Eve of Destruction

Akram

Khan, Kaash

Yerba Buena Theater, San Francisco

September 18, 2003

By

Paul Parish

Copyright

©2003 by Paul Parish

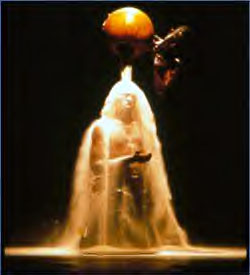

Akram Khan's brilliant Kaash began before I was aware of it. The house lights were still up; I was turned around talking to the person behind me when I realized I'd lost her attention—a look of alarm had come into her eyes, and I turned to see there was a knife-blade slender youth onstage, with his back to us, dressed in black, gazing motionless into the huge black rectangle suspended, floating on the horizon in silence like a monstrous new planet or a black sun up in the sky. The scene looked like a Rothko—and the image on the back wall did not change throughout the disturbing, rattling contemporary dance that took place in front of it for the next ninety minutes or so. The black hopeless object held focus amidst peripheral washes of color, sometimes pearly white, sometimes blood-red. The entire dance seemed to be the image of an unquiet train of thought that began with "If..." (Khaash means "if," or alternatively "what if," in Hindi, according to a program note) and went to a lot of dark places...... One of those dark meditations that leads you in an apparent circle but in fact is spiraling downwards. When we reached a bleak place after about an hour, and were overtaken by an overwhelming roar that shook me to the bones, it turned out that the dance had returned to the opening configuration, and the opening section began all over again.

After a long, ominous spell, the youth (who stood off-center left) was joined by a line of dancers perpendicular to us, 4 of them. But as tremendous percussion broke out, in a rhythm based on sevens, when suddenly the dancers began to lunge each on their own counts, it seemed like many more than that.

Seven is, to most Americans, a very upsetting rhythm—the effect is like minding a washing machine which is off-balance but not so badly off that it actually comes to a halt. Bad enough to set your teeth on edge, make your head ache. (The only place where the audience broke out into spontaneous applause was in the third section, which was virtuosically syncopated but was based on 8s and close enough to hip-hop for everybody to be deeply comfortable with it).

Indeed, seven may be a disturbing rhythm most everywhere. In medieval numerology, 7 is the number of bad news—mutability"—the world of loss, deception, decay, while 8 is the number of eternity (an 8 on its side is still the symbol for infinity.) The unfinished book Seven of Spenser's great romance The Faerie Queene is represented only by the disturbing "Mutabilitie Cantos."

The desolate adagio began with a reference to Radha. The Bay Area has a large Indian community, so I know just enough about Indian culture—from the performances of the excellent Chitresh Das and Purnima Jha, who live and teach and perform here, and from seeing Peter Brook's Mahabharata on PBS (which led me to read the book) to recognize the hand-gesture with which this lonely dance began. Two people stand up stage in intimate rapport, while a woman downstage unwinds her arm with difficulty from behind her—as if an invisible jailer has trapped her arm behind her and slowly lets her free. Her hand is making the mudra for Radha—the thumb and forefinger touch (as when you make bird-shadows play on the wall). It is the image of a dove, and represents Radha, Krishna's beloved. The dance which follows—slow, troubled rolling on the floor like someone who can't sleep—seems to be a version of a theme from Indian mystic poetry, Radha's longing for the god who does not come to her. She waits and suffers and he does not come. The company has five dancers—the "youth" and two very slender females, plus an older pair, with rounder, softer bodies: Khan himself, and the woman who did this solo, who has a tenderness and emotional depth I saw nowhere else that night.

There is no need to assert that this movement is "about" Radha. It is a universal theme—Rumi uses similar imagery, as do the mystics in dealing with the "dark night of the soul." Mark Morris used a similar motif—the solitary whose sufferings are not seen by happy couples—in Going Away Party, which played in Zellerbach Hall only a couple of weeks ago.

