Theatricality. . .

FALL FOR DANCE

Alonzo King’s Lines Ballet

The Martha Graham Dance Company

New York City Ballet

Compagnie La Baraka/About LAGRAA

The Parsons Dance Company

City Center, New York, New York

October 3, 2006

By Michael Popkin

Copyright 2006 by Michael Popkin

The Fall for Dance Festival moved into its second week on Tuesday night with a program running the gamut from the New York City Ballet and the Martha Graham Dance Company on the one hand, to Alonzo King’s Lines Ballet, the Parsons Dance Company and a French modernist piece by Abou LAGRAA on the other. Considered as both choreography and performance, the results were mixed. The program was at times exciting, though too often, the works performed showed dance reduced to its lowest common denominator: raw movement, theatricality and little else.

The Fall for Dance Festival moved into its second week on Tuesday night with a program running the gamut from the New York City Ballet and the Martha Graham Dance Company on the one hand, to Alonzo King’s Lines Ballet, the Parsons Dance Company and a French modernist piece by Abou LAGRAA on the other. Considered as both choreography and performance, the results were mixed. The program was at times exciting, though too often, the works performed showed dance reduced to its lowest common denominator: raw movement, theatricality and little else.

An example of the latter was the performance by Alonzo King’s San Francisco based Lines Ballet that opened the evening with an excerpt from its “The Moroccan Project,” a dimly lit and highly athletic work for eight dancers. The work was set to traditional North African songs but there the exploration of anything of interest in this material ended. The tableau was pure Vegas, with the men bare-chested and in olive cotton skirts, the women dressed in sexy orange cocktail dresses, and the dancers emerging from the wings to cross the stage in speedy feats of acrobatic dance virtuosity that resembled very difficult calisthenics. Like Jorma Elo’s “Slice to Sharp” at NYCB last Spring, “The Moroccan Project” is instantly forgettable and better forgotten. Watching it is like hyperventilating: you get high and afterwards you don’t remember a thing. As suggested, a huge drawback is that King works with the traditional musical forms of North Africa but makes no attempt to explore the choreography of the North African dances that naturally and historically combines with this music.

Multiculturalism is very hip in the arts at the moment and has been since the 1960s. The title of “The Moroccan Project” seeks to capitalize on this; the irony is that ultimately this dance is not even a dialogue with Moroccan culture, but merely an appropriation of it for the purposes of American popular entertainment and there is nothing more narcissistic or chauvinistic, for that matter, than that.

The Martha Graham piece next on the program, “Satyric Festival Song,” a 1994 reconstruction by Graham’s company of a dance that dates from 1932, takes a more fruitful approach to indigenous material. “Festival Song” was made by Graham is an era when she was exploring Native American sources from the Southwest. The program note describes the dance as “inspired by American Indian Pueblo culture and the clowns who satirize and mock the sacred rituals.” It’s a very brief work for a single dancer (on Tuesday it was performed by Miki Ohira) who is alone onstage along with a flautist, while the score is an extended solo of staccato Pueblo melodies stitched together by Imre Weisshaus. And, while the dance vocabulary is Graham’s personal movement idiom, clear visual use is made of the Native American staccato dances and dance rhythms associated with such music. The traditional social “satiric” meanings of such dances is also played upon by Graham, her title is a double-entendre. When, for example, her pattering choreography to the native melody (foot to the floor … heel toe . . . foot to the floor) suddenly ended with a deadpan moment when the dancer balanced for a moment in retiree before falling slowly onto her side, the dance comedy and satire in the moment were two fold: “satyric” in the social context of the Pueblo dance and “satiric” in Graham’s treatment of the Pueblo material. How much more depth and resonance there was in this than in King’s method.

The Martha Graham piece next on the program, “Satyric Festival Song,” a 1994 reconstruction by Graham’s company of a dance that dates from 1932, takes a more fruitful approach to indigenous material. “Festival Song” was made by Graham is an era when she was exploring Native American sources from the Southwest. The program note describes the dance as “inspired by American Indian Pueblo culture and the clowns who satirize and mock the sacred rituals.” It’s a very brief work for a single dancer (on Tuesday it was performed by Miki Ohira) who is alone onstage along with a flautist, while the score is an extended solo of staccato Pueblo melodies stitched together by Imre Weisshaus. And, while the dance vocabulary is Graham’s personal movement idiom, clear visual use is made of the Native American staccato dances and dance rhythms associated with such music. The traditional social “satiric” meanings of such dances is also played upon by Graham, her title is a double-entendre. When, for example, her pattering choreography to the native melody (foot to the floor … heel toe . . . foot to the floor) suddenly ended with a deadpan moment when the dancer balanced for a moment in retiree before falling slowly onto her side, the dance comedy and satire in the moment were two fold: “satyric” in the social context of the Pueblo dance and “satiric” in Graham’s treatment of the Pueblo material. How much more depth and resonance there was in this than in King’s method.

