Lincoln

Center Festival

Ashton Celebration

Another Chair

"Les Patineurs," "Monotones," and "A Wedding

Bouquet"

Joffrey Ballet of Chicago

Metropolitan Opera House

New York, NY, USA

Thursday, July 8, 2004

by George Jackson

copyright

© 2004 by George Jackson

published July 11, 2004

Chicago,

once the hog butcher of the world, is also a place where the arts have

thrived. The Joffrey Ballet's banishment there has not been into solitary

confinement. Poetry Magazine, the Second City theater scene, Robert Maynard

Hutchins and Mortimer Adler's great books based university, buildings

by Sullivan, Root, Wright and Bauhaus refugees—these are a few examples

of Chicago work that is admired everywhere. The Joffrey's reappearance

in New York after a decade's absence showed a company that is recognizable.

Youthful and functionally trained, the Joffrey is still eager to please.

It suits its Ashton repertory better than before, inhabiting it with an

ease that allowed for subtlety.

Chicago,

once the hog butcher of the world, is also a place where the arts have

thrived. The Joffrey Ballet's banishment there has not been into solitary

confinement. Poetry Magazine, the Second City theater scene, Robert Maynard

Hutchins and Mortimer Adler's great books based university, buildings

by Sullivan, Root, Wright and Bauhaus refugees—these are a few examples

of Chicago work that is admired everywhere. The Joffrey's reappearance

in New York after a decade's absence showed a company that is recognizable.

Youthful and functionally trained, the Joffrey is still eager to please.

It suits its Ashton repertory better than before, inhabiting it with an

ease that allowed for subtlety.

"Les Patineurs" was buoyant, and its star was the corps. The

group of 8 "ice skaters" seemed to have gone to school together,

yet individuals peeked out from among the dancers as from a class photograph.

Not at all superimposed was the romantic couple, Suzanne Lopez and Michael

Levine. Rather, they emerged into prominence. At first, Levine looked

bulky on top in his white costume, yet his dancing and partnering were

as smooth as freshly sharpened blades on an evenly frozen pond. The two

pairs of girls— Deanne Brown and Julianne Kepley, and April Daly

and Erica Lynette Edwards—weren't just replicates of each other.

Each had her own maidenly traits, and Brown was an exceptional turner.

The one alien element was Masayoshi Onuki, in the bravura role of the

solo skater. True, this character is something of a loner, but Onuki's

fine boned build and calculated attack made him seem like someone visiting

from a far away military school. Even so, the Joffrey's "Patineurs"

ushered in the evening delightfully.

When

the "Monotones" ballets, I and II, were first shown in New York

not long after their 1967 and 1966 premiers in London, they restored my

admiration for Frederick Ashton as a choreographer. I had been an Ashton

defender when, in 1949, American critics had received his ballets respectfully

but not enthusiastically on the then* Sadler's Wells Ballet's first visit

to North America. To American eyes of the time, Ashton fell between two

favorite stools—that of Antony Tudor's ballets of psychological

motivation and George Balanchine's musically projected choreography. The

first piece of dance writing I did for eyes other than my own was a letter

defending Ashton against Francis Mason's not-up-to-Balanchine estimate

that appeared in one of that era's important literary quarterlies. I argued

that Ashton deserved a stool of his own, and that at least two of the

legs it stood on were lyricism and finesse. (Mason sent me a very wise

reply.)

When

the "Monotones" ballets, I and II, were first shown in New York

not long after their 1967 and 1966 premiers in London, they restored my

admiration for Frederick Ashton as a choreographer. I had been an Ashton

defender when, in 1949, American critics had received his ballets respectfully

but not enthusiastically on the then* Sadler's Wells Ballet's first visit

to North America. To American eyes of the time, Ashton fell between two

favorite stools—that of Antony Tudor's ballets of psychological

motivation and George Balanchine's musically projected choreography. The

first piece of dance writing I did for eyes other than my own was a letter

defending Ashton against Francis Mason's not-up-to-Balanchine estimate

that appeared in one of that era's important literary quarterlies. I argued

that Ashton deserved a stool of his own, and that at least two of the

legs it stood on were lyricism and finesse. (Mason sent me a very wise

reply.)

