"Death in Venice"

The Hamburg Ballet

Brooklyn Academy of Music

Brooklyn, NY

February 8, 2007

by Lisa Rinehart

copyright ©2007, Lisa Rinehart

John Neumeier is known for making ballets from meaty chunks of psychodrama, and the stew doesn't come much richer than the decline and fall of Gustav von Aschenbach in Thomas Mann's "Death in Venice." Neumeier's balletic version is described as a "free adaptation" of Mann's novella, and von Aschenbach is tweaked from renowned writer to great choreographer whose ideas, memories and unraveling inhibitions are a swirl of danced characters. Using a hefty collage of Bach and Wagner, and a gorgeous set of operatic proportions by Peter Schmidt, Neumeier deftly plumbs von Aschenbach's willing descent. The costuming, a collaboration between Schmidt and Neumeier, is delicious, particularly in the Venetian society scenes throughout which the women waft about in aquatic hues of shimmering chiffon. There's only one hitch — Neumeier, in what I suspect is an attempt to emulate von Aschenbach's tossing off of all restraint, loses his way in the second act and throws in some cheap tricks meant to signify our protagonist's surrender to depravity. They are less than successful. But more about that later.

John Neumeier is known for making ballets from meaty chunks of psychodrama, and the stew doesn't come much richer than the decline and fall of Gustav von Aschenbach in Thomas Mann's "Death in Venice." Neumeier's balletic version is described as a "free adaptation" of Mann's novella, and von Aschenbach is tweaked from renowned writer to great choreographer whose ideas, memories and unraveling inhibitions are a swirl of danced characters. Using a hefty collage of Bach and Wagner, and a gorgeous set of operatic proportions by Peter Schmidt, Neumeier deftly plumbs von Aschenbach's willing descent. The costuming, a collaboration between Schmidt and Neumeier, is delicious, particularly in the Venetian society scenes throughout which the women waft about in aquatic hues of shimmering chiffon. There's only one hitch — Neumeier, in what I suspect is an attempt to emulate von Aschenbach's tossing off of all restraint, loses his way in the second act and throws in some cheap tricks meant to signify our protagonist's surrender to depravity. They are less than successful. But more about that later.

The first act of "Death in Venice" is complex, arresting and very good. Neumeier uses tight, angular arm movements and familiar ballet class phrases to create a convincing, even humorous, portrait of the disciplined, egotistical artist. Von Aschenbach (Lloyd Riggins) has only to twitch a muscle and his dutiful assistant (the wonderfully attentive Laura Cazzaniga) is at his side with coffee, score and the prescience to untie his shoes before von Aschenbach realizes he's ready to rehearse. Riggins' slight physique and world weary demeanor are perfect as his character impatiently poses for photos, accepts awards and snaps his fingers at the dancers while rejecting costume choices. But as von Aschenbach struggles to create what is supposed to be his next masterpiece, he's tormented by self-doubt, and conflicting ideas disrupt rehearsals like a passel of petulant ballerinas. He decides he needs to get away, and ends up in Venice where he meets his destiny; the beautiful, 14-year-old Tadzio (Edvin Revazov, who, as possibly the tallest pre-adolescent around, is nonetheless convincingly gawky and sweet).