Jerome Robbins’ “In the Night,” performed by New York City Ballet, followed, and, as it's a series of waltzes, it is also a work that comments upon the social dances that traditionally accompany Chopin nocturnes. For this work, City Ballet brought a cast laden with principal dancers and soloists. Rachel Rutherford and Tyler Angle were the first couple; Sofiane Sylve and Charles Askegaard the second; and Wendy Whelan and Sebastien Marcovici were the third. The music was provided by company pianist Cameron Grant.

Although Sylve and Askegaard performed brilliantly, the ballet as a whole received an uneven and at times a flat performance. In the first nocturne, Rutherford and Angle seemed to have little rapport and did not do enough to dramatize the subtle changes of mood in the piece. In the final section, Whelan and Marcovici then did exactly the opposite and overplayed, turning their characters’ emotionally wrought interchange into petulance verging on caricature. In this, they were particularly unfortunate because the young and inexperienced festival audience, most of whom were unfamiliar with this ballet, then responded to this part of the performance as though it were comedy. The tittering began in the audience when Whelan flailed her arms and attempted to escape from her lover during several tempestuous moments in the score. It reached a culmination, however, at the denouement of the ballet when the couples briefly separate and the men and women are left looking at each other in a slight echo of a similar moment in Balanchine’s “Liebeslieder Waltzes.” At this point the laughter unexpectedly became general in the theater as the audience responded to this vignette as intentional parody, interpreting the action as if it were a deadpan moment out of a Bing Crosby/Bob Hope “… On the Road To …” movie.

Although Sylve and Askegaard performed brilliantly, the ballet as a whole received an uneven and at times a flat performance. In the first nocturne, Rutherford and Angle seemed to have little rapport and did not do enough to dramatize the subtle changes of mood in the piece. In the final section, Whelan and Marcovici then did exactly the opposite and overplayed, turning their characters’ emotionally wrought interchange into petulance verging on caricature. In this, they were particularly unfortunate because the young and inexperienced festival audience, most of whom were unfamiliar with this ballet, then responded to this part of the performance as though it were comedy. The tittering began in the audience when Whelan flailed her arms and attempted to escape from her lover during several tempestuous moments in the score. It reached a culmination, however, at the denouement of the ballet when the couples briefly separate and the men and women are left looking at each other in a slight echo of a similar moment in Balanchine’s “Liebeslieder Waltzes.” At this point the laughter unexpectedly became general in the theater as the audience responded to this vignette as intentional parody, interpreting the action as if it were a deadpan moment out of a Bing Crosby/Bob Hope “… On the Road To …” movie.

After a brief intermission, the second half of the program began with Compagnie La Baraka/Abou LAGRAA’s piece entitled “Ou Transe” (the title is French and roughly translates as a play on words meaning at the same time “Where Terror” or “Where Trance”). LAGRAA is a French choreographer of North African extraction whose last name is spelled with all capital letters and who made a dance for the Paris Opera Ballet last Spring. His dance turned out to be a very lengthy extended solo and his company at the festival turned out to be himself, costumed in loose blue pants, blue sneakers and a long blue smock with a sort of hood that could be pulled up to cover his face and head, or pulled down to expose it, at different moments in the piece. The stage was dark and heavily back lit, the environment moody, and the musical score went first from silence, then to a throbbing E-flat base like a heartbeat, and finally to a rhythmic chanting. During the silence LAGRAA began on the floor with his shirt pulled up so that he appeared masked and perhaps doing Pilades, perhaps having sex with an imaginary partner. As the score moved into the extended throbbing base he revealed his face and performed a long, convulsive and tedious solo. After what seemed to be an interminable period, when the music finally turned into a chant, he pulled the hood up to cover his head, and at this point began an arrhythmic twitching that, along with the costume, left him appearing to be a finger puppet with tardive dyskinesia.

After a brief intermission, the second half of the program began with Compagnie La Baraka/Abou LAGRAA’s piece entitled “Ou Transe” (the title is French and roughly translates as a play on words meaning at the same time “Where Terror” or “Where Trance”). LAGRAA is a French choreographer of North African extraction whose last name is spelled with all capital letters and who made a dance for the Paris Opera Ballet last Spring. His dance turned out to be a very lengthy extended solo and his company at the festival turned out to be himself, costumed in loose blue pants, blue sneakers and a long blue smock with a sort of hood that could be pulled up to cover his face and head, or pulled down to expose it, at different moments in the piece. The stage was dark and heavily back lit, the environment moody, and the musical score went first from silence, then to a throbbing E-flat base like a heartbeat, and finally to a rhythmic chanting. During the silence LAGRAA began on the floor with his shirt pulled up so that he appeared masked and perhaps doing Pilades, perhaps having sex with an imaginary partner. As the score moved into the extended throbbing base he revealed his face and performed a long, convulsive and tedious solo. After what seemed to be an interminable period, when the music finally turned into a chant, he pulled the hood up to cover his head, and at this point began an arrhythmic twitching that, along with the costume, left him appearing to be a finger puppet with tardive dyskinesia.

