San Francisco Letter 26

San Francisco Ballet

War Memorial Opera House

San Francisco, CA

Program 6

“Night” “On Common Ground” “Rodeo”

April 13, 2007

Program 7

“Elemental Brubeck” “Concordia” “Symphony in C”

April 11, 2007

by Rita Felciano

copyright © 2007 by Rita Felciano

The two programs before San Francisco Ballet’s Season finale, “Don Quixote”, featured a world premiere each: Helgi Tomasson’s dry-as-bones “On Common Ground” and Matjash Mrozewski’s dexterous “Concordia.” Fortunately, Tomasson paired his problematic offspring with two charmers that more than earned their return, Julia Adam’s “Night”, her first SFB commission, and Agnes de Mille’s “Rodeo” — not quite as evergreen as it once was but still provides some jolly good entertainment.

The two programs before San Francisco Ballet’s Season finale, “Don Quixote”, featured a world premiere each: Helgi Tomasson’s dry-as-bones “On Common Ground” and Matjash Mrozewski’s dexterous “Concordia.” Fortunately, Tomasson paired his problematic offspring with two charmers that more than earned their return, Julia Adam’s “Night”, her first SFB commission, and Agnes de Mille’s “Rodeo” — not quite as evergreen as it once was but still provides some jolly good entertainment.

For “Common”, a bland meditation on mostly failing relationships, Tomasson plucked nine excerpts from Ned Rorem’s “String Quartet No. 4”, performed on tape. It was an odd choice of rather banal music. Its individual sections didn’t add up, and Tomasson failed to draw emotionally cohesive choreography from what should have inspired him. Sandra Woodall designed burgundy leotards for the men, tiny skirts with open-back tops for the women. Her set consisted, somewhat inexplicably, of suspended and slowly-descending bands of pale ginkgo leaves. I saw the second cast.

After an initial duet between Ruben Martin and Tiit Helimets, with Helimets something of a dour but strong persona, Molly Smolen and Sarah Van Patten burred in in unisons to partner the men and bring out the couples’ differences. These gaps came even more to the forefront in the second movement’s courting duet between the two women. Smolen, the new principal, is a compact dancer with very strong feet and a flair for drama. Her anguished reaching out contrasted strongly with Van Patten’s assertive and cool sultriness. No wonder the women proved incompatible and went their separate ways. In the subsequent male/female duets, Smolen and Martin — to a rather pretty soaring violin melody — worked out something like a halfway functioning, yet tempestuous relationship. In the finale he offered her up in out-stretched arms like a sacrificial offering to their commonality. Van Patten and Helimets’ duo — he dragged her in a split and on his back, and dumped her unto her knees — finally pulled them apart, though hesitatingly.

Also included in “Common” was a more light-hearted trio for Courtney Elizabeth Courtney Wright and Jaime Garcia Castilla. Maybe because so much of the trio distantly recalled “Apollo” theirs seemed a friendly let’s try-it encounter. I guess you can make a marriage work if you can’t tell your “wives” apart. A separate bourreeing duet for the women resembled the Doublemint Twins ad from the seventies.

The program’s opener, Adam’s 2000 “Night,” however, looked remarkably good. At that time, still quite inexperienced, Adam had commissioned an effective and appealing score by Matthew Pierce and designs from his brother, former SFB Principal Benjamin Pierce. “Night’s” vision—an exploration of dream states and nightmares — is clearly translated to the stage in ballet language that is fresh and imaginative. The choreography for the men — so often reduced to a few athletic bravura steps — is particularly varied. Maybe the piece drags a little towards the end—the heroine once to often stretching into a “Christina’s World” reach — but “Night” remains an impressive achievement for a young dance maker.

The program’s opener, Adam’s 2000 “Night,” however, looked remarkably good. At that time, still quite inexperienced, Adam had commissioned an effective and appealing score by Matthew Pierce and designs from his brother, former SFB Principal Benjamin Pierce. “Night’s” vision—an exploration of dream states and nightmares — is clearly translated to the stage in ballet language that is fresh and imaginative. The choreography for the men — so often reduced to a few athletic bravura steps — is particularly varied. Maybe the piece drags a little towards the end—the heroine once to often stretching into a “Christina’s World” reach — but “Night” remains an impressive achievement for a young dance maker.

