Mr. Gabriadze's morality play are its characters' encounters with the

values of these three worlds.

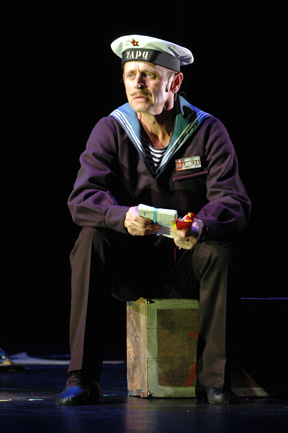

When the curtain is drawn open, not one word is spoken for the first 15

minutes or so. We are shown a sailor, he has a girlfriend ashore, their

love letters are the flag signals they send each other across the water.

She, though, is swept off her feet by a man who owns a car. When the sailor

discovers that he's been jilted, he grows sad, then goes mad. The form

his madness takes is imagining himself transformed into a car, or rather

into a chauffeur and a car. His old mother, distraught, consults a doctor.

The visual way in which the story is told up to this point is that of

pantomime theater. Action and mime are helped by music, props, lighting

effects and an occasional written sign. The mood is mellow, the props

are handsome and clever, and the overall effect is not unlike that of

a partly animated, quality film for the entire family.

After the doctor's initial encounter with the madman, we follow him home

and see how overworked he is. His patients phone at all hours. He longs

for a full night's sleep and pines for the woman whose portrait hangs

near his easy chair. In this scene the play takes a somber turn and one

senses Russian literature waiting in the wings. When spoken text enters,

it helps propel the story along. The mad patient, the car man, arrives

on the doctor's doorstop wanting to lead him to a little girl who has

swallowed iodine. Debates between the doctor and the madman are intense,

their journey to the girl is an odyssey through nature's hostilities,

communism's senselessness and the dark night of the soul—the doctor's

soul. There is a climax. The doctor, frustrated by the madman's failures

to get them to their goal and infuriated by his charming excuses and imaginative

explanations, lashes out. He bullies the madman. It works as shock therapy:

the man's illusion leaves him, he is no longer man and car in one. His

cure, though, produces a sullen, drained state.

Just then, they arrive at their destination. There is, indeed, a little

girl and she's still alive. In fact, she has almost recovered from her

poisoning. The surprise at the journey's end is that the little girl is

the patient's daughter with his ex-girlfriend. Despite the man's madness,

he and the girlfriend became reconciled and have had a happy family life

together. The only problem now is the cured man's listlessness. Miraculously,

his illusion returns and the couple's happy-ever-after life continues.

And the doctor? Well, he's been taught a lesson.

The visual part of the play, particularly the all-pantomime first stretch,

is well made even though the car driving routine is repeated too often

as the action continues. The play's second stretch, the doctor's and the

mad patient's journey, verges on great drama. Imagine a Samuel Beckett

script translated by Fyodor Dostoyevsky. It never, though, achieves its

potential. The final stretch is a let down, a stooping to holiday entertainment

fit for commercial television. We are urged to have faith. In what? It

doesn't seem to matter according to Mr. Gabriadze as long as the message

is positive. Communism is only negative as he sees it, but he equates

religion and personal madness as forces that make us feel good. Tinkerbell

can't be very far away: the sentimentality of this play's ending and recent

productions of James M. Barrie's "Peter Pan" are astoundingly

similar.

None of the actors performed in the same style. Jon DeVries struggled

valiantly to make of the doctor more than a character, giving him shadings

and highlights, dimensions and substance. Mikhail Baryshnikov's sailor

was a Petrouchka figure, simple and direct in his sadness, madness and

sullenness. It was fun to see him rev-up and road-run as the car, at least

the first couple of times he did the routine. Luis Perez (replacing Gregory

Mitchell) dispatched various deus ex machina parts with wit and charm.

Pilar Witherspoon's approach to the girlfriend was realist flat, and Yvonne

Woods was like a young corps de ballet girl playing the ballerina's mother;

in this instance she was the sailor's mother but she also got the chance

to be a snowflake (in something approaching the original "Nutcracker"

Snowflakes get-up with bangles). The author, Mr. Gabriadze, designed the

sets, props and costumes, and directed with Dmitry Troyanovsky's assistance.

Mr. Perez (ex-Joffrey Ballet) choreographed. David Meschter and again

Mr. Gabriadze were responsible for music and sound. Mr. Baryshnikov's

foundation and David Eden's company produced. The lighting, generally

fine, was by Jennifer Tipton, but she made Mr. Baryshnikov's sailor boy

look wizened at the start of the play.

Mikhail Baryshnikov, photo: Stephanie Berger:

Volume

2, No. 43

November 15, 2004

www.danceviewtimes.com

Copyright ©2004 by George Jackson

|

|

|