Letter from New York

15

December 2003.

Copyright ©2003 by

Mindy Aloff

Mansaku

Nomura, the John Gielgud of classical Japanese theater, performed with

his son Mansai and his four or five year-old grandson Yuuki at Japan Society

this week in what, for me, was the finest example of the actor’s

art to be seen in New York since January 1982, when I last saw Nomura

at Asia House. Mansaku Nomura is a master of kyogen (“crazy word”)

drama: a six century-old, dialogue-based theater, comic in nature, that

developed contemporaneously with noh and is often performed as an interlude

between tragic or mystical noh plays. In this little season presented

by the Nomura family, the nightly programs of two 45-minute plays were

kyogen all the way—although, the night I attended, one of the two,

Kawakami (translated as Kawakami Headwaters), evoked smiles through

tears, and the other, Utsubozaru (The Monkey Skin Quiver), evoked

laughter through horror. Kawakami is about an elderly blind man

(Mansaku Nomura), who, to regain his sight, must promise to divorce his

beloved wife (played by Yukio Ishida, a former student of Mansaku’s

and now the head of his own noh/kyogen company). Utsubozaru concerns

a samurai (Mansai Nomura) who, about to go hunting, insists on wresting

a trained baby monkey from its trainer in order to skin it for its fur

to cover the quiver for his arrows. The baby monkey, played by Yuuki Nomura,

thinks that the stick being raised to brain it is actually a cue for it

to dance. The samurai, astonished at the monkey’s skill, relents

and keeps his quiver as it was.

Mansaku

Nomura, the John Gielgud of classical Japanese theater, performed with

his son Mansai and his four or five year-old grandson Yuuki at Japan Society

this week in what, for me, was the finest example of the actor’s

art to be seen in New York since January 1982, when I last saw Nomura

at Asia House. Mansaku Nomura is a master of kyogen (“crazy word”)

drama: a six century-old, dialogue-based theater, comic in nature, that

developed contemporaneously with noh and is often performed as an interlude

between tragic or mystical noh plays. In this little season presented

by the Nomura family, the nightly programs of two 45-minute plays were

kyogen all the way—although, the night I attended, one of the two,

Kawakami (translated as Kawakami Headwaters), evoked smiles through

tears, and the other, Utsubozaru (The Monkey Skin Quiver), evoked

laughter through horror. Kawakami is about an elderly blind man

(Mansaku Nomura), who, to regain his sight, must promise to divorce his

beloved wife (played by Yukio Ishida, a former student of Mansaku’s

and now the head of his own noh/kyogen company). Utsubozaru concerns

a samurai (Mansai Nomura) who, about to go hunting, insists on wresting

a trained baby monkey from its trainer in order to skin it for its fur

to cover the quiver for his arrows. The baby monkey, played by Yuuki Nomura,

thinks that the stick being raised to brain it is actually a cue for it

to dance. The samurai, astonished at the monkey’s skill, relents

and keeps his quiver as it was.

Thanks to excellent translations, flashed on a screen, we could easily follow the dialogue, although the physical eloquence of Mansaku and his troupe is of such an order that one could tell what the large emotional changes were through the stage action, alone. Kyogen, as Mansaku has introduced it to the West (which he began to do with his father on a cultural-exchange tour in Paris, in 1957), is a highly physical actors’ theater of extreme elegance and understatement. The body is disciplined to move in such a way that one cannot see how it is propelled, which showcases every slightest change—every facial expression, every gesture, down to the crook of a fingertip. Consequently, every movement pops out and “reads”; and every movement takes on tremendous significance.

Furthermore,

the control that Mansaku exerts over his voice has to be heard to be appreciated.

He can infuse it with rheum or suction it momentarily. He can whisper

to the heavens or shout in a closed chamber, so that one hears it as if

through a wall. In 1982, he reproduced the tolling of bells. Two decades

later, his virtuosity consisted of investing his Eureka! moment of miraculous

sightedness with misery at the prospect of the price he would have to

pay for it, and of addressing a samurai in formal language that slid through

the air on a sea of intangible tears.