The choreography for the three women (Elana Altman, Brooke Moore and Jennifer Stahl) used threatening spiky point work to good effect; the one for the men incorporated athletic moves—flopping fish dives, reverse push-ups, rapid floor rolls — into others that emphasized a luxurious stretched out quality. Each of the three male-female duets was built around turning-away-from each other motives.

Petite Tina LeBlanc, as the startled dreamer, floated angularly or tensed into sprints when not climbing bodies in vain attempts to escape. Despite the drama of her fetal curls or stiffening into catatonic stillness, LeBlanc’s was a curiously impersonal performance. Ruben Martin partnered her. His billowing flat-bodied stretches, upon awakening, built a good trajectory.

No doubt “Rodeo” is an important piece in the history of American Ballet. Even today Agnes de Mille’s riding. and side-to-side rocking choreography for the cowboys looks good. It must have been revolutionary to see it on a ballet stage in 1942. It made me also wonder whether “Fancy Free’s” sailors didn’t owe some of their boyish swaggers to these Western cousins. But the rest of the ballet is just terribly dated; its folk-inspired social dances look pale, its humor crude. Long, danced but didn’t convince as the Cowgirl; she looked bored. Young Matthew Stewart, however, gave a lively charming performance as the Champion Roper.

No doubt “Rodeo” is an important piece in the history of American Ballet. Even today Agnes de Mille’s riding. and side-to-side rocking choreography for the cowboys looks good. It must have been revolutionary to see it on a ballet stage in 1942. It made me also wonder whether “Fancy Free’s” sailors didn’t owe some of their boyish swaggers to these Western cousins. But the rest of the ballet is just terribly dated; its folk-inspired social dances look pale, its humor crude. Long, danced but didn’t convince as the Cowgirl; she looked bored. Young Matthew Stewart, however, gave a lively charming performance as the Champion Roper.

Mrozewski set his fresh-looking “Concordia” into a sea of darkness from which dancers emerged only to be sucked up again by blackness. While he contrasted Muriel Maffre and Pierre-François Vilanoba’s angular, fractured ballet vocabulary with Long and Gennadi Nedvigin’s traditional one, Mrozewski seems more interested in co-existence than opposition. The duets appeared like fleeting thoughts that pass by without any particular emphasis. There didn’t seem to be a trajectory to these glances at partnering but the work’s dream-like atmosphere nicely held its distinct episodes together. Two additional pairs (Joanna Mednick, Courtney Wright, James Garcia Castilla and James Sofranko) divided into shifting trios and duets and occupied a middle ground between the two styles of dancing. Mednick and Wright are still in the corps but they are refined and lovely dancers that, I’m sure, we’ll see more of in future season.

Set to “The Raven and the Nightingale” and “Technologies I” by Australian composer Matthew Hindson, “Concordia” featured grey/blue leotards — a tutu for Long — by Christopher Read and Lighting Design by Christopher Dennis.

In the program notes Mrozewski explained that he was torn between traditional ballet and the demand for the “new.” He seems equally at home in both. For the Maffre/Vilanoba duets—they danced like a single body filling in each other’s spaces—he designed short phrases and odd contact points on a variety of body levels Puffed out chest-to-chest butting could be followed by deep torso contractions with arms held out like baskets. Maffre repeatedly thrust her hip against Vilanoba’s hanging arm as if inviting some action. She scooted under his angled elbow only to hook her arm around his as if going for an arm-in-arm stroll. It’s a motive that returned again and again. And then they would simply walk away from each other — calling for a break. Much of these spiky encounters seemed friendly explorations of possibilities.

Set to “The Raven and the Nightingale” and “Technologies I” by Australian composer Matthew Hindson, “Concordia” featured grey/blue leotards — a tutu for Long — by Christopher Read and Lighting Design by Christopher Dennis.

In the program notes Mrozewski explained that he was torn between traditional ballet and the demand for the “new.” He seems equally at home in both. For the Maffre/Vilanoba duets—they danced like a single body filling in each other’s spaces—he designed short phrases and odd contact points on a variety of body levels Puffed out chest-to-chest butting could be followed by deep torso contractions with arms held out like baskets. Maffre repeatedly thrust her hip against Vilanoba’s hanging arm as if inviting some action. She scooted under his angled elbow only to hook her arm around his as if going for an arm-in-arm stroll. It’s a motive that returned again and again. And then they would simply walk away from each other — calling for a break. Much of these spiky encounters seemed friendly explorations of possibilities.

