A Veteran and a Raw Talent

The

Sleeping Beauty

New York City Ballet

New York State Theater

February 24,

28, 2004

by

Mindy Aloff

copyright

2004 by Mindy Aloff

published 1 March 2004

This

week, reviewing NYCB’s production of The Sleeping Beauty

on his Saturday WQXR-FM radio spot (6 p.m.), Francis Mason observed that

when Margot Fonteyn took New York by storm with her Aurora in The Royal

Ballet’s production at the Old Met in 1949, she had already been

dancing the role for ten years. It’s a point well taken. As Boris

Lermontov observes in The Red Shoes, one cannot produce a rabbit

from a hat if there is not already a rabbit in the hat. On the

other hand, Ninette de Valois was producing an Aurora who, by a number

of accounts, had the right sensibility and temperament for the role from

the beginning.

This

week, reviewing NYCB’s production of The Sleeping Beauty

on his Saturday WQXR-FM radio spot (6 p.m.), Francis Mason observed that

when Margot Fonteyn took New York by storm with her Aurora in The Royal

Ballet’s production at the Old Met in 1949, she had already been

dancing the role for ten years. It’s a point well taken. As Boris

Lermontov observes in The Red Shoes, one cannot produce a rabbit

from a hat if there is not already a rabbit in the hat. On the

other hand, Ninette de Valois was producing an Aurora who, by a number

of accounts, had the right sensibility and temperament for the role from

the beginning.

Not all great dancers are great Auroras. The role requires tremendous dance ability and stamina, of course—the ballerina is in the spotlight, carrying the banner for classicism, for over half the evening—but it also requires a sense of decorum, musical wisdom, and a certain kind of dulcet approach to any human interchange that, in 2004, isn’t valued in society at large and must be reinvented for the stage. If the 16 year-old Aurora that Petipa invented and that Fonteyn danced were to apply to a sorority today, she’d either be dismissed as a joke or submitted to a terrible hazing as a stupe. Although she has energy and temperament to spare, she is what used to be called an innocent, a term that has been subjected to such ferocious deconstruction in the past quarter century that I’m amazed I remembered it at all. Now, there are many wonderful ways to be 16 off stage, and innocence is not necessary to the wonderfulness there, as long as other humane qualities are in place, such as generosity and curiosity and, in the right situation, humility. But on stage, in this role in this ballet, innocence is indispensable.

A big part of the projection of innocence is a factor over which dancers have little control: how they look—their height, their bone structure, their musculature, even the spacing of their eyes. (Although Aurora is ultimately a performer’s construction, or reconstruction, over several hours, widely spaced eyes help to convey instantly the childlike quality that makes this antiquated teenager lovable.) Auroras tend to be small, and for a theatrical reason: the supernatural forces that argue over the character’s destiny—Carabosse and The Lilac Fairy—have to read as larger, supernatural forces. Great exceptions are exceptions; the easiest way to cast all of these roles, once the question of sufficient technique and strength is resolved, is according to body type. But there is another aspect to Aurora over which the dancer does have some control: the display of her temperament in performance. For some Auroras the projection of sweetness—which is a theatrical matter, different from whether the person dancing is actually a lamb—will be a product of the dancer more or less being herself on stage; for others it will mean acting. It doesn’t matter which route one takes, as long as one gets there.

I have been an admirer of Ashley Bouder’s virtuosity from the time she danced the lead in Stars and Stripes at the annual Workshop of the School of American Ballet. A season or two ago, I saw her in the title role of Firebird, coached, I was told, by Merrill Ashley, herself. Bouder was brilliant, both in her movement quality and in her characterization. However, she was also slightly robotic in places: she had the look of someone who had been coached. She hadn’t yet been able to absorb the lessons, to make the role her own. That quality also marred the first half of her performance as Aurora. When she took that terrifyingly exposing series of piqué arabesques, holding each pose while she lowered her standing foot from full point to flat sole, then converted the arabesque to allongée, then glanced back at the little page she had just passed; or when she took each suitor’s rose, smelled it or held it up, and then took a pirouette; or when she rushed the bouquet over to the Queen and, in a moment of exuberance, tossed them in her lap, she looked as if she were counting. She didn’t look in the moment. She didn’t look as if the actions were coming from someplace spontaneous but rather someplace calculated.

Aurora has to perform several difficult dance actions four times, to acknowledge each of her four suitors; Bouder performed each acknowledgement exactly the same way, which rendered the suitors anonymous and made her Aurora look preoccupied. It is this, more than the unfortunate moment when she had to come off point during one of the iconic balances in the Rose Adagio (those balances would make anyone be preoccupied; the point is not to look it), that worried me, not only about this able, potentially marvelous dancer but also about the way she was being prepared by the company to assume this role. In the second half, after the intermission, when Aurora is able to dance with Prince Désiré—at this performance, Damian Woetzel, at his most winning—Bouder seized the moment and turned in some extraordinary dancing: hugely scaled, scintillating, assured. It was in the second half that I began to understand why she had been cast. Alas, what makes Beauty great is both its halves; I hope very much that Bouder will have more chances in it, and that she and an advisor will be able to think about her approach to the Rose Adagio.

