Silken Illusions

15th

Anniversary Performance

Lili Cai Chinese Dance Company

Yerba Buena Center for the Arts Theater

San Francisco, California

November 15, 2003

by

Paul Parish

copyright © 2003 by Paul Parish

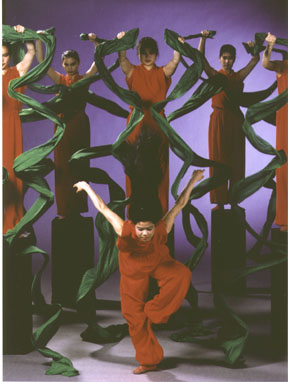

The

most interesting part of the Lili Cai Chinese Dance Company's fifteenth

anniversary show last Saturday night was the series of stunning clips

in the video retrospective, which was screened just before the intermission.

The marvelous deep, high stage of the theater at the Yerba Buena Center

for the Arts downtown had just been filled with the snaking whorls of

traditional Chinese ribbon dancing, beautifully lit, which at moments

caught me up in complete fascination, watching the gorgeous silk reveal

the inner secrets of turbulent currents, but then left me wool-gathering,

reflecting (for example) on the possible debt of Loie Fuller to this form

of Chinese dancing. The three dances performed that evening were too similar.

In all of them, the dancers were there to make other things dance—you

followed the movements of cloth, or of flames, not the bodies of the dancers.

Which that night, for me, let me drift off into thought. But the clips

in the video arrested me, held me tight, impressed me repeatedly with

how strong the company is, how varied their repertory, how open they are

to new influences and how successful they are in collaborating with artists

from other cultures. I found myself wishing they were performing at least

one dance that was more rhythmic and embodied, like their award-winning

Common Ground (which they co-created with the African-heritage

Dimensions Dance Theater) and is strong, earthy, and grounded.

The

most interesting part of the Lili Cai Chinese Dance Company's fifteenth

anniversary show last Saturday night was the series of stunning clips

in the video retrospective, which was screened just before the intermission.

The marvelous deep, high stage of the theater at the Yerba Buena Center

for the Arts downtown had just been filled with the snaking whorls of

traditional Chinese ribbon dancing, beautifully lit, which at moments

caught me up in complete fascination, watching the gorgeous silk reveal

the inner secrets of turbulent currents, but then left me wool-gathering,

reflecting (for example) on the possible debt of Loie Fuller to this form

of Chinese dancing. The three dances performed that evening were too similar.

In all of them, the dancers were there to make other things dance—you

followed the movements of cloth, or of flames, not the bodies of the dancers.

Which that night, for me, let me drift off into thought. But the clips

in the video arrested me, held me tight, impressed me repeatedly with

how strong the company is, how varied their repertory, how open they are

to new influences and how successful they are in collaborating with artists

from other cultures. I found myself wishing they were performing at least

one dance that was more rhythmic and embodied, like their award-winning

Common Ground (which they co-created with the African-heritage

Dimensions Dance Theater) and is strong, earthy, and grounded.

The video made clear just how much Lili Cai's work is a spectacle. When they opened for the Grateful Dead a few years back, the crowd at the Colisseum went wild when they did their hundred-armed Buddha effect, it was the image that did it. The effect is a traditional Chinese dance-theater optical illusion, created by lining all the dancers up perpendicular to the audience and having them open their arms in an elaborate sequence—which may look even better on video than in 3-D, because it is designed to create a mythic pattern in two dimensions, like a painting. Similarly, many of the ribbon dances look in some ways MORE stunning in two dimensions than in three, like calligraphy of the utmost fantasy--and certainly the video collaboration they did with Ed Tennenbaum, who let the trajectories of the ribbons lay down tracks one upon another on his screen, looks like a new form of action painting—on-going marbling. It was a light show that did not stop being fascinating.

Cai,

who came to San Francisco from Shanghai, where she was a principal dancer

with the Shanghai Opera House, came to the Bay Are twenty years ago and

quickly set about teaching and making contemporary dances using traditional

Chinese materials. The civilization of China is an ancient one, of course.

