Engraved Images

Interscape

and Sounddance

Merce Cunningham Dance Company

(presented by Cal Performances)

Zellerbach Hall

UC Berkeley, California

February 7, 2004

by

Rita Felciano

Copyright ©2003 by

Rita Felciano

What

can you say at this point about Merce Cunningham? That he is a genius?

That imagination must be a powerful elixir to keep his wracked body going?

That his dancers look like gods sent to earth for our delection? It has

all been said before by better minds with more insight. And yet, the spirit

aches to hang on to the experience for even a smidgeon. Language can do

that. Imperfectly to be sure, but that's all we have.

What

can you say at this point about Merce Cunningham? That he is a genius?

That imagination must be a powerful elixir to keep his wracked body going?

That his dancers look like gods sent to earth for our delection? It has

all been said before by better minds with more insight. And yet, the spirit

aches to hang on to the experience for even a smidgeon. Language can do

that. Imperfectly to be sure, but that's all we have.

Walking away from a Cunningham performance, having seen those beautiful dancer athletes who have been formed by the same clay, been refined through the same smelting process and yet turned out looking as individually distinct, leaves the heart—as should be clear by now—overflowing.

The second of two programs (the first one featured Biped and Ground Level Overlay) presented two works, twenty-five years apart, Interscape from 2000, and Sounddance from 1975. Both of them in one way or another illustrate the power of ideas. It's well known that music, dance and décor in Cunningham's work come into being independently of each other. So why is it that in the works just seen the co-equal elements again so seamlessly collaborate?

One can only speculate that the artists, however they were talking about the upcoming project with each other, must have communicated some kind of idea, a fluff of a concept, a suggestion of possibilities which then found expression in what we saw on stage. If chance is an essential ingredient to Cunningham's works, maybe it's the idea of chance that accounts for his pieces cohering so logically. Sounddance, a gloriously elegant romp of companionship, has lost none of its delicious freshness. It probably will look just as good twenty-five years down the road. To these eyes Sounddance looks like nothing so much as a pastoral idyll.

Mark Lancaster's golden theater curtain is witty. It looks like leftover velvet from some tiny baroque theater, much too small for a modern stage. There is something pompous and musty smelling about its drooping fabric and hanging scallops. It hangs stolidly and puts up such a solid front. And of course, Cunningham's dancers, slip and tear through it like spirits propelling themselves through walls. Lancaster also dressed the dancers with matching golden tops but then put them in light blue tights which stand out against the curtain. They look fresh and airy with all that gold. They also show the lines of the legs and nicely delineate well-formed butts with which the company is so generously endowed.

David Tudor's lovely layered score, played in surround sound through Zellerbach's excellent amplification system, was full of twittering sounds—some of them suggesting birds-and funny little scratches both natural and electronic. It has an indistinct yet luminously encompassing quality and creates the airy environment in which these dancers so joyfully frolic. How appropriate that senior dancer Robert Swinston should open and close this playful get-together.

A sense of community, of people enjoying each other, however fleeting their interactions, is implicit in most of Cunningham's choreography, but in Sounddance it is spelled out with sometimes surprising literalness. There are circle dances and push-pull lines. Dancers pick up impetus and Simon-Says phrases from each other. They try to pull each other off balance. Like college kids doing the phone booth trick, they pile around and drape themselves over Cedric Andrieux who looks slightly besieged. A woman is hoisted aloft by two men just in time for another dancer to slide under the bridge thus created. A fast little cross-step while pulling on an arm, first performed by Lisa Boudreau in the background, returns towards the end. It looks suspiciously like a tantrum by a kid who doesn't want the party to end.

The forty-five minute Interscape must be one of Cunningham's longer works yet it holds the attention. Some of this is due to the breathtaking brilliance of these dancer athletes' sheer technical achievement but mostly because its individual components cohere so beautifully.

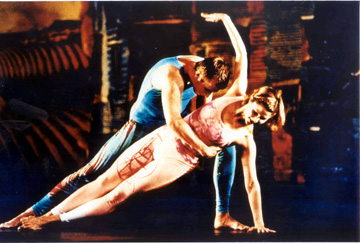

Two primary ideas appear to propel Interscape's luminous trajectory. One looks at the making of images. Clear, separate, distinct images that crystallize, sometimes very slowly, and then are allowed to die. Interscape also is surprisingly gender-specific, with a great number of male female duets to the point that the stage at times almost looks like a ballroom.

Robert Rauschenberg's set is made up of-images. Jumbled, floating, overlapping yet clearly delineated. The Parthenon, a horse's head clad in medieval armor, a partial adobe hut and a partial tenement housing, the top of a cupola, a vacant-eyed mannequin, a duck, an arrow. At first seen in black and white, upon raising the drop curtain, they burst into brilliant color. Rauschenberg also clad the dancers in gender-specific unitards, the men in bright green, the women in splashed prints on top of basic white. Garbed as they were, the men's unisons sweeping across the stage as they did several times, felt like the rush of a spring breeze. One wonders how Cunningham feels about the impact of such costuming.

In the pit Loren Kyoshi Dempster played John Cage's solo for cello One (to the eight). Apparently the piece could also be—but has never been—performed to Cage's 108, a piece for that number of orchestra musicians. This score was so spaced out, airy to the extreme, that at times its presence really did seem accidental though it did move towards more density as the piece progressed. Trying to imagine Interscape with a very big orchestra, makes one think that it might impose a robustness, maybe enhance its sculptural qualities, that currently is more implied than stated.

Rauschenberg's images have permanence and resonate with a verticality of time in a way dance cannot. What dance can and did do is show the "life cycle" images. Interscape seemed fully of them. A woman vertically hoisted overhead, just sat on top of her partner, a totem pole collaged into the backdrop. A hand holding duet revolved from front to back as if on display on a turntable. A man and a woman bent over each other, now touching, now avoiding contact with each others torso. Dancers slowly ascended to very tip of their toes and then breath-takingly hung on to that position.

In Interscape Cunningham also worked with more standard choreographic devices, repetitions, mirror images, canons, but above all he slowed down time, at times almost completely. Maybe he was trying to engrave those images, his and Rauschenberg's, into our consciousness. He did.

Photo: Cédric Andrieux and Lisa Boudreau of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company perform in Interscape (with decor by Robert Rauschenberg). photo: Ed Chappell

Originally

published:

www.danceviewtimes.com

Volume 2, Number 6

February 9, 2004

Copyright ©2004 by Rita Felciano

|

|