Dryads, satyrs, and an elephant

“Sylvia”

San Francisco Ballet

Lincoln Center Festival

LaGuardia Concert Hall

New York, NY

July 27, 2006

by Mary Cargill

copyright 2006 by Mary Cargill

Love triumphed in New York yet again, as modern dance choreographer Mark Morris visited the groves of an imaginary, pastoral Greece with the San Francisco Ballet. There is an elephant, though, in this peaceful glade, in the form of Sir Frederick Ashton, and, after seeing his magnificent version (which had not been revived when Mark Morris choreographed his), it is almost impossible, if very unfair, not to compare and contrast. Morris, by and large, does come out second, but there are still many fine and beautiful things to see.

Love triumphed in New York yet again, as modern dance choreographer Mark Morris visited the groves of an imaginary, pastoral Greece with the San Francisco Ballet. There is an elephant, though, in this peaceful glade, in the form of Sir Frederick Ashton, and, after seeing his magnificent version (which had not been revived when Mark Morris choreographed his), it is almost impossible, if very unfair, not to compare and contrast. Morris, by and large, does come out second, but there are still many fine and beautiful things to see.

The sets of Morris’ first two acts, I’m afraid, don’t help much; the first scene is set in what appears to be a large paint by number garden, and the second in a giant grey bolt of fabric. Morris’ sylvans, dryads, and satrys cavort much more lustily than the delicate music seems to call for, and Morris sometimes does get a bit too broad—there is far too much breast grabbing. I also found women’s bare legs (only Sylvia in her final pas de deux wore tights) disconcerting, since throbbing tendons and wobbling flesh are neither attractive nor classical.

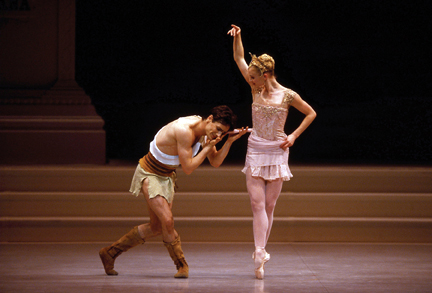

Morris’ choreography for the hero Aminta (danced by Pascal Molat) though, has a refined delicacy and was full of low, fluid attitudes (so appropriately classical and Classical). Molat was just wonderful as the love-sick hero, pure and innocent, with a beautiful shape and flow. Morris’ Sylvia is a feistier heroine than the traditional classical ballerina, and Elizabeth Miner, a tall, leggy blond, with a heroically pure line, made her immensely appealing. One of Morris’ most attractive pieces is the nymph’s dance in the first act, where they are seen swimming in the stream, as Sylvia soars (perfectly timed to the music) above them in a swing straight out of Fragonard. The choreography, with its slightly heavy wading motifs and weighted arm movements, created water out of air and was truly magical. The nymphs, many of them soloists, managed to look both well rehearsed and individual.

Eros, the playful god who controls the destiny of so many, was danced by James Sofranko. Morris’ Eros is playful and capricious, but I think his choreography misses the power and grandeur that also associated with Eros. The costume, a gold-lamé 1920 teddy, didn’t help. This Eros was often the comic relief, but his character should be a more complex metaphor. Love can be comic of course, but it also, in that rational world, had the power to control and rule nature. Sofranko was sparkling, but the role only let him be one-dimentional.

Orion, the hunter villain, Pierre-François Vilanoba, is the stand-in for the violent and uncontrolled emotions that the more coolly rational Enlightenment felt could be defeated. Morris views him somewhat sympathetically, giving him a “Why can’t you love me?” solo in his cave. This cave, despite the magical and colorful music, is rather drab, with a huge rock in the center, which limits the choreography for Orion’s slaves pretty much to stomping and running, though, in a rather blatant attempt for an easy laugh, Morris has four of them mimic a barbershop quartet.

The choreographic highpoint of any classical ballet is usually the pas de deux, and Morris’ has both beautiful choreography and emotional depth. Aminta’s solo is far more than a set of technical tricks; Molat makes it clear that he is the same simple shepherd of Act 1 transformed by joy. Morris’ pizzicato solo does not have the neat, precise footwork that the music indicates, his Sylvia can still jump, but these jumps are full of little grace notes. Miner was both heroic and lyrical. Morris, who has Sylvia return in a pirate ship full of veiled harem girls (who get to dance to some rollicking, enticing music), used the veil motif in the pas de deux, both as a metaphor and to enrich the choreography; it also seemed to be a gentle nod to Petipa’s Nikiya and her shroud.

Unfortunately, Morris’ taste went missing during the final confrontation between Diana and Eros, which Eros reminds the goddess of her love for the shepherd Endymion. The myth tells us that he was in an enchanted sleep on a mountaintop, and that Diana, as the moon, watched over him and his flock. Morris has his Endymion wag his bare buttocks at the audience, which raised a lascivious snicker when it should evoke the image of a lost and unattainable ideal. It may have been the choreography, but Katita Waldo’s Diana seemed more like an aging suburban matron licking her chops at the thought of some young flesh than a goddess bowing down to a superior power.

Though this version is not perfect, it did draw out some very fine performances from the cast I saw; Morris gave the company a real ballet, which required emotional as well as technical abilities, and the cast I saw created true and vibrant characters, even if they had to dance around an elephant.

Photo, by Chris Hardy: Elizabeth Miner and Pascal Molat in "Sylvia."

Volume 4, No. 29

July 31, 2006

copyright ©2006 Mary Cargill

www.danceviewtimes.com