Furthermore,

the control that Mansaku exerts over his voice has to be heard to be appreciated.

He can infuse it with rheum or suction it momentarily. He can whisper

to the heavens or shout in a closed chamber, so that one hears it as if

through a wall. In 1982, he reproduced the tolling of bells. Two decades

later, his virtuosity consisted of investing his Eureka! moment of miraculous

sightedness with misery at the prospect of the price he would have to

pay for it, and of addressing a samurai in formal language that slid through

the air on a sea of intangible tears.

Yuuki’s little dance consisted of lighthearted, two-footed hopping and of circling his arm as he held a fan, while his grandfather-as-trainer sang and kept time with the stick fated to be the murder instrument, as he was observed by his handsome father-as-samurai and his father’s go-between servant (Hiroharu Fukata, a perfect wellspring of slowburning exasperation in the course of serving as a live telephone for samurai and trainer). It belongs with the tarentella that Nora dances in A Doll’s House as one of the key allusions in world drama to the idea of dancing as life.

Speaking of A Doll’s House brings me to Mabou Mines Dollhouse, the outrageous, piercing, head-wrenching production adapted and directed by Lee Breuer, for the Mabou Mines troupe, of Ibsen’s play, which has been held over at St. Ann’s Warehouse, in Brooklyn. My freshman lit class at Barnard asked to see it for their final art excursion. Some of them had read Ibsen; some hadn’t, yet that didn’t seem to matter in terms of their response to it. Opinions among them were polemically divided afterwards, and the one who hated it most passionately was the very drama fan who had recommended seeing it in the first place. Perhaps you’ve read about it: the women in the cast are all middling tall to very tall; the men in the cast are all of stunted growth. The set, designed as a “life-sized” doll house, is keyed to the men’s physiques, so that the women must crouch in walking through doors and scrunch up to fit into the furniture, and the men, whom the women sometimes pick up and carry or nurse, become, in effect, their own dolls. There are six dances (or dance-like numbers), choreographed by various individuals; Martha Clarke is also listed as a consultant to the “Tarentella,” which is presented as a nightmare in a nighttime lightning storm, and so is barely visible. A program note by Breuer reads: “Mabou Mines Dollhouse pays homage to an earlier adaptation of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House—Leslie Mohn’s White Bone Demon. Thank you Ms. Mohn for revealing the comedy of 'Bourgeois Tragedy,' the 'surreality' of realism and the politics of deconstruction.”

The

acting, particularly by Maude Mitchell, who plays Nora Helmer as Billie

Burke gone bonkers, is quite absorbing; I’ll never be able to read

or see the play again without thinking of Mark Povinelli, as the deeply

wounded Torvald Helmer, pawing his way up the steps of the audience bleachers

in the dark as he bays for his lost love. The production history of the

play is skewered, but there are whole scenes so unsettling they make the

work seem to have been written five minutes ago. I found an extra dimension

of surprise in certain moments of staging, too, which looked as if they

had sprung, jack-in-the-box fashion, from famous ballets. “It couldn’t

be,” I thought. “That isn’t the set of theater boxes

from Cotillon, or the final moments of Night Shadow,

or the first idea for the ending of Le Baiser de la Fée,

or the Grossvater dance from The Nutcracker. Oh, no! He’s

not going through the canter on the scarf in Nijinsky’s L’Après-midi.

. . .” Still, when Nora, in her lingerie, stands up in one

of the opera house boxes and declares her independence by ripping off

her wig of blonde curls to reveal a “bald” head, she does

look exactly like the doll Coppélia, after Swanilda has revealed

her as a doll instead of a living girl. Coppélia deconstructed?

I walked out thinking about much in the ballet repertory as a feminist

with a very spooky sense of humor and a heat-seeking-missile appreciation

of cruel subtexts might look at it. An interesting world to visit for

an evening, as long as you know your way home.