The Long/Nedvigin duets captivated by a fluid, intriguingly accented use of the idiom but even more by the clarity and restraint of its dancers. Long sometimes is not the most nuanced in her phrasing but Nedvigin seemed to inspire her. He just may be the company’s most refined danseur; having him on stage, it becomes difficult to watch anyone else.

But the evening’s highlight belonged to a much delayed reprise of Balanchine’s glorious “Symphony in C”, as staged by Elyse Borne. Not withstanding, a few imperfections in the corps, the dancers realized the music with exquisite abandon. Who else but Balanchine can make the most basic of steps — tendus front, side, back — look like the most ingenious invention. Sometimes, the constantly changing corps formations — gently pushed along by the breezy music — just about competed with the center-space soloists. This was design of the highest order, hierarchy maintained but also questioned.

But the evening’s highlight belonged to a much delayed reprise of Balanchine’s glorious “Symphony in C”, as staged by Elyse Borne. Not withstanding, a few imperfections in the corps, the dancers realized the music with exquisite abandon. Who else but Balanchine can make the most basic of steps — tendus front, side, back — look like the most ingenious invention. Sometimes, the constantly changing corps formations — gently pushed along by the breezy music — just about competed with the center-space soloists. This was design of the highest order, hierarchy maintained but also questioned.

The last movement has always struck me as particularly brilliant, though also as a little humorous because the music begins to sound repetitive, as if the composer didn’t quite know where he was going. Yet Balanchine made the music inevitable; the meandering beautifully supported the sense of his systematically gathering everyone for that final triumphant tableau.

Partnered by an elegant Gonzalo Garcia, Vanessa Zahorin was at her best—all crystalline precision in the first movement dazzling footwork. In the third the technically fierce Smolen, though somewhat oddly partnered with Pascal Molat, more than held her own in those non-stop rapid-fire jumps and turns. Sarah Van Patten and Hansuke Yamamoto danced the fourth movement well enough.

But “Symphony’s” heart is its second movement, which demands abandon and steely technique. Partnered exquisitely by Helimets who opened his arms protectively around her and let one arm float while the other secured her in those left/right arabesques, Yuan Yuan Tan came close to forgetting her admittedly spectacular technique. She let herself be carried by the Bizet. A stylistic purist friend described Tan’s performance as too  much like “Swan Like”. There is some justification to that observation; but she was uncommonly responsive to that oboe and the way she held those balances and let herself drop into those swoons captivated me completely.

much like “Swan Like”. There is some justification to that observation; but she was uncommonly responsive to that oboe and the way she held those balances and let herself drop into those swoons captivated me completely.

The program’s opener Lar Lubovitch’s “Elemental Brubeck,” apparently much loved by the dancers, is a mediocre piece from the go get that, additionally, runs out of steam in its extensive group choreography. It opened with a rather spectacular jazz solo danced with such commitment, glee and exuberance by Garcia that it made me fear that he is leaving SFB because he wants to do more of that type of show dancing. Please say that it ain’t so.

Photos (all by Erik Tomasson), from top:

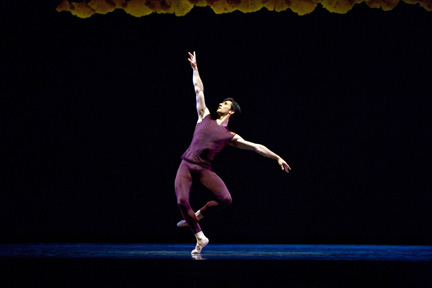

Davit Karapetyan in Tomasson's "On Common Ground."

Rory Hohenstein, Vanessa Zahorian and Tiit Helimets in Adam's "Night."

Kristin Long, here wiith Rory Hohenstein, in De Mille's "Rodeo."

Muriel Maffre and Pierre-François Vilanoba in Mrozewski's "Concordia."

Yuan Yuan Tan and Tiit Helimets in Balanchine's "Symphony In C."

San Francisco Ballet in Lubovitch's "Elemental Brubeck."

Volume 5, No. 14

April 9 2007

copyright ©2007 by Rita Felciano

www.danceviewtimes.com