Noh-Now in New York

Takeshi Kawamura’s Aoi/Komachi

Japan Society

New York, NY

March 22, 2007

copyright ©2007, Tom Phillips

The drama in Japan’s classic Noh theater comes in “the collapse of time, with elements of the past overtaking the present.” That’s a quote from program notes by Yoko Shioya, artistic director of the Japan Society. But in the opening production of her series “Noh-Now!” the present is also taking over the past, with a pair of 14th century Noh plays re-imagined by director Takeshi Kawamura in contemporary settings — a hair salon and a movie theater.

The drama in Japan’s classic Noh theater comes in “the collapse of time, with elements of the past overtaking the present.” That’s a quote from program notes by Yoko Shioya, artistic director of the Japan Society. But in the opening production of her series “Noh-Now!” the present is also taking over the past, with a pair of 14th century Noh plays re-imagined by director Takeshi Kawamura in contemporary settings — a hair salon and a movie theater.

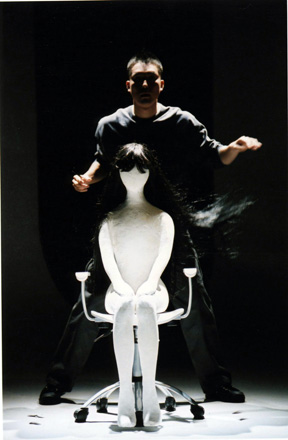

The star of the evening is Akira Kasai, a pioneer of Butoh dance back in the 60s. Cross-dressing in a kimono and a ball gown, he now looks like an ancient Martha Graham, but with the strength and flexibility of a 25-year-old. Kasai plays the title role of a 100-year-old woman in “Komachi,” a remake of the play about a beautiful court poetess who ages into a half-mad crone, living in a hut and wandering the mountains at night. In this incarnation, the old lady is a movie idol from the 30s and 40s, Japan’s “eternal virgin,” now homeless and living in an abandoned movie theater. A down-and-out director of porno movies wanders into the empty cinema, which is still screening Japanese-German propaganda films from the glory days of the Axis. Here the present morphs into the past. The hag and her elderly consort, a furious wrestler-type dressed in a frock coat like Emperor Hirohito, confuse the visitor with her old lover, a film director who died in the war. They try to force him to direct a new movie with the hag as the heroine. In the end she goes completely mad, and after an awesome paroxysm on the floor, strangles the director with loops of 35mm film.

The symbolism seems clear and chilling. The theater is the tomb of Japan’s imperial age, the film is the fantasy that plays on. And the unemployed director, who lists “Horny Housewives” among his few credits, is the drifting Japanese culture, doomed to perish of its own empty consumerism.

This was a riveting production that combined the formalism of Noh theatre with the freestyle madness of Butoh, with movies on two rear screens. The highlight is a long soliloquy by the director-character, delivered in the sing-song wail of Noh tradition, as he paces in front of the screens, while Kasai etches their mutual despair in the air.

This was a riveting production that combined the formalism of Noh theatre with the freestyle madness of Butoh, with movies on two rear screens. The highlight is a long soliloquy by the director-character, delivered in the sing-song wail of Noh tradition, as he paces in front of the screens, while Kasai etches their mutual despair in the air.

The whole three-person cast was masterful. Toru Tezaka as the film director spilled the story in an offhand, cynical tone that still carried a tone of almost-hysterical urgency. And Keiji Fukushi used a slapstick style to make the old man pitiful even in his violence.

“Aoi,” originally a medieval court tale, takes place in an upscale hair salon, where the proprietor is visited by an old mistress jealous of his young new lover. Once again the past invades the present, and the two wind up reliving the murder of her wealthy husband, whom they had chopped up and dissolved with sulfuric acid in a bathtub. This is a star turn for actress Rei Asami, whose past credits include Lady Macbeth, an unmistakable influence in a harrowing scene where she retches while trying to wipe up the last traces of her husband.

Asami’s noir performance as the murderess, complete with cigarette and trench coat, was so deep and finely tuned as to make the rest of the cast look a bit callow. You couldn’t quite believe in her obsession with the aesthetic punk hairdresser.

Under Kawamura’s direction, the whole evening was a refined spectacle of the kind of drama Japanese theater has perfected — sudden shifts of light, claps and clashes of sound, gusts of wind and lightning changes of costume and scenery. The only drawback was the placement of the supertitles, far off to the sides of the stage, so that we non-Japanese speakers repeatedly had to make the painful choice between reading the lines and watching the show.

“Aoi/Komachi” is the first in a spring series of Noh productions, part of Japan Society’s 100th anniversary celebration. It continues in April with a Japanese-directed version of Benjamin Britten’s opera “Curlew River,” based on another classic Noh play.

Photo by Masaru Miyauchi.

Volume 5, No. 12

March 26, 2007

copyright ©2007 by Thomas Phillips

www.danceviewtimes.com