Stylish Remakes of Famous Scores

Pascal

Rioult Dance Theatre

Presented by Cal Performances

Zellerbach Hall, UC Berkeley Campus

November 8, 2003

By Rita Felciano

copyright © 2003 by Rita Felciano

Last year Pascal Rioult Dance Theatre introduced itself to Bay Area audiences with a program of emotionally engaging and attractively styled choreography set to Ravel. This year the company is back with Rioult's take on some of Stravinsky's best-known scores: The Firebird, Duo Concertant and Pulcinella Suite. In Rioult's hands Duo became Black Diamond; Pulcinella, Veneziana. The evening closed with Rioult's crowd-pleasing but excellent interpretation of Ravel's bestseller, Bolero.

Choreographing to scores which have already been set by many other choreographers and which are well loved by symphony-goers as well, takes a certain amount of gumption and a willingness to defy the odds. Rioult, whose selections of the Ravel pieces already showed a predilection for going with what is popularly accepted, must feel that his choreography can make us hear the music in ways which we might not have done before. Any other explanation would imply marketing over artistic considerations. But by taking on the tried and true, Rioult also runs the risk of confronting ears that know the music well and eyes that will inevitably set up comparisons. Still, art-making, if it is about nothing else, is about risk-taking. So it was disconcerting to see the superficiality of Rioult's take on both the Pulcinella and The Firebird scores.

For

Veneziana Rioult forewent the madcap Neapolitan commedia dell'arte

story in which Pulcinella and his companion in mischief Furbo wreck havoc

by creating mistaken identities, instigating lovers' quarrels, even faking

their own deaths. Instead he moved his eight dancers north to Venice and

stuck them against Harry Feiner's lovely washed out ink frontice piece

drawing of a spacious baroque plaza. The only reference to carnaval comes

through a veiled figure in red who early in Veneziana streaks

across the stage and sets these puppet-like dancers free. For a moment

they don tiny red masks which, however, are discarded almost before you

notice them. Rioult seems to want to reference carnival yet also prefers

to have a neutral setting for his boy-meets-girl choreography.

For

Veneziana Rioult forewent the madcap Neapolitan commedia dell'arte

story in which Pulcinella and his companion in mischief Furbo wreck havoc

by creating mistaken identities, instigating lovers' quarrels, even faking

their own deaths. Instead he moved his eight dancers north to Venice and

stuck them against Harry Feiner's lovely washed out ink frontice piece

drawing of a spacious baroque plaza. The only reference to carnaval comes

through a veiled figure in red who early in Veneziana streaks

across the stage and sets these puppet-like dancers free. For a moment

they don tiny red masks which, however, are discarded almost before you

notice them. Rioult seems to want to reference carnival yet also prefers

to have a neutral setting for his boy-meets-girl choreography.

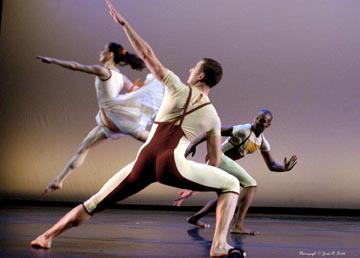

The suite of dances—duets, quartets, the odd trio—slide in and out of two-dimensional graphic images into which the dancers freeze, and a more fully fleshed out use of the body. The idea of moving between these two modes of representation is intriguing, but something needs to happen to them. Repetition alone is not enough. Dressed in short white skirts with red underwear, the girls are frolicking bundles of energy, the boys, in old-fashioned knee length athletic wear, generous and mischievous friends. But the emotional tone never varies, except for a central quartet in which shifting partnerings make an attempt at a softer, more nuanced exploration of relationships. For the most part these skipping, hopping, dropping and strutting encounters remain so unrelentingly buoyant that they freeze the smiles on the dancers' faces. Unremitting cheer becomes tiresome quite quickly—for bother dancers and audiences.

For The Firebird—in the ten episode 1946 version—Rioult made up his own narrative of re-awakening and redemption. Apparently basing it in part on Navajo legend, here the life-giving feather (actually two) is carried by an attractive elementary-school age dancer. Hannah Burnette knows a thing or two about stage comportment; she carries off her thankless task with considerable aplomb. Firebird is dominated by a constructivist-inspired set of dark-hued geometric panels from which dancers' heads pop up or behind which their bodies slink a away. From centerstage hangs a triangular shape that looks as if it is about to fall down and pierce whoever happens to be underneath. The set may look like something out of a '20s Soviet-style theatrical experiments, the skin-tight latex-style black/gray costume, including neck braces, resonate with S/M inflections, or are leftovers from Sigourney Weaver's Alien wardrobe.

Rioult portrays a downtrodden, mechanistic society—think Yakov Protazanov's silent Aelitha-Queen of Mar—which gradually finds or rediscovers its humanity. The awakening doesn't come by way of a growing social awareness as in the 1924 film but by recalling lost innocence or a belief in rebirth. It's a process that is started by Burnette's skipping between stooping, clinched-fist ape-like creatures who jerk, shuffle or scurry along. They crawl on all fours, rear up or collapse into primordial ooze. Burnette wafts the feathers that are taller than she is. She prods individuals; she climbs over their shoulders, she embraces their knees. Gradually you sense that these people are trying to break out of their encasements. They push against invisible membranes, shielding their eyes from the entering light. They awkwardly entangle each other, engage in a fierce collision to finally burst into great leaps into the air. Rioult's choreography is as much a portrayal of evolution as it is of salvation.

