San Francisco Letter 22

Reggie Wilson/Fist and Heel Performance Group

Yerba Buena Center for the Arts,

San Francisco, CA

February 9, 2007

Black Choreographers Festival: Here and Now 2007

ODC/Theater,

San Francisco, CA

February 16, 2007

by Rita Felciano

copyright ©2007, Rita Felciano

“Diaspora” is one of the most resonant words in the English language. Embodying an awareness of permanent displacement, longing for a home and — almost as a contradiction — a sense of deeply seated community, it has been commonly applied to the Jewish people’s experience but today even more so to African Americans and other exiled peoples. Maybe it’s the complexity of this mix of pain, nostalgia and hope that inspires artists to explore what it means to have roots and yet not be rooted. Two recent evenings of dance intriguingly examined the idea of Diaspora in a variety of manners.

“Diaspora” is one of the most resonant words in the English language. Embodying an awareness of permanent displacement, longing for a home and — almost as a contradiction — a sense of deeply seated community, it has been commonly applied to the Jewish people’s experience but today even more so to African Americans and other exiled peoples. Maybe it’s the complexity of this mix of pain, nostalgia and hope that inspires artists to explore what it means to have roots and yet not be rooted. Two recent evenings of dance intriguingly examined the idea of Diaspora in a variety of manners.

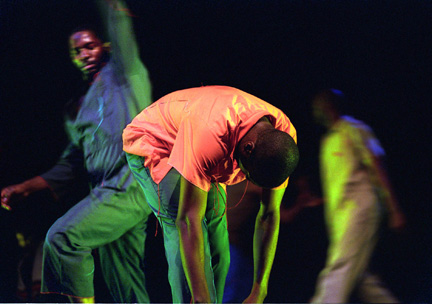

In many ways Reggie Wilson’s premiere appearance in San Francisco disappointed. His company of four brought a set of miniatures, the newest of which dated from 1998. Considering the large scale works which he has traveled, this barely hour long program might play well enough on the college-lecture circuits, particularly since it included an auto-biographical monologue with which Wilson introduced himself and his work. What prompted Yerba Buena Center for the Arts to book this thin introduction to a major artist is inexplicable. If they were hoping to whet the audience’s appetite for more, they succeeded. Wilson’s is a major voice though the short evening left a sour after taste.

This second encounter with the Milwaukee-born artist — I saw “Black Burlesque (Revisited)” three years ago — confirmed a first impression of him as a choreographer of impeccable craft and an uncanny ability to choose music which embraces and deepens to his dance making. Whispering voices between the pieces suggested people trying to reach us across space and time.

“Jumping” is based on an African American wedding custom, maybe going back to Yoruba roots. In Wilson’s hands it becomes a mating ritual of such force that its inexorability is at once funny and awesome. Michel KouaKou is short and wiry and Rhetta Aleong a substantial woman, a fact that hooks into the vaudeville tradition of the hen pecked husband. But Wilson digs deeper. When Aleong backs out of the wings, bent over and swinging a big butt to and fro, she becomes a force of nature, sweeping everything out of the way that keeps her from her goal: a mate. KouaKou may jump this way and that but, as his telling look tells us, the result is forgone. Even as they step hand-in-hand, they already trip each other up, and KouaKou still tries to weasel out of what will happen. And when, after the mating, she grooms him by picking his nose, the gesture establishes female dominance once and for all. Their moaning and groaning coupling fits right in with the old-time, muffled blues recordings.

In “untitled” Aleong slides along in a sitting position along a diagonal beam of light. She is propelled at once by the music from Santeria rituals and by the promise of something at the end of the beam. Wilson suggests a journey into a trance and he does it with the simplest of means. Aleong is rowing with her arms and every once in a while her legs almost slide out from under her. At the end Aleong’s head falls over, she has arrived.

For pure spectacular showmanship it was hard to beat the nervous energy that propelled KouaKou’s “Tales from the Creek.” Bare-chested and in plastic-coated fire engine red pants he shoots across the stage, abruptly changing speed, direction and emotional focus. Sometimes his cross-stepping feet pull him in one way and his wind milling arms in another. In one section he sinks onto two hands, rolls along the floor, hops on his behind and then begins a crawl on all four’s, all within about a ten second phrase. The vocabulary is extraordinarily rich with references to hip hop, jitterbug, stepping, traditional isolations and an athletic kind of modernism, all of it eloquently integrated with moments of quiet where everything is on hold.

Though the piece did not look particularly erotic, there may have been references to liquids beyond the obvious pun in KouaKou and Paul Hamilton ‘s “The Dew Wet.” According to the post-show discussion, the work has been performed by same-sex as well as mixed gender couples. This is a duet about a partnership—somewhat unequal since Hamilton is more than a head taller—based on commonality. These men speak on the same wavelength which leads to tension as well as connection. The most prominent move is a kind of arabesque. “Dew Wet” which is full of suspensions, includes finger gestures that suggest a private sign language. At its most dramatic, KouaKou tries to burrow his head into Hamilton’s belly. It looks both playful and an attempt at penetration.