It embraces many cultures, has gone through many stages, and has survived

and assimilated the cultures of conquerors and the conquered. It's humbling

for an outsider like me to begin to imagine how ignorant I am of what

goes into this art. One thing that seems to pervade Chinese art, though,

is a fascination with the beauty of that which vanishes. The beauty of

the ribbon dances is both philosophical and sensuous—you see the

consequences of very small movements (made by the dancers' hands) as they

are played out in the yards and yards of silk that have been set in motion

and are being pulled through serpentine paths—it's like being able

to see the wind, or the passage of time itself, watching the silk whorl

and ripple and curl back on itself, all going by so fast you can't be

sure what you saw. In the interstices of the movement, I found myself

reflecting on the Chinese fascination with fireworks—which is also

a vanishing act that takes place in the air, in the dark—and with

gambling, the manifold unknowable unforeseeable permutations that can

come from a single initiative.

Cai,

who came to San Francisco from Shanghai, where she was a principal dancer

with the Shanghai Opera House, came to the Bay Are twenty years ago and

quickly set about teaching and making contemporary dances using traditional

Chinese materials. The civilization of China is an ancient one, of course.

It embraces many cultures, has gone through many stages, and has survived

and assimilated the cultures of conquerors and the conquered. It's humbling

for an outsider like me to begin to imagine how ignorant I am of what

goes into this art. One thing that seems to pervade Chinese art, though,

is a fascination with the beauty of that which vanishes. The beauty of

the ribbon dances is both philosophical and sensuous—you see the

consequences of very small movements (made by the dancers' hands) as they

are played out in the yards and yards of silk that have been set in motion

and are being pulled through serpentine paths—it's like being able

to see the wind, or the passage of time itself, watching the silk whorl

and ripple and curl back on itself, all going by so fast you can't be

sure what you saw. In the interstices of the movement, I found myself

reflecting on the Chinese fascination with fireworks—which is also

a vanishing act that takes place in the air, in the dark—and with

gambling, the manifold unknowable unforeseeable permutations that can

come from a single initiative.

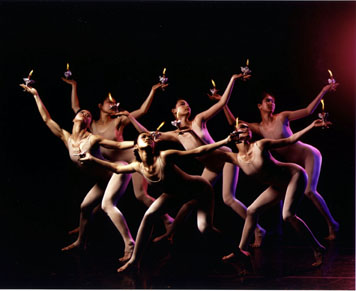

Candelas,

an adagio for five women in flesh-colored unitards carrying a candle in

each hand, opened the second half. What a relief it is to see a culture

where feminism has not made women self-conscious about seduction. Candelas

looks to me—admittedly, very much an outsider—like an outgrowth

of the dance of concubines: it is a high-minded, even sublime setting

of the Adagietto from Mahler's Fifth Symphony, the best dance setting

I have ever seen to that music (and there have been many). What makes

it work for me is the basis of the movement in an erotic mode of contortion.

The dancers reach behind themselves (holding candles, remember)-- investigating

the possibilities of rotation in the spine, the shoulder and elbow, that

will allow them to move these flames in figures of eight with maximum

amplitude and grace. The difficulty is the measure of its generosity.

The silhouette in this dance looks astonishingly African; the pelvis is

marvellously atilt, the lumbar arch is pronounced, the arms serpentine,

the knees almost always bent, sometimes all the way to the floor. The

ballerina repeatedly does a fondu all the way down on the right foot,

with the left extended in tendu, as she reaches forward in the breast,

all the while bearing a living flame in slow wreathing circles. At the

last great climax in the music, the candles suddenly configure in a huge

oval that reminds me of Tantric images of the Buddha, and reminds me that

the Tantric path ("the road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom"

is a line from Blake, but it encapsulates Tantric thought) is the high

erotic mode, with much in common with Rumi, The Song of Songs, and indeed,

the Fifth Symphony of Mahler.

Candelas,

an adagio for five women in flesh-colored unitards carrying a candle in

each hand, opened the second half. What a relief it is to see a culture

where feminism has not made women self-conscious about seduction. Candelas

looks to me—admittedly, very much an outsider—like an outgrowth

of the dance of concubines: it is a high-minded, even sublime setting

of the Adagietto from Mahler's Fifth Symphony, the best dance setting

I have ever seen to that music (and there have been many). What makes

it work for me is the basis of the movement in an erotic mode of contortion.

