Monotones

I and II, Thais pas de deux, Symphonic Variations, Elite Syncopations

San Francisco Ballet

War Memorial Opera House

San Francisco, California

Tuesday, April 13, Friday April 16, Saturday April 17, 2004

By Paul Parish

Copyright

© 2004 by Paul Parish

published 19 April 2004

The

opening night performances of San Francisco Ballet's centennial tribute

to Frederick Ashton looked uneasy and stiff—which should not be

surprising, given that it fell between the Balanchine centennial programs

(which is their metier) and the season finale, the world premiere of Mark

Morris's new version of Sylvia, which opens week after next and

was made for them. (They've been rehearsing Sylvia for months, shown it

to select audiences who've loved it, and have every reason to believe

it will be a smash—some performances are already nearly sold-out.)

So the Ashton program is wedged in this niche—and Ashton's style

is NOT one they're trained in. It was bound to take a while to get it

to look natural, and the only time available was during the run.

The

opening night performances of San Francisco Ballet's centennial tribute

to Frederick Ashton looked uneasy and stiff—which should not be

surprising, given that it fell between the Balanchine centennial programs

(which is their metier) and the season finale, the world premiere of Mark

Morris's new version of Sylvia, which opens week after next and

was made for them. (They've been rehearsing Sylvia for months, shown it

to select audiences who've loved it, and have every reason to believe

it will be a smash—some performances are already nearly sold-out.)

So the Ashton program is wedged in this niche—and Ashton's style

is NOT one they're trained in. It was bound to take a while to get it

to look natural, and the only time available was during the run.

These artists are very quick—by the week-end, Monotones had developed a heady atmosphere, and Symphonic Variations had begun to open up its secrets.

It was tempting, after opening night, to concentrate on the difference between Ashton and Balanchine. "Balanchine is so about movement," as one very smart friend said, "and Ashton is so much about shapes"—which is true, especially about these ballets. As soon as she said it, I saw the three ballerinas in Symphonic Variations wrapping their legs into attitude around the central man. I also remembered how astonishingly close Julie Diana had come, in Fonteyn's role, to looking like Fonteyn—Diana can do an Ashton arabesque, with beautifully diminished ribs, an eloquently, carefully shaped back, and softly molded, low, round shoulders. She even has the English ballerina face—bee-stung lips, huge soft wide-spaced warm eyes; she could be blood-kin to Sibley or Seymour or Park. And she can do a sissonne from nowhere, like Merle Park.

Competing with that was a flash on the image of Nicholas Blanc throwing his head back into a noble cambre in mid-pirouette and continuing to circle in this magnificent posture, like Mercury whirling on a cloud, in a glorious sequence (in Brian Shaw's role) that was not matched by others later in the week.

But nagging against all that was the feeling that I'd seen the dancers working too hard, thinking too much, having to remember to do "those arms"—how constrained they'd seemed, by contrast to the memories I had of seeing Ashton's ballets at Covent Garden decades ago when I was a student at Oxford: they made me love ballet. Ashton was still director, and there was still atrace of the Old Vic about the ballets; the dancers knew something about impersonating fairies, princes, Nereids, the four winds, Illyrians, Anacreontic shepherds, demi-gods, all sorts of poetic fantasies that had to be given a face, a way of moving, and essential energy, and a characteristic something to do.

Ashton's ballets circa 1970 were danced by great artists who'd grown up in his style. It was a new art to me then, and it was his style, his dancers and his ballets and his version of Swan Lake that made me realize that dancing was something you could think about, that indeed I had to think about it. What I remember best is how fluent they were, how intelligible, how musical, and how physically confident the dancers were. Sibley's arms were as fluid as a bird's: her whole body's involvement in the dancing was intoxicating. They owned their movement as much as Balanchine's dancers did theirs—it was just different movement.