Not the least of these glances at Wilson’s fine talent, was his solo “Introduction” which started as a verbal presentation but ever so smoothly segues into a kind of rant in which beat boxing moved the literal farther and farther into the realm of poetry.

The Black Choreographers San Francisco weekend — it opened in Oakland the week before — packed the ODC Theater to the rafters. The fact that they did so with local artists, and in the absence of major Bay Area names, says a lot about the capabilities of its co-producers Kendra Kimbrough Barnes and Laura Elaine Ellis. An announcement that the entire take from that evening’s ticket sales would be seed money for next year, must have left other artists present salivating. It also means that this only three year old festival is on solid financial footing in addition to maybe having to look for a bigger venue.

The Black Choreographers San Francisco weekend — it opened in Oakland the week before — packed the ODC Theater to the rafters. The fact that they did so with local artists, and in the absence of major Bay Area names, says a lot about the capabilities of its co-producers Kendra Kimbrough Barnes and Laura Elaine Ellis. An announcement that the entire take from that evening’s ticket sales would be seed money for next year, must have left other artists present salivating. It also means that this only three year old festival is on solid financial footing in addition to maybe having to look for a bigger venue.

Choreographically — this is after all a choreographers’ festival—the solo pieces, for the most part had it over the ensemble works. The most unusual, and freshest of the group choreographies was “Pahupahu” by Mahealani Uchiyama’s who is African American but was raised in Tahiti. She is trained in West African and Polynesian dance and so are some of her dancers. It’s quite a surprise to see her arm swinging and knee-raising, clearly African solo in which she is wonderfully challenged by a drummer, be followed by a half-dozen grass-skirted dancers slide onto the stage, gyrating their hips. At one point one of them steps center-circle and starts an African-inspired solo. The marvel of the piece lies in the ease in which these different — not so different as one becomes quickly aware—styles co-exist so naturally.

“Afriketè”, an ardently performed “premiere”, presented as a work in progress, by Asatu Musunama Hall, framed a personal narrative about transformation into the context of the Olodumare religion. Hall, a member of Emese: Messenger of the African Diaspora music and dance ensemble for whom the piece was created, is a strong, gorgeously expressive dancer. She danced the title role of the daughter, stricken by the death of her mother, to great effect. The way her character went from prostration through weighty and increasingly trance-like movements into some kind of rebirth deserved every bit of the thunderous applause her performance got.

The piece itself, is indeed a work in progress, particularly in the way it moves through space. The choreography for the wind and water Orishas needs to be more clearly defined, and the final water spirits look to much like mermaids manqués. As for the costumes, Hall needs to work with a designer. Musically, “Afrikete” was excellent.

Fua Dia Congo’s wildly joyful “Machinu Mélanger” was about as good a demonstration of the unity of dance and music in African cultures. It would have been impossible to tell who inspired whom, the drums and the call-and-response chanting—picked up by some in the audience — firing up the dancers, or the dancers’ full-force attacks and exultant spirit the musicians. Congolese music has gloriously melodic qualities, always such a pleasure.

The choreography for the three sections, attributed to Muisi-kongo Malonga, Chrysogone Diangouaya and Eloge Mayapela, appeared to move beyond the tried and true circle and line formations. At least two of them had a whimsical sense of humor about them. ‘Mokakatno’ was a stack, almost like football huddle from which chanting arose; “Kingoli,” had the dancers as a chugging with the lone male as their locomotive. Yet neither of them convinced completely. Malonga was by far the best, though not necessarily most energetic, dancer.

The Cuban-born Silfredo La O Viga, unfortunately now a resident of San Diego, contributed a splendid new solo, “Reflection” in which he re-interpreted Ogun, the Candomble God of Iron, a figure not unlike that of Vulcan in Western mythology. The music by Emese performers included hammers working an anvil and thunder sounds. The very tall and very slender dancer La O Viga has a commanding stage presence. His huge steps slice space as sharply as his sword, and the fire in his eyes arises from inside his articulated torso. In the end the dancer picks up a long chain — protection or emprisonment? — and drapes it around his shoulders.

Elvia Marta, best known as a teacher, presented her reworked 1988 “Elusive Illusions. ” As danced by Maria Benjamin, the piece communicated strongly, as a stark and at times devasting portrait of woman torn between reality and what may be a memory. Spare in its design in an almost Grahamesque way but with a simultaneous looseness about it, this was an excellent look at a choreographer of whom we should see more.

The 1988 “Zulu Songs” was Robert Henry Johnson at his best: creating work on his own smooth as taffy and darting like a humming bird body. Johnson’s sense of the stage as his native performance space remains impeccable. But why not show us what he is working on today?

Photos:

Top, Reggie Wilson/Fist & Heel Performance Group. Photo by Antoine Tempe

Bottom, Festival co-producer Laura Elaine Ellis.

Volume 5, No. 8

February 19, 2007

copyright ©2007 by Rita Felciano

www.danceviewtimes.com