After a season or two of Sadler's Wells visits, my enthusiasm for Ashton

waned. His antiquarian ballets ("Sylvia" of 1952, "Ondine"

of 1958, "La Fille mal gardee" of 1960, "Les deux pigeons"

of 1961) showed skill and had moments, yet lacked the miracle of something

new. In these works, Ashton undoubtedly developed his concepts of linearity

and lyricism, yet was doing so in the closet. Other blemishes began to

show—the twee quality sometimes and his inability to reach a choreographic

climax. The late critic Hope Sheridan called Ashton a choreographer of

Platonic love. With "Monotones", Ashton reclaimed his position

as a bold inventor.

Less is more when speaking of the two "Monotones" trios to Erik

Satie music. They are about line—anatomic, musical, temporal, dynamic.

They are about possibility and law, about perpetual motion and absolute

rest. The later "Monotones", the one from 1967 which is danced

first, is cast in jade—the light green in the coloring of its costumes

for two women and a man. It has, perhaps, a hint of Oriental angularity.

On Thursday, I felt that the dancers—Jennifer Goodman, Calvin Kitten

and Stacy Joy Keller—should have repeated their performance and

then would have gotten it right. What we actually saw had no glaring faults.

It didn't, though, start from a point of absolute control and then glide.

This woman-man-woman entity reasserted control throughout the piece and

that seemed against the grain, no matter how hidden the effort.

Less is more when speaking of the two "Monotones" trios to Erik

Satie music. They are about line—anatomic, musical, temporal, dynamic.

They are about possibility and law, about perpetual motion and absolute

rest. The later "Monotones", the one from 1967 which is danced

first, is cast in jade—the light green in the coloring of its costumes

for two women and a man. It has, perhaps, a hint of Oriental angularity.

On Thursday, I felt that the dancers—Jennifer Goodman, Calvin Kitten

and Stacy Joy Keller—should have repeated their performance and

then would have gotten it right. What we actually saw had no glaring faults.

It didn't, though, start from a point of absolute control and then glide.

This woman-man-woman entity reasserted control throughout the piece and

that seemed against the grain, no matter how hidden the effort.

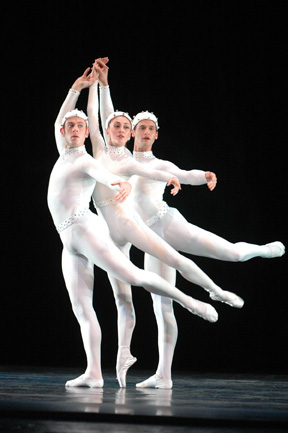

In the second "Monotones" trio, the one a season older, the

lighting is lunar and the symmetry Olympian, with lines defining angle

rather than angle determining lines. Michael Levine, Valerie Robin and

Samuel Pergande were not flawless. Robin slipped at one point, yet it

didn't matter because the dancers were in command of the situation. There

was no visible effort to reassert control. After the accident, the piece

continued as before. Nor was it bothersome that Pergande was taller than

Levine, because they were well matched and wonderful partners for the

remarkable Robin.

The wit and wisdom of "A Wedding Bouquet" and the full joy of

the Joffrey's return to New York were spoiled by lousy acoustics. At the

Metropolitan Opera, of all places, one could hardly understand Christian

Holder's declamation of this ballet's Gertrude Stein text. Lord Berners's

music, sounding great as Leslie B. Dunner conducted it from the pit, helped

drown out the words. Holder's soft Caribbean enunciation didn't help either.

