After Revelations

Heart

Beat, Juba, Treading

Alvin Ailey American

Dance Company

[Presented by Cal Performances]

Zellerbach Hall

San Francisco, California

March 9, 2004

by

Rita Felciano

Copyright ©2004 by

Rita Felciano

published March 15, 2004

The simplicity and directness with which this work speaks to the heart is probably unmatched in twentieth century dance. The music in particular can make believers, even if it’s only for the dance’s duration, out of cynics. That is Revelations’ enduring power. But Revelations has also been a golden crutch. Its financial power has been considerable. It has kept the Ailey company not only afloat but financially thriving. The question is whether audiences would continue to flock to Ailey without at least having the chance to see Revelations. One more time.

The indications are that today they might. The choreographer has left another legacy which is maybe more important than one or two really good pieces. Ailey’s vision—the third ‘A’ in the company name—has been exceptionally farsighted and encompassing. Though rooted in the African American experience, he wanted the doors open to the multiplicity of talents that he encountered. It’s this legacy that current Artistic Director Judith Jamison is developing with increasingly impressive results.

Two out of the three programs at Zellerbach, last week, ended with Revelations. In one of them, which I did not see, it was part of an all Ailey selection of excerpts. The other two offered a very satisfying mix of works whose quality suggested that Revelations, without any loss, could and probably should be retired, at least for a while. Despite Amos J. Machanic, Jr.’s beautifully protective partnering of Linda-Denise Fisher-Harrell in ‘Fix Me, Jesus’, this was a mechanistic, routine performance which also needed to be cleaned up on technical grounds. Apparently, the final section, has new costumes. But Revelations needs more than that. There is no reason to keep a work in rep in deference to a tradition and because, no matter, how it gets performed, the audience cheers wildly. It’s time to give Revelations a rest.

Program A’s two Bay Area premieres, Alonzo King’s Heart Beat and Robert Battle’s Juba suggested that Jamison is looking for and finding choreography that challenges her athletically virtuosic dancers and feeds their and our emotional well being.

King’s gorgeous Heart disappointed when the choreographer brought seventeen dancers together for a disconnected finale. Previous to that last section, he had deployed a bare ten of them for in intimate units that resonated with implications. So why bring in these additional dancers in all of a sudden? It should be no news that surprises work best when they have been prepared for. The finale seemed particularly irrelevant since King to this day has not developed effective ensemble choreography. It also wasted a delicate tenderness which struck a fresh and welcome note in this choreographer’s work. The standardized mirroring and line patterns jazzy slinkiness only seemed to undercut what had gone before.

Set to a collection of North African music, Heart gave the Ailey dancers, who so often are asked to be fast and fierce, an opportunity for introspection and nuanced expressiveness. The piece opened on something like daybreak. Dancers, the women in tiny skirts (costumes and design by Robert Rosenwasser), twirled along a diagonal in front of billowing white curtains that looked kissed by, maybe, a rising sun (lighting design by Axel Morgenthaler). Before the first of two central duets, Dwana Adiaha Smallwood’s skippy, little kid solo ended with her beacon-like leg slowly reaching for the sky. Rather than an athletic feat, it looked like an act of consecration. As if, all of a sudden, she had grown up.

The duet for Matthew Rushing and Jeffrey Gerodias, who look like brothers, had the two men engage in a companionable competition, in which they alternatively watched, manipulated and supported each other. Their bodies intertwined and separated much like the musicians’ voices; comfortable in their tenderness with each other and self-suffcient when alone.

The male-female duet for Fisher-Harrell and Dion Wilson paired the two dancer in something along traditional ballet terms with Wilson supporting her elevated walks, swoons over his arm, stiff hops and overhead lifts. Physically elastic, these encounters had a cool but intimate flavor to them. A couple of times, the choreography, a little clumsily, connected to literally to a prominent string sound.

A male trio was followed by another for two men and one woman which was most notable for its sculptural configurations and the way in which Linda Celeste Sims alternated between being the instigator and object of a triangular relationships. Here the ritornello-quality of the music seemed particularly well used.

With its percussively bravura footwork, Robert Battle’s Juba, pays tribute to its African American name sake (a dance performed by slaves) but these athletic body-slapping dancers looked more at home in Eastern Europe than on a Southern plantation. In calf-length black pants, and bluish peasant blouses they danced in lines—once head to toe lying on the floor—holding hands and kicking flexed feet. Rushing seemed to be something of a leader among equals.

John Mackey’s commissioned score for percussion and strings just barely kept Hope Boykin, Samuel Deshauteurs, Abdur-Rahim Jackson and Rushing out of each other’s feet. The sharp attacks of the highly rhythmic patterning had a fiercely insistent quality about them that sent the dancers into something akin to a communal exorcism. Their shuddering torsos and jerky arms at times seemed to explode the togetherness but the center somehow always held.

Yet there was an eerie quality about the way these dancers blissfully smiled at each other while engaged in manic, oppressively compulsive patternings. At one point they looked as if they had stepped out of paintings of the St. Vitus dance, in which medieval peasants are portrayed as engaged in a communal—devil induced--madness of increasingly frenetic dancing.

Elisa Monte’s 1979 Treading, her first choreographic effort, is surely one of her finer works. As performed by Fisher-Harell and Brown, this study of the body as molten ore, pairs the two dancers into a continuously flowing stream of physical encounters that seemed as pre-ordained as the laws of nature.

Starting in silence, the piece opened with Fisher-Harrell unfolding her body from a crouch. In the dark, however, you could more feel than see the presence of another being. It set a tone of mystery and wonder that never lost its pungency. Parts of Steve Reich’s Eighteen Musicians were used as a rather idiosyncratic accompaniment to the couple’s subsequent sculptural encounters and intertwining limbs. Whether strongly imagistic, or more abstract, the meetings looked impersonal as well as erotic. With not a gesture wasted, Treading’s economy of means maintained its mesmerizingly sensuous fascination.

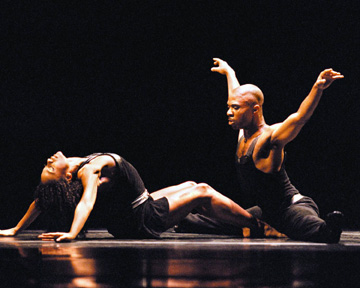

Linda Celeste Sims and Matthew Rushing perform in Ulysses Dove's Episodes, danced on Program C of the Alvin Ailey season at the Zellerbach. Photo: Andrew Eccles.

Originally

published:

www.danceviewtimes.com

Volume 2, Number 11

March 15, 2004

Copyright ©2004 by Rita Felciano

|

|