Miranda Weese, later in the week, is a veteran Aurora, and it was watching her that I felt the force of Mason’s point about the importance of having experience in the role. She knew how to pace herself; she had worked out the differences among her presentation of self as Aurora in the Rose Adagio, the Vision scene, and the Wedding. She treated everyone, beginning with her Prince—Philip Neal, dancing with more fire on this occasion than I’ve seen from him in a while—with a royal grace as if to the manner born. Indeed, she was a little too restrained in her manner sometimes: if Aurora is in a state of happy excitement on her 16th birthday, and has just happily gotten through some very difficult dancing with dash and brio, it is a little alarming to see her present the suitors’ roses to her mother in a studiously neat bundle, laid with overweening care at the Queen’s feet. What sort of childhood did the character have that she would be robbed of just a little careless elation? Still, there were passages of gorgeous dancing in this performance, especially when it came to pirouettes and renversé movements, which Weese suspended and held with considerable aplomb. Physically, she looks a little too sophisticated for the role; however, her analysis of it and her understanding of its accents and options were visible in her performance.

I was a little disappointed to find that the three Auroras I saw this season all had to look down at their feet when they descended the stairs on their entrances for the Rose Adagio.

The two Carabosses—Merrill Ashley (in Weese’s performance) and Kyra Nicholas (in Bouder’s)—were thrilling. Ashley, in particular, varied her tone over the course of her imprecations at the Christening, passing from fury to sardonic exaggeration of pomp and circumstance, to silent, chilling hilarity. Of course, she, too, has had years to think about her approach. (Nichols was making her debut as Carabosse this season.)

Maria Kowroski must be one of the most magesterial Lilac Fairies in history: remote, untouchable, quietly commanding, a creature of another world. She dances Lilac the way she dances “Diamonds” in Jewels, but here the approach is apt. Amanda Hankes, a member of the corps de ballet making her debut as Lilac (with Weese and Ashley), looked lovely, although her dancing was a little stolid. At both performances, the Garland Waltz was a dream, and all the SAB students elsewhere in the ballet were coached to perfection. (Gabrielle Whittle, who coaches these children, deserves a special medal of honor.) Andre Kramarevsky, the hapless factotum, Catalabutte, at both performances, approaches the character very broadly; however, I was very grateful to him for his absolute assurance in every gesture.

Among the other Fairies, I’d like to single out the individual and specific achievements of Dena Abergel (Tenderness), Jessica Flynn (Vivacity), and, most especially, Carrie Lee Riggins (also Vivacity) and Rachel Rutherford (Generosity). Their Cavaliers—Jerome Johnson, Amar Ramasar, Henry Seth, Jonathan Stafford, Sean Suozzi, and Andrew Veyette at both performances—turned in fine dancing both times.

The conductor at Bouder’s performance was Andrea Quinn. The overture she pulled together was especially nice and the orchestra sounded rehearsed during much of the rest of the night, although the music for the Wedding pas de deux also sounded a little zoned-out. During Weese’s performance, the orchestra under Maurice Kaplow’s baton seemed almost to be pulled apart during the Panorama, and the horn section was just sour. Why? Why? Why? Terry Teachout has charged the New York City Ballet orchestra with being “the worst” orchestra in New York. I don’t think he’s attended some of the musical concerts I have, but it’s true that one grieves to hear this glorious musical repertory played as if the musicians were also banking on line at the same time.

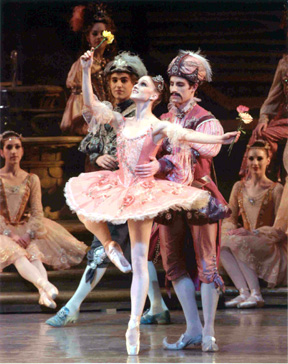

Photo: Ashley Bouder with Arch Higgins in the Rose Adagio from Peter Martins production of The Sleeping Beauty. Photo by Paul Kolnik.

Reviews of other Winter Season performances:

Some

thoughts on Balanchine, with references to Arlene Croce (Gay Morris)

Prodigals, Gods, and Music:

"Heritage" Week 1 at New York City Ballet (Susan Reiter)

Harlequinade

(Nancy Dalva)

Tschaikovsky Piano Concerto

No. 2/Harlequinade (Mary Cargill)

Double Feature

(Mary Cargill)

The Show Goes On: Donizetti

Variations/Scotch Symphony/Tschaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2

(Mary Cargill)

Designs that Pack a Punch:

Jewels (Susan Reiter)

Swanilda's

World (Mary Cargill)

New Casts in Jewels

(Mary Cargill)

A Valiant Beauty (Mindy

Aloff)

Also Mindy Aloff's Letters related to the Balanchine Celebration:

Letter

14 (Balanchine Celebration; Times Talk)

Letter 15 (Midsummer

Night's Dream)

Letter 16 (Double Feature)

Letter 17 (Barefoot Balanchine

at Sarah Lawrence)

Originally

published:

www.danceviewtimes.com

Volume 2, Number 9

March 1, 2004

Copyright

© 2004 by Mindy Aloff

|

|