The evening recovered from this low point and concluded with the Parsons Dance Company performing “Swing Shift” — a joyous and theatrically vital work with beautiful sculptural lighting provided by Parsons’ collaborator in the formation of his company, Howell Binkley, and with a movement palate inspired by Parson’s mentor, Paul Taylor (of whose company Parsons is an alumnus). “Swing Shift” benefits from a lovely dancing score by the contemporary, Julliard trained composer Kenji Bunch. Bunch is a violinist and the score shows it, his long violin and cello lines, backed by orchestration in which a synthesizer participates, create flowing legato melodies that suit the tenor of Parsons’ choreographic line. The brilliant lighting scheme consists of flooding the stage with colored light from overhead and contrasting this with hot spotlights from the corners to create a warm three dimensional space and an attractive atmosphere that sets of the dancers so that you see them, the eye is attracted to them. Changes of overall color are used to create sequences of dances, mainly for four couples and a single odd-girl out who begins and ends the piece in a cone of spotlight. Parsons also shows skill in getting his dancers onto and off of the stage and punctuates his duets with larger ensembles. If the dance went on far too long and had too many parts — Parsons seems to belong to the Peter Martins’ “More is More” school of composition — his work had both a structure and a visual interest missing from King’s and LAGRAA’s dances and I would gladly see more of it.

The evening recovered from this low point and concluded with the Parsons Dance Company performing “Swing Shift” — a joyous and theatrically vital work with beautiful sculptural lighting provided by Parsons’ collaborator in the formation of his company, Howell Binkley, and with a movement palate inspired by Parson’s mentor, Paul Taylor (of whose company Parsons is an alumnus). “Swing Shift” benefits from a lovely dancing score by the contemporary, Julliard trained composer Kenji Bunch. Bunch is a violinist and the score shows it, his long violin and cello lines, backed by orchestration in which a synthesizer participates, create flowing legato melodies that suit the tenor of Parsons’ choreographic line. The brilliant lighting scheme consists of flooding the stage with colored light from overhead and contrasting this with hot spotlights from the corners to create a warm three dimensional space and an attractive atmosphere that sets of the dancers so that you see them, the eye is attracted to them. Changes of overall color are used to create sequences of dances, mainly for four couples and a single odd-girl out who begins and ends the piece in a cone of spotlight. Parsons also shows skill in getting his dancers onto and off of the stage and punctuates his duets with larger ensembles. If the dance went on far too long and had too many parts — Parsons seems to belong to the Peter Martins’ “More is More” school of composition — his work had both a structure and a visual interest missing from King’s and LAGRAA’s dances and I would gladly see more of it.

Leaving the theater (and indeed before the show and at intermission too), you could see that Fall for Dance is indeed succeeding in attracting an extremely diverse and young dance audience. The house was sold out on Tuesday. People were lined up in the street for cancellation tickets before the show and milling about outside during intermission trying to get in. This must encourage the festival’s organizers — after all, attracting a new dance audience is what the festival is about — and you couldn’t help finding the young crowd bright-eyed, bushy-tailed and pleasing to be around. Nonetheless this method of audience cultivation has its risks, as the striking mediocrity of portions of Tuesday’s program and the general and inappropriate laughter at the denouement of “In the Night” showed. For the sake of the quality of what we see, the companies had better be careful in their pursuit of young people to fill their seats. You get the audience you cultivate, to a certain extent the audience you educate in the world of the theater. And it remains to be seen whether the companies involved will get the audiences they are looking for; or whether the “new” audience — due to competition for its brief attention span and unformed taste — will not instead get companies that are content to reduce their “product” to what they assume they can sell. Let’s hope it’s the first and not the second alternative.

Photos, from top:

Alonzo King's Lines Ballet in "The Moroccan Project." Photo by Marty Sohl.

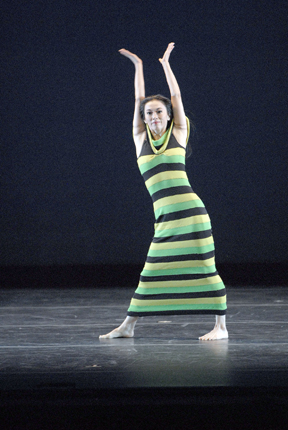

The Martha Graham Dance Company performs "Satyric Festival Song" with Miki Orihara.

Photo by Stephanie Berger.

Compagnie La Baraka/Abou LAGRAA’ in "Ou Transe".

Photo: Michael Cavalc

Wendy Whelan and Sebastien Marcovici in "In the Night." Photo by Stephanie Berger.

David Parsons Company in "Swing Shift."

Photo: David Parsons

Volume 4, No. 36

October 9, 2006

copyright ©2006 Michael Popkin

www.danceviewtimes.com