The dancers reach behind themselves (holding candles, remember)-- investigating

the possibilities of rotation in the spine, the shoulder and elbow, that

will allow them to move these flames in figures of eight with maximum

amplitude and grace. The difficulty is the measure of its generosity.

The silhouette in this dance looks astonishingly African; the pelvis is

marvellously atilt, the lumbar arch is pronounced, the arms serpentine,

the knees almost always bent, sometimes all the way to the floor. The

ballerina repeatedly does a fondu all the way down on the right foot,

with the left extended in tendu, as she reaches forward in the breast,

all the while bearing a living flame in slow wreathing circles. At the

last great climax in the music, the candles suddenly configure in a huge

oval that reminds me of Tantric images of the Buddha, and reminds me that

the Tantric path ("the road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom"

is a line from Blake, but it encapsulates Tantric thought) is the high

erotic mode, with much in common with Rumi, The Song of Songs, and indeed,

the Fifth Symphony of Mahler.

The

evening's premiere, Si Ji ("the Four Seasons"), is

a veil dance: each of the dancers is covered with a good ten yards of

sheer silk organza, which they poke and poke and poke and poke and jump

about inside, causing the stuff to do what you'd expect. BEAUTIFUL stuff,

beautifully lit (by Clyde Sheets) in colors designed to suggest the changing

seasons. The dance could not hold my attention, despite its arresting

score, composed for the occasion by company's co-founder, Gang Situ, and

brilliantly played by the solo cellist, Robin Bonnell. Again, I found

my mind wandering: the last section, which the dancers performed with

the organza tied around their bodies under the breast, brought back such

stunning memories of Balanchine's Bugaku (where the ballerina

performs pirouettes and other movements of grand adagio while swathed

in an awful lot of very similar cloth), made me wonder if this is an ancient

genre in China which the Japanese adopted into Gagaku and Balanchine incorporated

into his piece.

The

evening's premiere, Si Ji ("the Four Seasons"), is

a veil dance: each of the dancers is covered with a good ten yards of

sheer silk organza, which they poke and poke and poke and poke and jump

about inside, causing the stuff to do what you'd expect. BEAUTIFUL stuff,

beautifully lit (by Clyde Sheets) in colors designed to suggest the changing

seasons. The dance could not hold my attention, despite its arresting

score, composed for the occasion by company's co-founder, Gang Situ, and

brilliantly played by the solo cellist, Robin Bonnell. Again, I found

my mind wandering: the last section, which the dancers performed with

the organza tied around their bodies under the breast, brought back such

stunning memories of Balanchine's Bugaku (where the ballerina

performs pirouettes and other movements of grand adagio while swathed

in an awful lot of very similar cloth), made me wonder if this is an ancient

genre in China which the Japanese adopted into Gagaku and Balanchine incorporated

into his piece.

So they look like jellyfish, or like chicks about to hatch, or silk-worms struggling to be born. Or like Wilis preparing to dance. Except that none of these made much impact on me, and the idea of the four seasons would never have occurred to me if I had not read about it. What I missed most was a sense of rhythm, trajectory, and ballon in the allegro, which to me seemed choppy and frantic rather than airborne and natural (which I presume is the intention, but I admit that is a LARGE presumption). I'm not blaming the dancers for not providing these qualities. Perhaps, on another night, I would have been able to do without them. The dancers are lovely and certainly jump well—they are all beautifully trained, finely disciplined theater artists. Their names are Yan Hai, Quiong Huang, Tammy Li, Ada Liu, Chih-Ting Shih, and Phong Voong.

Photos:

First:

Begin from here.

Second: Strings Calligraphy

Third:

Candelas.

Fourth: Si Ji

Photo credit: Marty Sohl

To learn more about the Lily Cai Chinese Dance Company. Visit www.ccpsf.org

Originally published:

www.danceviewtimes.com

Volume 1, Number 9

November 24, 2003

Copyright ©2003 by Paul Parish

|

|

|