Getting it wrong

“Lady into Fox”, “Stand and Stare”, “Divine Influence”, “Verge”

Rambert Dance Company

Sadler's Wells Theatre, London

November 14 - 18 2006

by John Percival

copyright 2006 by John Percival

Fidget, fidget, fidget — that's what we get in Rambert's new London programme. They pretend to be celebrating the company's 80th birthday — but that's reckoning from when Marie Rambert made her pupil Frederick Ashton try his first apprentice choreography as a number added to a revue. More rationally, the company's real starting date was four years later, 1930, with its first seasons. Anyway, I've been watching them for 62 of those 76 or 80 years, and I can say that this programme is the worst I've ever seen from them. And Clement Crisp, who likewise has observed the company since schooldays, came to the same conclusion in his review for the Financial Times.

Anthony Crickmay.jpg) When a company does a lot of new works, you expect some of them to flop, but four premieres, all flops, on one evening, is a bit much. And they were seriously poor, the worst of all being an alleged restoration of an outstanding past work. But before we got to “Lady into Fox” we were inflicted with two pieces by company members taken into the repertoire following workshop performances. Martin Joyce made “Divine Influence” for himself and Angela Towler both wearing long white skirts and not much more. He writes that he wanted to resist the idea of “beautiful” dance as in classical ballet, and instead gives us a mass of shapeless fidgeting about. Adding insult to injury, he has the third movement of Beethoven's “Moonlight” sonata played alongside — ostensibly as an inspiration for the movement, but I was not alone in finding no relationship at all. In the other workshopped offering, “Verge”, Cameron McMillan sets five women and three men fidgeting about, sometimes with chairs, accompanied by a messy electro-acoustic score specially made by Elspeth Brooke of the Royal Academy of Music from the physical sounds of the dancers. Officially the piece is supposed to be about a major life transition and the experience of change, but I know that only from the programme note. Costumes by a fashion designer, Roland Mouret, have been added: the women are all in long black, the guys are blessed with underpants and a single sock.

When a company does a lot of new works, you expect some of them to flop, but four premieres, all flops, on one evening, is a bit much. And they were seriously poor, the worst of all being an alleged restoration of an outstanding past work. But before we got to “Lady into Fox” we were inflicted with two pieces by company members taken into the repertoire following workshop performances. Martin Joyce made “Divine Influence” for himself and Angela Towler both wearing long white skirts and not much more. He writes that he wanted to resist the idea of “beautiful” dance as in classical ballet, and instead gives us a mass of shapeless fidgeting about. Adding insult to injury, he has the third movement of Beethoven's “Moonlight” sonata played alongside — ostensibly as an inspiration for the movement, but I was not alone in finding no relationship at all. In the other workshopped offering, “Verge”, Cameron McMillan sets five women and three men fidgeting about, sometimes with chairs, accompanied by a messy electro-acoustic score specially made by Elspeth Brooke of the Royal Academy of Music from the physical sounds of the dancers. Officially the piece is supposed to be about a major life transition and the experience of change, but I know that only from the programme note. Costumes by a fashion designer, Roland Mouret, have been added: the women are all in long black, the guys are blessed with underpants and a single sock.

As apprentices, these two choreographers deserve sympathy and oblivion, but the programme's finale was by Darshan Singh Bhuller — formerly a star dancer with London Contemporary Dance Theatre, and subsequently a frequent choreographer and company director. And his contribution also was poor. It was commissioned by the Lowry, Salford (just outside Manchester), a newish arts centre containing theatres and a gallery, and meant to commemorate the painter L. S. Lowry who lived there and died 30 years ago. A very successful ballet about the reclusive Lowry was made by Northern Ballet Theatre a few years back, “A Simple Man”; choreography by Gillian Lynne, initially for television starring Christopher Gable and Moira Shearer. That was based on his life and work; Rambert's “Stand and Stare” is more or less abstract, sometimes with groupings in Lowry's manner but aiming primarily at “the emotions and intent behind Lowry's paintings” — as if we could know them. It is performed by a cast of 19 (almost the whole company) to Bartok's Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, although with lengthy silent interludes, and it didn't tell me as much about Lowry as “A Simple Man” did.

As apprentices, these two choreographers deserve sympathy and oblivion, but the programme's finale was by Darshan Singh Bhuller — formerly a star dancer with London Contemporary Dance Theatre, and subsequently a frequent choreographer and company director. And his contribution also was poor. It was commissioned by the Lowry, Salford (just outside Manchester), a newish arts centre containing theatres and a gallery, and meant to commemorate the painter L. S. Lowry who lived there and died 30 years ago. A very successful ballet about the reclusive Lowry was made by Northern Ballet Theatre a few years back, “A Simple Man”; choreography by Gillian Lynne, initially for television starring Christopher Gable and Moira Shearer. That was based on his life and work; Rambert's “Stand and Stare” is more or less abstract, sometimes with groupings in Lowry's manner but aiming primarily at “the emotions and intent behind Lowry's paintings” — as if we could know them. It is performed by a cast of 19 (almost the whole company) to Bartok's Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, although with lengthy silent interludes, and it didn't tell me as much about Lowry as “A Simple Man” did.

The programme's centrepiece was “Lady into Fox”, billed as a world premiere but listed as having choreography by Andrée Howard (who died almost 40 years ago) “restaged” by artistic director Mark Baldwin and choreologist/repetiteur Amanda Eyles. An alternative programme credit names Baldwin for “additional choreography” but still calls it a restaging. Well, I'd say it isn't any such thing.