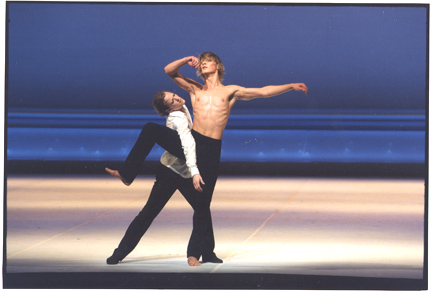

Neumeier handles this psychological turbulence well, supplying spirited dances for the corps (listed in the program as "Sketches"), flashy footwork for the new work's presumed ballerina, "La Barbarina" (Helene Bouchet), and beautifully fluid sequences for von Aschenbach's "Concepts" (Alexandre Riabko and the exquisite Silvia Azzoni). Ivan Urban is equally compelling as "Frederick the Great," a discarded character with flowing hair, and an interesting mixture of refinement and sex appeal with his heavy frock coat swinging open to reveal a bare chest. As Tadzio's friend, Jaschu, Brazilian born Thiago Bordin dances rings around everyone with an infectious exuberance. However, Neumeier's trios for Riabko, Azzoni and Riggins, and a chaste duet for Riggins and Revazov are the choreographic meat of the ballet. As the dancers slide seamlessly from one surprising position to the next, Neumeier shows us the abstract beauty von Aschenbach is striving for. Azzoni, poised en point, her extended leg held up by Riggins, delicately bends to kiss Riabko as he arches below her in a triangulated tableaux worthy of DaVinci's brush.

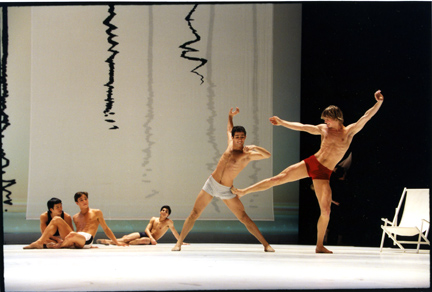

Ironically, when Neumeier strays from such fine balance (as he must in this story about straying), he's less dramatically precise and less interesting choreographically. At the end of Act I, Neumeier introduces von Aschenbach to his inner gay man by way of two bare-chested, jean-clad studs who look like they wandered off the New York City subway at Christopher Street. Their movement is unremarkable; a lot of sidling up to von Aschenbach fore to aft, and straddling various body parts in ways that would excite any repressed Prussian. He then cloaks von Aschenbach's infatuation with Tadzio together with the cholera epidemic in Venice, and gives us an orgiastic roll to Jethro Tull. It's supposed to symbolize von Aschenbach's debauchment, but it's a silly mish mosh of writhing couples awash in acid green light. The two Christopher Street types show up with electric guitars, gold suits and "Kiss" face paint. Really. In the age of legalized gay marriage (almost), are such over-the-top antics necessary to equate latent homosexuality with a penchant for depravity, disease and death? Neumeier's complex weave of characters, and Riggins' admirably nuanced portrayal of an older man undone by his volcanic desire for a beautiful innocent, don't require such visual cliches.

Ironically, when Neumeier strays from such fine balance (as he must in this story about straying), he's less dramatically precise and less interesting choreographically. At the end of Act I, Neumeier introduces von Aschenbach to his inner gay man by way of two bare-chested, jean-clad studs who look like they wandered off the New York City subway at Christopher Street. Their movement is unremarkable; a lot of sidling up to von Aschenbach fore to aft, and straddling various body parts in ways that would excite any repressed Prussian. He then cloaks von Aschenbach's infatuation with Tadzio together with the cholera epidemic in Venice, and gives us an orgiastic roll to Jethro Tull. It's supposed to symbolize von Aschenbach's debauchment, but it's a silly mish mosh of writhing couples awash in acid green light. The two Christopher Street types show up with electric guitars, gold suits and "Kiss" face paint. Really. In the age of legalized gay marriage (almost), are such over-the-top antics necessary to equate latent homosexuality with a penchant for depravity, disease and death? Neumeier's complex weave of characters, and Riggins' admirably nuanced portrayal of an older man undone by his volcanic desire for a beautiful innocent, don't require such visual cliches.

That said, "Death in Venice" is a stunning production with a satisfying dramatic arc. At the end of Act I, in what is perhaps the most poignant moment of the evening, after von Aschenbach has first touched Tadzio's hand in casual greeting, Riggins stands alone on the blank stage, looking at his hands as though they'd been stuck on from another body. In wonder, he raises his arms, palms outward, and looks up as if beckoning us to embrace his downfall as gladly as he knows he will. It's a simple gesture, but Neumeier is good at simplifying complex introspection into imagery that, at its best, spills onto the stage with the ease of gently flowing water.

Photos by Holger Badekow.

Volume 5, No. 7

February 12, 2007

copyright ©2007 by Lisa Rinehart

www.danceviewtimes.com