Mad About the Boy

The Outsider Chronicles:

A Dance-Theater Journey into the World of the Gender Outsider

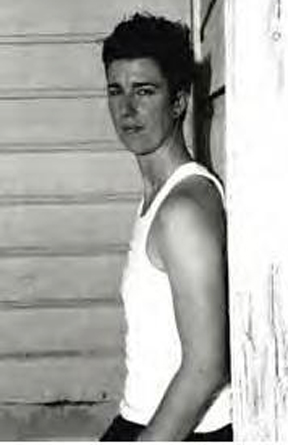

Sean Dorsey/Freshmeat Productions

ODC Theater, San Francisco

November 7-18, 2005

by Paul Parish

copyright ©2005 by Paul Parish

Ovid said his project was to "bring back old things in a new way" (referre idem aliter)—i.e., to mask the old values in new appearances, and gain a kind of delighted shock of recognition when you recognized some familiar virtue in some outlandish unheard-of hero. He'd himself been exiled from Rome into the deepest sticks and was busy unsettling the new Augustan pieties by smuggling in the REAL good-old family values.

Ovid said his project was to "bring back old things in a new way" (referre idem aliter)—i.e., to mask the old values in new appearances, and gain a kind of delighted shock of recognition when you recognized some familiar virtue in some outlandish unheard-of hero. He'd himself been exiled from Rome into the deepest sticks and was busy unsettling the new Augustan pieties by smuggling in the REAL good-old family values.

I mention this since many of the artists who mean the most to me these days are doing something similar—the Coen brothers, Mark Morris, Lynda Barry, the team who made Six Feet Under. All are finding, often through complex plays of tone, ways of revealing some "high" virtue in some "low" context. And right now, I can't remember the last time I saw so much tenderness, romanticism, delicacy of feeling, tentative grace, truth of gesture, human longings for loyalty, affection, and abiding relationship surrounded by such claims to be shocking, bold, futurist, subversive as were in evidence last Friday night at Sean Dorsey's show in San Francisco.

Dorsey has the advantage of having a big talent and an unusual perspective, that of a would-be boy born into a girl's body—and with many of the character traits of a Good Girl. The four love-duets and the quasi-autobiographical solo that made up the evening showed more attentionthe manners, postures, awkwardnesses, eager forays, and stuck moments of embarrassment than I've seen on the dance stage in a long time. The particulars of these slouches, slumps, stuck hips all belong unmistakably to the vernacular body-lingo of teen-aged boys, and without these affectations we would not believe that she thinks she's a boy—but the identification with the boy-world is so transparent, it becomes poignant. They're there, the body reveals the desire; as Martha Graham said, the body does not lie. They show the world she feels she belongs to, that she can't hide that she wants to belong to.*

On top of that, each had an Aristotelian clarity. Each showed a significant event, with a beginning, middle, and end, in the life of young people in love: the first kiss, for example, or the first visit, with a significant other, to the father-whom-you-haven't-told-you're gay.

"Second Kiss" is a piece about the first and ONLY kiss a fourth-grade tomboy gets from the new school diva, collecting it before the belle finds out the awful truth about her beau. This piece sets the model for the rest. There's a short story, full of marvellous detail, written and voice-overed by Dorsey and accompanied by completely appropriate music and performed by Dorsey and Mair Culbreth (the girl), with astonishingly fitting gestures appliqued onto release-style modern dance movement. It could have so easily failed did not Dorsey also have a remarkable literary gift—AND acting skills just this side of Matthew Broderick's, plus a sense of exactly the sound and look the piece needs and a dedicated team who'd kill themselves to get the effects right. The composer/sound recorder/mixer Ben Kessler, using his own music and others', and the lighting designer Clyde Sheets deserve great credit for a show that's not only tight but inspired.

"Second Kiss" really wouldn't have amounted to much were the movement itself not so bien-trouvee. Dorsey's got dead-eye for the tilt of the head, the dropped gaze, the awkward glance, the small flinch of the shoulder, the white-knuckle, the gulp, the dropped jaw, the hanging lower lip, the hopeful gaze (hoping against hope) that comes with eyes wide, chin low, and eyebrows high, which add emotion, inflect the mere motivity with personal feeling and impulse and make the floating, easy-limbed plunges and surges of release-movement into a theatrical medium, punctuate her soft phrases, and make them mean something.

