Alone with friends

“Solo”

Nejla Y. Yatkin / NY2 Dance

Dance Place

Washington, DC, USA

November 18, 2006

by George Jackson

copyright 2006 by George Jackson

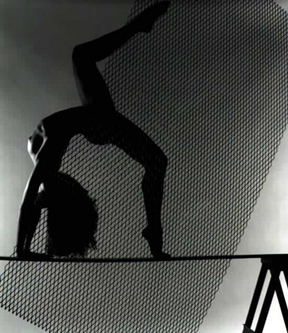

Nejla Yatkin doesn’t disappear for an instant, not within a role and not under the impact of movement. She’s a performer inside and outside, from a piercing gaze to expressive shoulder blades and from the coils of her long black hair to her finger tips and toes. As a dancer, she measures on a major scale, thanks to a strong, long body and the amplitude she sustains. Watching her can become hypnotic, even off stage.

Nejla Yatkin doesn’t disappear for an instant, not within a role and not under the impact of movement. She’s a performer inside and outside, from a piercing gaze to expressive shoulder blades and from the coils of her long black hair to her finger tips and toes. As a dancer, she measures on a major scale, thanks to a strong, long body and the amplitude she sustains. Watching her can become hypnotic, even off stage.

Despite this, Yatkin did not make things easy for herself on the Dance Place program. She tackled 12 solos, half of which she had choreographed. All the dances were to music not meant to be wasted — cello pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach, played by Robert Battey. Words, too, had a crucial function during this 2-part evening.

Part 1 consisted of Yatkin’s own choreographies to six portions of the “Cello Suite No. 1”. In the “Prelude”, Yatkin danced full-out. Much of the movement was supple in consistency, rounded in shape, even with angularity given a soft edge. There was the sense of pure motion themes being stated. Expression, feeling came to the fore in the “Allemande”. This was sensual as well as emotive dancing, with the body sometimes stretched, sometimes bent over away from the viewers, and the dancer’s arms and hands on the ground between her legs like a second pair. The “Courante” was playful, with baroque allusions, filigree movement, balleticisms. The “Sarabande” seemed meditative, with Yatkin going into and out of thinker poses and yoga postures, whereas in the “Menuett” she explored suspension with a trapeze. The final “Gigue” was sharply angular and agitated dancing.

Dancing for Yatkin is not made up of a motion vocabulary so much as of states of becoming and being. Except in the “Prelude”, she used these states to recall the past — the first and the second time she heard the Bach, who she was then and the friend, long dead, who had introduced her to this music. “Cello Suite No. 1” manages to be inventive dancing, honest thinking about music, a loving tribute to those who were, and a testament to the power of art — and it’s not pompous at all.

Part 2 of the program, to Bach’s “Cello Suite No. 2”, was diverse in a different way: six choreographers, by way of recordings, talked about their ideas of dance and then used Yatkin’s singular body and capacities to present these quite individual concepts. Juliet Seignious’s “Prelude” was stately, formal dance movement with mimetic elements (some drama, a dash of tragedy). Christian Davenport’s “Allemande” showed the dancer partially, in and out of a beam of light, and then testing her balance in stretched and squat postures. The “Courante” by Keely Garfield was more a quirky actions collage than a dance, and Tzveta Kassabova’s “Menuett” a game with chairs. The finest of the dances, Eleo Pomare’s “Sarabande”, was slow at times so that Yatkin seemed to be becoming knotted sculpture and moving against great inertia as she circled her leg. In the final “Gigue” by Lionel Popkin, Yatkin seemed a Bacchante stepping into life from an antique vase. At the end she walks off with Battey’s cello, leaving her dress behind. Amusing, “Suite No. 2” didn’t have the cumulative impact of “Suite No. 1”.

Part 2 of the program, to Bach’s “Cello Suite No. 2”, was diverse in a different way: six choreographers, by way of recordings, talked about their ideas of dance and then used Yatkin’s singular body and capacities to present these quite individual concepts. Juliet Seignious’s “Prelude” was stately, formal dance movement with mimetic elements (some drama, a dash of tragedy). Christian Davenport’s “Allemande” showed the dancer partially, in and out of a beam of light, and then testing her balance in stretched and squat postures. The “Courante” by Keely Garfield was more a quirky actions collage than a dance, and Tzveta Kassabova’s “Menuett” a game with chairs. The finest of the dances, Eleo Pomare’s “Sarabande”, was slow at times so that Yatkin seemed to be becoming knotted sculpture and moving against great inertia as she circled her leg. In the final “Gigue” by Lionel Popkin, Yatkin seemed a Bacchante stepping into life from an antique vase. At the end she walks off with Battey’s cello, leaving her dress behind. Amusing, “Suite No. 2” didn’t have the cumulative impact of “Suite No. 1”.

Battey’s playing of Bach reminded me of a man sawing Shaker furniture. What emerged had strength, dignity and a warm simplicity. He interacted with Yatkin on occasion, and what they wore was color coordinated — the white for “Suite No. 1” and black for “Suite No. 2”. Yet, even with her friends of music, memory and choreography, Yatkin remains the true soloist on stage — alone in her splendor.

Both photos of Nejla Y.Yatkin by Astrid Riecken.

Volume 4, No. 41

November 20, 2006

copyright ©2006 George Jackson

www.danceviewtimes.com