Khan's movement idiom itself does not much look like Kathak.. It looks more like Laban's Schwungung—the swinging movements of early German modern dance —than it does the Kathak which advance press had led me to expect. Certainly Khan has studied Kathak, and he's said that his style is 80 percent Kathak, but that must be in its rhythmic and percussive core, the germ of the phrase-making and disposition of the trajectories—for the geometry looks very much like lunging, fall and recovery, and release work; the larger designs are often contrapuntal. I noticed some Kathak chainés, but none of the footwork I was expecting. The arms are wonderful.

Khan came here with dazzling notices from London, where he lives—his family stems from Bangla Desh, but he is the heir of all the ages and of all cultures. He seems to have no axe to grind about imperialism, alluding freely and effortlessly to high and low and pop cultures with casual sophistication. It's not an accident that the title of this piece ("Khaash"—if in Hindi) echoes the best-known poem of Rudyard Kipling ("If"), the most critical if also the most popular poet of the British Empire. (Indeed, Khan's first theatrical breakthrough came in a version of Kipling's Mowgli stories.) And yet it makes no difference at all whether or not you hear the pun.

Figninto

Salia ni Seydou

Yerba Buena Center for the Arts Theater

September 19, 2003

Kaash was the antepenultimate in a brief, brilliant series, the San Francisco International Arts Festival, which it is hoped will be the seed of a festival which will grow next year and eventually become something on the order of Edinburgh's. It's a tall order, but they got off to a marvelous beginning with Tere O'Connor and closed with three performances on the weekend by San Francisco's own Circo Zero (by which time I was exhausted and didn't make it.)

But

I did see Friday night's performance, another remarkable concert, the

first Bay Area appearance by the West African company Salia ni Seydou

(directed by Salia Sanou and Seydou Boro) from Burkina Faso, West Africa.

The

Piece is called Figninto, which means "he who does not see,

a blind man." Unfortunately,

I can not claim to have had insight into the choreography. It was said

to be about spiritual blindness, and I believe it—the performances

were not only virtuosic in the extreme, they were brave, committed at

a level one rarely sees.

But

I did see Friday night's performance, another remarkable concert, the

first Bay Area appearance by the West African company Salia ni Seydou

(directed by Salia Sanou and Seydou Boro) from Burkina Faso, West Africa.

The

Piece is called Figninto, which means "he who does not see,

a blind man." Unfortunately,

I can not claim to have had insight into the choreography. It was said

to be about spiritual blindness, and I believe it—the performances

were not only virtuosic in the extreme, they were brave, committed at

a level one rarely sees.

The choreographers have taken traditional African movement—the rib isolations, the extraordinary articulation of the shoulders and arms are particularly memorable—but left traditional choreographic methods behind. Indeed, the movement phrases felt very close to Butoh at times, as did the staging, which involved pouring sand over the dancers' bodies and climaxed at the end in a coup de theatre when one of the antagonists emptied an entire calabash full of fine grit over the head of another.

There was intense nervous energy in the portrayals. It's an unusual combination to see in a dancer with such an athletic body such levels of spiritual agitation. The company consisted of a drummer and a flautist and three male dancers, all of them uncommonly legible and fascinating to look at.

I could not fathom it but the performances were thrilling, and their articulation was second to none. The dancers were Seydo Boro, Ousseni Sako, and Salia Sanou, the musicians Dramane Diabate (percussion) and Irisso Tao.

This performance was a benefit for the family of Malonga Casquelourde, a very important Congolese choreographer/ teacher who had lived in the Bay Area since the early 70's and was killed in a tragic car accident this past June. Indeed the entire festival was dedicated to his memory, and an altar had been set up in the lobby of the Yerba Buena Theater and been maintained afresh for the three week run of the festival. Casquelourde's positive influence in the community can not be overstated. He had taught at Stanford and SF State universities, civil servants at City Hall have taken his classes, I myself have taken his classes. His work in the ghettoes was important, but his extension of the riches of African dance to the entire Bay Area community has been an immeasurable force for good.

Photo

credits:

First: Alan Parker

Second: Chris Nash

Third and fourth photo: no information was available

Originally published:

www.danceviewtimes.com

Volume 1, Number 1

September 29, 2003

Copyright ©2003 by Paul Parish

|

|

|