Ballet Preljocaj

“Empty Moves (Part 1),” “Noces”

The Joyce Theater

New York, NY

November 28 - December 3, 2006

by Nancy Dalva

copyright 2006 by Nancy Dalva

In 1952, Leonard Bernstein, the musical director of the Festival of the Creative Arts at Brandeis University, commissioned Merce Cunningham to choreograph a new version of Stravinsky’s “Les Noces,” which was originally presented by Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes in Paris in 1923. The work was performed only once. It is interesting to think of though, vis à vis Angelin Preljocaj’s recent program at the Joyce Theatre, which ended with his quite ravishing version of the Stravinsky, which he calls simply “Noces,” and opened with a piece, new to New York, that was openly Cunningham-like called “Empty Moves (Part 1)." La plus ça change, and all that, and a novel coincidence. Besides which, Preljocaj studied at the Cunnningham studio in 1980, and later danced for Viola Farber, herself a great Cunningham dancer and former member of Merce’s company.

In 1952, Leonard Bernstein, the musical director of the Festival of the Creative Arts at Brandeis University, commissioned Merce Cunningham to choreograph a new version of Stravinsky’s “Les Noces,” which was originally presented by Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes in Paris in 1923. The work was performed only once. It is interesting to think of though, vis à vis Angelin Preljocaj’s recent program at the Joyce Theatre, which ended with his quite ravishing version of the Stravinsky, which he calls simply “Noces,” and opened with a piece, new to New York, that was openly Cunningham-like called “Empty Moves (Part 1)." La plus ça change, and all that, and a novel coincidence. Besides which, Preljocaj studied at the Cunnningham studio in 1980, and later danced for Viola Farber, herself a great Cunningham dancer and former member of Merce’s company.

“Empty Moves” takes its title from its score, “Empty Words,” a work from 1974 by John Cage (one of those oracular pieces of his where words float up as sounds) heard here in a live recording from Milan’s Teatro Lirico in 1977, which captures a real, as it were, conflama. The audience hoots and jeers and carries on, in increasing intensity, so listening here in New York, you heard Cage, mildly voicing the collage of sound he based on writings by Thoreau, and jolts of angry Italian. (This is a lot of fun, if you like your fun recherché.)

And how pleasant it was to hear Cage’s voice in the Joyce again! Mild, mesmeric, with no word ever really empty in the sense we usually use that term—meaning words empty of sincerity. Cage’s words are full of sincerity, but they float freely and joyously out of context. As for meaning, there is plenty of it, though it tends to be what you put into it. (“Heart and soul at once,” I thought I heard at one point, but maybe not.) And just as there are no truly empty words in the Cage, there are no empty moves in Preljocaj’s playful and purposeful quartet for four dancers attired in trunks and t-shirts, as for gamboling in the tropics. Rather, there are moves without narrative. There is also a vocabulary, built, established, run and re-run.

.jpg) It starts with all four dancers—Isabelle Arnaud, Celine Mari, Yan Giraldou, and Sergio Diaz—bent over as if starting a race. They move in and out of duets, quartets, solos, and complex group configurations. The women sit on the men’s laps like bathing beauties, and then wrap a leg around their necks. There are some playground-looking moves, as when a women squats and then reaches through her legs to grab at someone behind her. In a lovely tangled up section, there are interior lunges, with support given and in alternation. Some slow motion rolls and backwards somersaults look a little like contact improvisation Over time, heat is generated, but not a person-to-person heat. This is a group endeavor, with the dancers using each other like amiable furniture, not as lovers. At one point, there is some child’s or perhaps folk inspired hand slapping (we’ll see this again in “Noces”), at another four distinct solos. As the Italian brouhaha in the score intensifies, there is the interesting phenomenon of the work seeming to intensify, or become more dramatic. Perhaps this is so, but I think it’s a side effect.

It starts with all four dancers—Isabelle Arnaud, Celine Mari, Yan Giraldou, and Sergio Diaz—bent over as if starting a race. They move in and out of duets, quartets, solos, and complex group configurations. The women sit on the men’s laps like bathing beauties, and then wrap a leg around their necks. There are some playground-looking moves, as when a women squats and then reaches through her legs to grab at someone behind her. In a lovely tangled up section, there are interior lunges, with support given and in alternation. Some slow motion rolls and backwards somersaults look a little like contact improvisation Over time, heat is generated, but not a person-to-person heat. This is a group endeavor, with the dancers using each other like amiable furniture, not as lovers. At one point, there is some child’s or perhaps folk inspired hand slapping (we’ll see this again in “Noces”), at another four distinct solos. As the Italian brouhaha in the score intensifies, there is the interesting phenomenon of the work seeming to intensify, or become more dramatic. Perhaps this is so, but I think it’s a side effect.

What the dance has to do with Cunningham is something about movement-for-movement’s sake–in fact, everything about movement-for-movement’s sake. Although there is a notably Merceian section of slow-walking in triplets that would evoke Cunningham for anyone familiar with his work (and in addition a current Cunningham dancer in the house spotted specific passages that reminded him of a lift in Cunningham’s “Un Jour ou Deux,” a quartet in “Changing Steps,” and a part of “Fabrications”) the steps don’t feel like Cunningham. If anything, they feel—and this is odd—more modern, as in clunky, and less balletic, as in purely linear.“Empty Moves” reminded me of “How to Pass, Kick, Fall, and Run,” an antic romp from the sixties, for its tone, and its deceptive casualness. But there was none of Cunningham’s rhythmic complexity, so the resemblance was pleasant, but not deep.