The

acting, particularly by Maude Mitchell, who plays Nora Helmer as Billie

Burke gone bonkers, is quite absorbing; I’ll never be able to read

or see the play again without thinking of Mark Povinelli, as the deeply

wounded Torvald Helmer, pawing his way up the steps of the audience bleachers

in the dark as he bays for his lost love. The production history of the

play is skewered, but there are whole scenes so unsettling they make the

work seem to have been written five minutes ago. I found an extra dimension

of surprise in certain moments of staging, too, which looked as if they

had sprung, jack-in-the-box fashion, from famous ballets. “It couldn’t

be,” I thought. “That isn’t the set of theater boxes

from Cotillon, or the final moments of Night Shadow,

or the first idea for the ending of Le Baiser de la Fée,

or the Grossvater dance from The Nutcracker. Oh, no! He’s

not going through the canter on the scarf in Nijinsky’s L’Après-midi.

. . .” Still, when Nora, in her lingerie, stands up in one

of the opera house boxes and declares her independence by ripping off

her wig of blonde curls to reveal a “bald” head, she does

look exactly like the doll Coppélia, after Swanilda has revealed

her as a doll instead of a living girl. Coppélia deconstructed?

I walked out thinking about much in the ballet repertory as a feminist

with a very spooky sense of humor and a heat-seeking-missile appreciation

of cruel subtexts might look at it. An interesting world to visit for

an evening, as long as you know your way home.

It was a very happy relief to attend, the next day, a matinee of Francis Patrelle’s Yorkville Nutcracker at the Kaye Playhouse, with its lovely deportment, its gracious dancing (particularly by Jenifer Ringer, with James Fayette, in the Sugar Plum pas de deux), its marvelous snow scene for ballet ice skaters, and its battalions of children, so happy to be on stage making illusions to the best of their ability for family and friends, all for the sake of beauty and love.

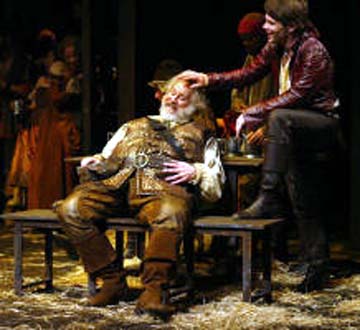

One

word more: There is much to commend in the traditional staging, by Jack

O’Brien, of the adaptation of Shakespeare’s pair of Henry

IV plays, now at the Vivian Beaumont theater in Lincoln Center.

It’s tough, slick and affirmative, like a speech by President Bush.

Indeed, when Prince Hal (Michael Hayden) assumes the ermine and makes

his first address to the assembled with a glittering eye, he resembles

Bush. I was a little sad that the adaptation, by Dakin Matthews (who also

plays Chief Justice Warwick and Owen Glendower), eliminates the closing

words of Part II--an Epilogue, which Shakespeare has "Spoken by a

Dancer" to the audience. ("If my tongue cannot entreat you to

acquit me, will you command me to use my legs? And yet that were but light

payment, to dance out of your debt.") However, I'm glad to report

that the deathbed advice of Henry IV to his namesake, on the verge of

becoming Henry V, includes those immortal lines, "Therefore, my Harry,

/ Be it thy course to busy giddy minds / With foreign quarrels; that action,

hence borne out, / May waste the memory of the former days." Dana

Ivey’s Dana Ivey's Mistress Quickly and Audra McDonald’s Lady

Percy are larger-than-life creations. As for Kevin Kline’s Falstaff:

Whoa! Heartthrob in a fat suit! The ominously efficient stage mechanisms

of Ralph Funicello's tower-and-tunnel set are full of their own surprising

choreography, and the momentary vistas into deep, dark space they provide

are what Shakespeare's histories are all about—Mindy Aloff

One

word more: There is much to commend in the traditional staging, by Jack

O’Brien, of the adaptation of Shakespeare’s pair of Henry

IV plays, now at the Vivian Beaumont theater in Lincoln Center.