There were four duets; the second ("Red Tie, Red Lipstick," from 2003) told a melodrama of a Lesbian couple who go out on the town and get raped by the cops and I found it slightly phony. (It was the only text not by Dorsey.) The best thing "Red…" was the Restoration Hardware sink set up downstage, and Dorsey's fabulous mime of washing the face and shaving. The dance itself was based inventively on tango posturings and sexy moves, feet darting between each other's legs; the piece added a note of menace to the evening which might have been too sweet without it.

The third ("In Closing) was less a story than a lyric and was the most tender and beautiful thing all evening. I didn't want it to end; the poem closed with a litany of those phrases which end love-letters, "as ever," "yours always," "yours," "yours," "yours," and the whole dance had the quality of idealization as if perhaps the beloved were not actually present. The partnering included allusions to allemande turns ("pretzel-turns," they call them in Zydeco class) where one partner goes under the other's arm, and the highest and most poetic lifts of the evening.

"Six Hours" was a playlet—a six-hour car trip, with the world's coolest new girlfriend, to visit a father who'd called out of the blue and asked the daughter to come; the moment when the stage became the car was a coup de theatre that startled me. The drive is a hilariously awkward process in which the way-to-good-for-this-world girlfriend teases out the truth that the father knows nothing of his daughter's life in town, not even the name she's now going by, and ends with the marvellously ambiguous question, "Would you like to look at a menu, Lauren?" Which one of them is Lauren?

That's a question that doesn't matter if you don't care about the people, but if you do, reticence about it can indicate delicacy of a rare sort. (Nobody knows the name Mr. Ramsay called his wife when he finally had to beg her to forgive him; the only name we have for the heroine of To the Lighthouse is "Mrs. Ramsay.")

The finale, "Creative," I'll let you picture for yourself. The teen-ager is working on her solo to "The boy from New York City" (star-power galore) when rehearsal is cancelled and the guidance counsellor begins the first of ten sessions of "Gender Correction Therapy." All I'll say is that it's hilarious and doesn't strike one false note; "Guidance Gary" is the Church Lady all over again, a fabulous character.

This show could have legs and should be picked up by presenters in New York and DC; I've never been to La Mama, but it could fit into any space that could hold The Fantastiks.

----------

*There's a special problem in writing about Sean Dorsey, since he requests politely that one use the male pronoun in referring to him, although he was born and remains anatomically female. It is a problem of tact, courtesy, respect, of course. BUT it is a problem with a head and a tail—other end of it asks what respect is owed to the social compact, the common language, civilization—since if we grant special dispensations every time they're asked for, it throws a lot of sand into the works: such friction, like a low-grade fever, saps intellectual energy, encourages the fear of giving offense, and puts another nail in the coffin of real English idiom, which can hardly be used anywhere any more.

The interesting aspect of this is the difference between the second and third persons. In addressing Sean directly, all anyone has to say is "you"; it's in talking ABOUT 'him" that a problem arises. For the question arises, what degree of respect is oweing to the person one is talking to (i.e, YOU), and is it greater than or inferior to that which belongs to Sean Dorsey (not his real name)? This isn't too much of a problem when talking to someone, but it arises, Gentle Reader, in YOUR case. Wherever you are, and whoever you are, to whom these words become present, how shall I manage not to confuse you, while respecting the request of Mr/s. Dorsey? And how shall I carry on fearing you may take me for a feninist lackey?

Since the sixties, language has been under such attacks from the disenfranchised ("herstory" instead of "history," etc.); but the first attacks came from the top: since the advent of modernism, the poets themselves (Eliot, Joyce, Gertrude Gertrude Gertrude Stein) have been attacking the common language, trying to "displace" words enough so that they won't have their shopworn dailiness all over them, but will crack open and reveal a fresher meaning as if new-minted.

Dorsey fits into BOTH traditions with his request. I have chosen to follow the example of the Episcopalians, who use both He and She when speaking of God.

Volume 3, No. 44

November 28, 2005

copyright

©2005 Paul Parish

www.danceviewtimes.com

|

|