By the end of “Empty Moves,” when you have seen the same phrase facing different directions and realized you are seeing things again, the dance suddenly stops the way it started. Same position. Did it wind itself backwards, or sneak up on itself?

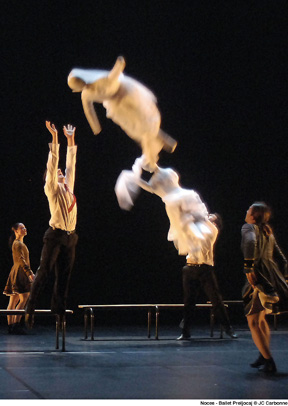

“Noces,” too, ended the way it began, although the moment was communal rather than singular. It began with a girl in a red folkloric looking mini-dress (and fetching little black booties) brought into the center of a dark stage demarcated by five benches. Her hand is over her eyes, and you sense something ominous about to happen. You sense, in fact, that she is a Chosen One, and for a marvelous moment, Preljocaj conflates the Nijinskys—Vaslav’s “Rite of Spring,” Bronislava’s “Les Noces.” The moment passes, though, and soon everyone will be chosen, all five girls, and all five men, and by each other. But first the five women will dance in vivid unison to the music, just so that when the men come in, in white shorts, ties and trousers (one endearingly wears glasses) there is a sudden–well, there is a WOW! moment. Lifts begin, lifts that are a signal pleasure to see. They aren’t just lifts, the are leaps into arms, leaps onto people, cataclysmic pounces and rollings on the floor, to say nothing of what looks like folkloric lap dancing. These are dancers on a mission, possessed and hot. Are they brides and grooms? Is this some kind of rumble? Are the attendants at a wedding?

“Noces,” too, ended the way it began, although the moment was communal rather than singular. It began with a girl in a red folkloric looking mini-dress (and fetching little black booties) brought into the center of a dark stage demarcated by five benches. Her hand is over her eyes, and you sense something ominous about to happen. You sense, in fact, that she is a Chosen One, and for a marvelous moment, Preljocaj conflates the Nijinskys—Vaslav’s “Rite of Spring,” Bronislava’s “Les Noces.” The moment passes, though, and soon everyone will be chosen, all five girls, and all five men, and by each other. But first the five women will dance in vivid unison to the music, just so that when the men come in, in white shorts, ties and trousers (one endearingly wears glasses) there is a sudden–well, there is a WOW! moment. Lifts begin, lifts that are a signal pleasure to see. They aren’t just lifts, the are leaps into arms, leaps onto people, cataclysmic pounces and rollings on the floor, to say nothing of what looks like folkloric lap dancing. These are dancers on a mission, possessed and hot. Are they brides and grooms? Is this some kind of rumble? Are the attendants at a wedding?

Because there are some other brides: eerie person—sized white dollies with truncated limbs and floating veils. Headless, they can be made to twitch and fly through the air with the unnerving sense of something real happening to them, or simply stuffed under one of the benches in a crumpled heap. At first, I thought these dolls were signifiers, that they were the “idea” of marriage, and that the couples were, in playing with them, were toying with the traditional notions of marriage that afflict men and women equally. At one point, one of the women played with one of the dolls as a little girl might, and as little girls still do, dandling her on her knee.

Then the couples went at each other again. In addition to two dollies down, three real women are prone, having hurtled themselves off the benches and onto the mens shoulders, and thence been rolled down onto the floor and, as it were, taken. After covering the women’s bodies, the sit back and chastely pull those folkloric little dresses down over the dancer’s little white panties, which are purely girlish. It’s a moment, but of what? Violation? Vulnerability? Tenderness after the fact? Shame?

Then the couples went at each other again. In addition to two dollies down, three real women are prone, having hurtled themselves off the benches and onto the mens shoulders, and thence been rolled down onto the floor and, as it were, taken. After covering the women’s bodies, the sit back and chastely pull those folkloric little dresses down over the dancer’s little white panties, which are purely girlish. It’s a moment, but of what? Violation? Vulnerability? Tenderness after the fact? Shame?

Slowly, then, the work began to unfracture, to come together as it began, but this time all the girls have their arms over their eyes....As for the dollies, they are hung on the upended benches. You can take this, too, any number of ways. They might be effigies. Or they might just be beautiful and expensive toys put back on their display stands. But that didn’t seem to me the most significant. It was the piece beginning as it ended, just as did “Empty Moves.” There’s something in this about the choreographer saying that he’s invented something, he’s investigated it, and he’s brought it full circle.

Photos:

Top:

The company in "Noces." Photo by J.C. Carbone.

Second: Henri Chaussard, Harald Kritinar, Toshiko Olwa, and Nartracha Grimard in "Empty Moves Pt. 1" Photo by Laurent Philippe.

Third and

Fourth: The company in "Noces." Photo by J.C. Carbone.

Volume 4, No. 44

December 11, 2006

copyright ©2006 by Nancy Dalva

www.danceviewtimes.com