Mostly, though, it seemed the fault of the amplification system that those

delicious lines were muddied. Nevertheless, the non-speaking cast did

very well—Julianne Kepley as Webster, the wedding party's keeper

of law and order, and all the members of the wedding who perpetrate little

sins against propriety, particularly Deborah Dawn's tipsy Josephine, Maia

Wilkins's forlorn Julia, Willy Shives' slightly sleazy Bridegroom, Emily

Patterson's confident Bride and Heather Aagard's not too cute dog. Seeing

"Wedding Bouquet" from two locations during the week, I was

impressed how well the dancers projected to the Met's rafters without

exaggerating for those sitting close. There's a mistake in the printed

program, which referred to the ballet taking place at the beginning of

the 19th Century. Ashton's action, Stein's text and Lord Berners's sets

and costumes clearly place the ballet in the early 20th Century. Wisely,

the Joffrey has not substantially redesigned any of its Ashton ballets,

also using William Chapell's sets and costumes for "Patineurs"

and the streamlined, outside-time costumes for "Monotones".

The wit and wisdom of "A Wedding Bouquet" and the full joy of

the Joffrey's return to New York were spoiled by lousy acoustics. At the

Metropolitan Opera, of all places, one could hardly understand Christian

Holder's declamation of this ballet's Gertrude Stein text. Lord Berners's

music, sounding great as Leslie B. Dunner conducted it from the pit, helped

drown out the words. Holder's soft Caribbean enunciation didn't help either.

Mostly, though, it seemed the fault of the amplification system that those

delicious lines were muddied. Nevertheless, the non-speaking cast did

very well—Julianne Kepley as Webster, the wedding party's keeper

of law and order, and all the members of the wedding who perpetrate little

sins against propriety, particularly Deborah Dawn's tipsy Josephine, Maia

Wilkins's forlorn Julia, Willy Shives' slightly sleazy Bridegroom, Emily

Patterson's confident Bride and Heather Aagard's not too cute dog. Seeing

"Wedding Bouquet" from two locations during the week, I was

impressed how well the dancers projected to the Met's rafters without

exaggerating for those sitting close. There's a mistake in the printed

program, which referred to the ballet taking place at the beginning of

the 19th Century. Ashton's action, Stein's text and Lord Berners's sets

and costumes clearly place the ballet in the early 20th Century. Wisely,

the Joffrey has not substantially redesigned any of its Ashton ballets,

also using William Chapell's sets and costumes for "Patineurs"

and the streamlined, outside-time costumes for "Monotones".

During the very worthwhile first week of the Ashton fortnight at Lincoln

Center, "Enigma Variations" (performed by Birmingham Royal Ballet)

was the highpoint for me. The bill with three companies—Joffrey

of Chicago, Birmingham Royal and K-Ballet of Tokyo—and four ballets—"Rhapsody",

"Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of Isadora Duncan", "Dante

Sonata" and "A Wedding Bouquet"—cumulatively had

a distinct middle-of-the-20th Century aura about it. Some people may consider

that undesirable, but I don't when the ballets are from that period. What

generates the aura may not be choreography and drama as much as spacing,

lighting, scenery, costumes and make-up, although Ashton also wasn't known

to re-choreograph his completed works as much as Fokine or Balanchine.

Curiously, the revised production of "Rhapsody" made it seem

to be an earlier work than it actually is.

* then Sadler's Wells Ballet is now Britain's Royal Ballet of Covent Garden

Photos, all

performance shots by Stephanie Berger:

First: Deanne Brown, Masayoshi Onuki, and Julianne Kelly of the Joffrey

Ballet in "Les Patineurs."

Second: Jennifer Goodman, Calvin Kitten, Stacy Joy Keller in "Monotones

I."

Third: Michael Levine. Victoria Jaiani. Samuel Pergande in "Monotones

II."

Fourth: "A Wedding Bouquet."

Originally

published:

July 11, 2004

www.danceviewtimes.com

Volume 2, Ashton Section

Copyright

©2004 by George Jackson

|

|

|