It’s tough, slick and affirmative, like a speech by President Bush.

Indeed, when Prince Hal (Michael Hayden) assumes the ermine and makes

his first address to the assembled with a glittering eye, he resembles

Bush. I was a little sad that the adaptation, by Dakin Matthews (who also

plays Chief Justice Warwick and Owen Glendower), eliminates the closing

words of Part II--an Epilogue, which Shakespeare has "Spoken by a

Dancer" to the audience. ("If my tongue cannot entreat you to

acquit me, will you command me to use my legs? And yet that were but light

payment, to dance out of your debt.") However, I'm glad to report

that the deathbed advice of Henry IV to his namesake, on the verge of

becoming Henry V, includes those immortal lines, "Therefore, my Harry,

/ Be it thy course to busy giddy minds / With foreign quarrels; that action,

hence borne out, / May waste the memory of the former days." Dana

Ivey’s Dana Ivey's Mistress Quickly and Audra McDonald’s Lady

Percy are larger-than-life creations. As for Kevin Kline’s Falstaff:

Whoa! Heartthrob in a fat suit! The ominously efficient stage mechanisms

of Ralph Funicello's tower-and-tunnel set are full of their own surprising

choreography, and the momentary vistas into deep, dark space they provide

are what Shakespeare's histories are all about—Mindy Aloff

Photos:

First: A younger Mansaku Nomura as the Blind Husband in Kawakami

Headwaters

Photographer unknown.

Second: Mansai Nomura as the Lord (right) and Yuuki Nomura as the

Monkey in The Monkey Skin Quiver Photographer unknown.

Third: Maude Mitchell as Nora Helmer and Mark Povinelli as Torvald

Helmer in Mabou Mines Dollhouse.

Photo: Jay Muhlin.

Fourth: Kevin Kline as Falstaff and Michael Hayden as Prince Hal in

Henry IV.

Photo: Paul Kolnik.

Casting:

Mansaku-no-Kai

Kyogen Company

By Mansaku & Mansai Nomura

10-12 December 2003

Japan Society

10, 12 December

Kawakami Headwaters (Kawakami)

Blind Husband: Mansaku Nomura

Wife: Yukio Ishida

Koken (stage attendant): Kazunori Takano (10), Haruo Tsukizaki (12)

The Monkey

Skin Quiver (Utsubozaru)

Lord: Mansai Nomura

Taro-kaja: Hiroharu Fukata

Monkey Trainer: Mansaku Nomura (10), Yukio Ishida (12)

Monkey: Yuuki Nomura

Jiutai (chorus): Yukio Ishida, Kazunori Takano (10 only)

Koken: Haruo Tsukizaki (10), Kazunori Takano (12)

11 December

Sweet Poison (Busu)

Taro-kaja: Yukio Ishida

Master: Haruo Tsukizaki

Jiro-kaja: Hiroharu Fukata

Koken: Kazunori Takano

The Monkey

Skin Quiver

Lord: Mansaku Nomura

Taro-kaja: Kazunori Takano

Monkey Trainer: Mansai Nomura

Monkey: Yuuki Nomura

Koken: Hiroharu Fukata

Mabou

Mines Dollhouse

Through 14 December 2003

St. Ann’s Warehouse (Brooklyn)

Produced for Mabou Mines by Lisa Harris,

in association with Dovetail Productions, with the participation of Robert

Blacker

Direction

and Adaptation (from Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House,

with snippets from Ibsen’s The Vikings of Helgeland): Lee

Breuer

Music: Eve Beglarian

Piano score: adapted from Edvard Grieg

“Du grønne glitrende tre”: traditional

“Dollhouse Opera Finale”: Eve Beglarian

Set: Narelle Sissons

Lighting: Mary Louise Geiger

Costumes: Meganne George

Puppetry: Jane Catherine Shaw

Sound: Edward Cosla

Choreography:

“Blackmail” (Nora & Krogstadt, Act I): Eamonn Farrell

“The Minuet” (Act II): Norman Snow

“The Tarentella” (Act II): Martha Clarke (choreographic consultant),

assisted

by Gabrielle Malone

“Kristine’s Dream” (Act III): Clove Galilee

“The Seduction” (Kristine & Krogstadt, Act III): Erik

Liberman

Puppet choreography (Act III): Jane Catherine Shaw

Dramaturgy: Maude Mitchell & Jocelyn Clarke

Dialect Consultant: Aase Holby

Critical Scholarship: Anne-Charlotte Harvey

Cast:

Actors: Maude Mitchell (Nora Helmer), Mark Povinelli (Torvald Helmer),

Kristopher Medina (Nils Krogstadt), Honora Fergusson (Kristine Linde),

Ricardo Gil (Dr. Rank), Margaret Lancaster (Helene, originally performed

by Lisa Harris), Ning Yu (The Pianist), Tate Katie Mitchell (Emmy Helmer),

Zachary Houppert Nunns & Matthew Forker (Ivar Helmer), Sophie Forker

(Dream Figure)

Lead Opera House Singers: Lauren Skuce (soprano), Peter Stewart (baritone)

Doll Chorus Singers: Eve Beglarian, Nick Brooke, Milan Cronovich, Corey

Dargel, Ellie Everdell, Clove Galilee, Mikki Jordan, Michael Miller, Peter

Previti, Suanne Radar, Jenny Rappo, Jared Stein

Snare Drum on Anthem: Mary Fodiguez

Puppeteers: Jane Catherine Shaw, Rachel Applebaum, Gwen Ossenfort, Eva

Lansberry, Kristopher Medina, Honora Fergusson, Ilia Dodd Loomis, Lisa

Harris

Henry

IV

by William Shakespeare

Lincoln Center Theater at the Vivian Beaumont

Direction: Jack O’Brien

Adaptation (Pts. I & II): Dakin Matthews

Sets: Ralph Funicello

Costumes: Jess Goldstein

Lighting: Brian MacDevitt

Original Music & Sound: Mark Bennett

Fight Director: Steve Rankin

Special Effects: Gregory Meeh

Cast:

Richard Easton (King Henry IV), Michael Hayden (Henry [“Hal”],

Prince of Wales),

Lorenzo Pisoni (John of Lancaster), Dakin Matthews (Chief Justice Warwick,

Owen Glendower), Tyrees Allen (Earl of Westmoreland), Byron Jennings (Thomas

Percy, Earl of Worcester), Terry Beaver (Earl of Northumberland), Dana

Ivey (Lady Northumberland, Mistress Quickly), Ethan Hawke (Henry Percy

[“Hotspur”]), Audra McDonald (Lady Percy), Peter Jay Fernandez

(Sir Richard Vernon), Scott Ferrara (Edmund Mortimer), Anastasia Barzee

(Lady Mortimer), Stevie Ray Dallimore (Lord Hastings), Tom Bloom (Archbishop

of York, Justice Silence), C.J. Wilson (Earl of Douglas), Kevin Kline

(Sir John Falstaff), Steve Rankin (Poins), David Manis (Pistol), Ty Jones

(Nym), Stephen DeRosa (Bardolph), Genevieve Elam (Doll Tearsheet), Aaron

Krohn (Francis), Jed Orlemann (Ralph, Davy), Jeff Weiss (Justice Shallow).

Also: Christine Marie Brown, Albert Jones, Lucas Caleb Rooney, Daniel

Stewart Sherman, Corey Stoll, Baylen Thomas, Nance Williamson, Richard

Ziman (Soldiers, Servants, Tavern People, Squires).

Originally

published:

www.danceviewtimes.com

Volume 1, Number 12

December 15, 2003

Copyright ©2003 by Mndy Aloff

|

|