“Without our past we are nothing” Baldwin writes, but then goes on to describe Andrée Howard's 1939 creation of “Lady into Fox” as one of the first ballets ever made for English dancers. Now Rambert's past includes, during the 1930s, about 60 ballets made for English dancers by twelve choreographers; there were also at that time about 40 given by the Vic-Wells Ballet plus others by the Camargo Society, Markova-Dolin Ballet, etc. I suppose Baldwin's ignorance of this might be caused by the wide and disgraceful neglect of our heritage. The two Royal companies do occasionally revive old works (but not enough of them). Rambert however, to mention only its best creative discoveries of that period, gives none of the ballets which Ashton created for it, hardly any of its Tudors, nor anything by Frank Staff or Walter Gore, and only now this single misrepresentation of Howard. (It is, by the way, busy ignoring also the creations by Norman Morrice and Glen Tetley which later transformed the company.)

“Without our past we are nothing” Baldwin writes, but then goes on to describe Andrée Howard's 1939 creation of “Lady into Fox” as one of the first ballets ever made for English dancers. Now Rambert's past includes, during the 1930s, about 60 ballets made for English dancers by twelve choreographers; there were also at that time about 40 given by the Vic-Wells Ballet plus others by the Camargo Society, Markova-Dolin Ballet, etc. I suppose Baldwin's ignorance of this might be caused by the wide and disgraceful neglect of our heritage. The two Royal companies do occasionally revive old works (but not enough of them). Rambert however, to mention only its best creative discoveries of that period, gives none of the ballets which Ashton created for it, hardly any of its Tudors, nor anything by Frank Staff or Walter Gore, and only now this single misrepresentation of Howard. (It is, by the way, busy ignoring also the creations by Norman Morrice and Glen Tetley which later transformed the company.)

By 1939 Howard had already made eight ballets for Rambert, including “Mermaid” and “Death and the Maiden”, both remembered with admiration, and a “Cinderella” said to have cleverly given the impression of a big spectacle on the tiny Mermaid stage. “Lady into Fox” was inspired by David Garnett's novella of that title, which would have been well known to the Ballet Club's elite audience; even so, it was thought desirable then to include, as an explanatory programme note, a quotation from the story's second paragraph: “For the sudden changing of Mrs Tebrick into a vixen is an established fact, which we may attempt to account for as we will”. No such helpful introduction is provided for today's audience, who certainly need it more, and the cast list does not indicate which characters the dancers are playing: this is stupid incompetence on somebody's part.

Although regarded as Howard's most ambitious work until then, it was on a small scale, the action entirely in the Tebricks' drawing room and garden. Those of us who saw the original version (it survived until 1950) remember a lucid and moving drama with a central role that made the reputation of Sally Gilmour, only 17 at the premiere and taking over the part at a few days' notice. She went on to become Rambert's greatest dramatic/romantic ballerina; widely regarded, for instance, as a better Giselle than any Covent Garden could then offer, a worthy inheritor of the Tudor repertoire, and creator of many further roles.

Sadly, hopes of reviving Howard's “Fox” have always failed, and this new staging doesn't succeed either. Baldwin and Eyles had access to a 12-minute amateur film, without music, of Gilmour and her original partner Charles Boyd in extracts from their roles, and have taken steps from that, but Baldwin has replaced the original music by Honneger with a new score by Benjamin Pope. I'm sure that Howard held the nice old-fashioned view that choreography consists of movement in relation to music, so she would hardly have accepted, any more than I can, that we were genuinely seeing her choreography in this rehashed context. It certainly did not look right. To make matters worse, Baldwin (citing the larger theatres in which Rambert now appears) has much enlarged the cast, giving them big, bold steps that bounce about all over the stage. His “prologue” and “epilogue” take more time than the central narration. And he hasn't even stuck to Howard's simple story. The husband is changed by his red jacket into a hunt official, giving quite the wrong relationship. The hunters, originally seen distantly through a window, now occupy centre stage; a group of hounds has been added — at least, I suppose that's what they are meant to be — and the vixen is massacred by them instead of simply bounding off to the freedom which she desires although her husband fears it will prove dangerous. New designs by Michael Howells in no way equal the originals by Nadia Benois; neither indoors nor exterior are convincing, and the clumsy new fox costume looks far less real while taking longer to change into than used to be the case. In short, this purported revival lacks all the qualities of the old ballet, and the dancers can't carry it. Maybe Pieter Symonds could have succeeded with the role as it once was (other dancers, notably Paula Hinton, did follow Gilmour in it), but she's totally at a loss in this costume and this production. Simon Cooper's desperate attempt to make sense of the husband is likewise damned by Baldwin's errors. It's all a disaster, and an insult to a choreographer who deserves to be better remembered.

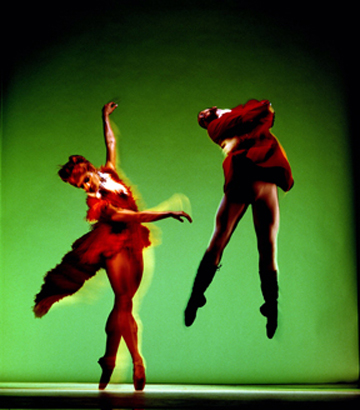

Photos all by Anthony Crickmay:

"Divine Influence."

"Stand and Stare."

"Lady into Fox."

Volume 4, No. 41

November 20, 2006

copyright ©2006 John Percival

www.danceviewtimes.com