Unfortunately, Rioult's means to embody this grand scheme of good overcoming evil, are just too simplistic. He rides the music instead of going inside it. The work is rhythmically monotonous, and if there were fresh movement ideas, they were difficult to discern. On a fundamental level, however, the proposition that innocence portrayed as simplistically as it was here, could overcome depravity, as monolithic as seen here, simply stretched credulity beyond the suspension of disbelief.

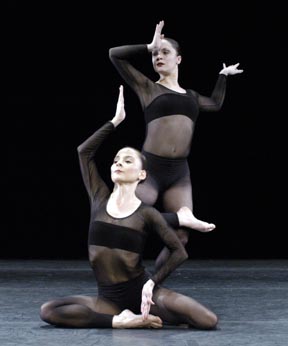

Black

Diamond on the other hand is a wonderful piece. Sharply etched, it

presents two black-clad dancers (a sinuous Lorena B. Egan and edgy Penelope

Gonzalez) on two boxes, placed upstage into a darkened environment, David

Finley designed the excellent lighting. With not a narrative gesture in

sight, except for the drama of two bodies dancing with, against and for

each other, Rioult explores the music's quicksilvery give and take with

passionate lyricism and great formal restraint. When the violin and the

piano tumble over each other with rhythmic overlaps or sinuously curl

around each other, the dancers maintain their own quicksilvery give and

take at first from a lofty distance then through an incremental rapprochement.

The work starts with mirror images of legs swinging, coming to a momentary

rest in attitude and little side steps. Maybe the dancers are trying out

their space. Their soft edged lyricism is countermanded by the individual

phrase's finely realized placement. A faster paced section of fast jerks

and rolled hips smoothly segues into the third movement by which time

Gonzalez has descended from her lofty box. First she slithers down to

a smaller one, then slides onto the floor into a pool of light. This is

where the compatability and difference between those women becomes particularly

accentuated. Egan retains a lofty, slightly more distanced grandeur to

Gonzalez fleet-footed dancing. The Gigue, with its scurrying and pivoting

in place and taking of turns of watching each other, becomes both a darting

competition and a lovingly playful interlude until at the end equality

and calm is restored.

Black

Diamond on the other hand is a wonderful piece. Sharply etched, it

presents two black-clad dancers (a sinuous Lorena B. Egan and edgy Penelope

Gonzalez) on two boxes, placed upstage into a darkened environment, David

Finley designed the excellent lighting. With not a narrative gesture in

sight, except for the drama of two bodies dancing with, against and for

each other, Rioult explores the music's quicksilvery give and take with

passionate lyricism and great formal restraint. When the violin and the

piano tumble over each other with rhythmic overlaps or sinuously curl

around each other, the dancers maintain their own quicksilvery give and

take at first from a lofty distance then through an incremental rapprochement.

The work starts with mirror images of legs swinging, coming to a momentary

rest in attitude and little side steps. Maybe the dancers are trying out

their space. Their soft edged lyricism is countermanded by the individual

phrase's finely realized placement. A faster paced section of fast jerks

and rolled hips smoothly segues into the third movement by which time

Gonzalez has descended from her lofty box. First she slithers down to

a smaller one, then slides onto the floor into a pool of light. This is

where the compatability and difference between those women becomes particularly

accentuated. Egan retains a lofty, slightly more distanced grandeur to

Gonzalez fleet-footed dancing. The Gigue, with its scurrying and pivoting

in place and taking of turns of watching each other, becomes both a darting

competition and a lovingly playful interlude until at the end equality

and calm is restored.

Bolero brought this mixed show to a satisfying finale. Rioult wonderfully tapped into the mechanical exercise quality of this most famous of Ravel's scores. Dressing his dancers in metallic unitards, imparted a hint of a sci fi. For the ensemble Rioult devised tiny piston-like unisons for the torso and angular robotic gestures for the arms. The patterns started in place but gradually opened into stacked lines, a diagonal and finally a circle that opened and closed like a photographer's lens. Out of this uniformity, individual dancers broke into open bodied stretches, arabesques and spiral turns. They set up striking contrasts to the ensemble's inexorable progression which inevitably would suck up the soloists again. It is a measure of Rioult's skill and understanding of this on the surface so simple score that he introduced us to his "instruments" as imperceptibly as Ravel did. To have a score like this one still reveal secrets is no small accomplishment for any choreographer.

Photos:

First: Michael Spencer Phillips (foreground), Penelope Gonzalez and Royce

K. Zackery of Pascal Rioult Dance Theatre perform in Veneziana.

Photo credit: Janet Levitt.

Second: Penelope

Gonzalez (standing) and Lorena B. Egan (sitting) of Pascal Rioult Dance

Theatre perform in Black Diamond. Photo credit:Richard Termine.

Originally

published:

www.danceviewtimes.com

Volume 1, Number 7

November 10, 2003

Copyright ©2003 by Rita Felciano

|

|

|