It was also tempting to wonder how Symphonic Variations might have changed, if like Balanchine, Ashton had remained the active artistic director and adapted his old ballets to new dancers on into the 70's. This especially since I'd heard earlier in the week how Concerto Barocco had changed since the 50's, from the post-war SFB ballerina Nancy Johnson: "Barocco used to very round," she said, while placing her arms in Cecchetti positions (high fifth, middle fifth) that made me think instantly of Symphonic Variations. (Johnson was talking to a small crowd at the Performing Arts Library and Museum about how Lew Chistensen had brought the Balanchine influence to San Francisco, "opening up the movement,' in SFPALM's excellent Balanchine centennial series, curated by Sheryl Flatow).

But that was just a passing irony—it's not at all likely that Ashton would have changed the arms. What impressed me most about the SFB performances was how they grew as the dancers "got into" the ballets, how many of the dancers seemed to embrace the kind of beauty Symphonic Variations contains and to take on its challenges—especially Elizabeth Miner in the second cast, and Joan Boada in the first, whom I'd never have expected to look so refined: he was calm, noble, happy, thoroughly at home in its confines…. I got no feeling that he wanted to do entrechat-six instead of soubresaut, or take any liberties with the choreography.

Symphonic Variations remains mysterious to me. I do hope SFB brings it back next year, for I have not seen enough of it by any means. It was not in the reperory when I lived in England, so I never saw it with its great exponents; indeed, this is the first time I've seen it live and in three dimensions—and video does not do justice to its monumental, sculptural depths. I was fascinated to see how beautiful the men were, standing at the back of the stage like columns across a temple.

The three men in Symphonic Variations don't move for nearly ten minutes—indeed, we don't even see their faces. They stand in noble positions, like patience on a monument, heads in profile looking offstage, with their weight on one leg, the other bent at the knee, foot crossed over in front. This contrapposto is enormously satisfying to look at—it's a version of the Praxitelean stance, with the weight more on one foot than the other, which gives such rhythm and apparent movement to the great statues of classical Greece. So although it's still, it is pregnant with movement; it is indeed the simple version of the fantastic attitude pencheés of the supported adagio which are the most memorable of the extended positions to me. Still, it seems characteristic of this ballet that the MOST memorable images are still poses, on the flat foot—the women leaning sideways with their arms crossing their bodies in straight lines, waiting for the men to waken and come to them.

Monotones

I and II (a ballet that's been in the repertory since Michael Smuin's

day, i.e., 1981) took a long time to develop atmosphere in this run.The

music of Satie's Rosicrucian phase casts a druggy spell, and the dance

must be keyed to it so intimately that its weirdness seems to appear in

the images that emerge and decay in time with it —fast apparition,

slow decay, like music in an echoing chamber. By Saturday, Muriel Maffre's

developpés were opening with a majesty and inevitability that took

your breath away. (Indeed, there was no second cast in SF for Monotones

II; Maffre, Brett Bauer, and Moises Martin did all seven performances,

Martin despite an injury—so they had time to develop the group mind

so necessary to the seamless openings and closings of that dance, which

must be so smooth as to seem visionary, or the manifestations that happen,

usually on the second beat of these eerie mazurkas, have no point to them.)

Ashton said that part of the impetus for Monotones came from

seeing Merce Cunningham's ballet Septet, which is also set to

haunting music by Satie, and on Saturday I could feel a connection between

Maffre's mystery and the sphynxlike quality of Carolyn Brown, whose uncanny

quality in Cunningham adagios is well documented on film and any Ashton

fan should check out—it must be seen to be believed.

Monotones

I and II (a ballet that's been in the repertory since Michael Smuin's

day, i.e., 1981) took a long time to develop atmosphere in this run.The

music of Satie's Rosicrucian phase casts a druggy spell, and the dance

must be keyed to it so intimately that its weirdness seems to appear in

the images that emerge and decay in time with it —fast apparition,

slow decay, like music in an echoing chamber. By Saturday, Muriel Maffre's

developpés were opening with a majesty and inevitability that took

your breath away. (Indeed, there was no second cast in SF for Monotones

II; Maffre, Brett Bauer, and Moises Martin did all seven performances,

Martin despite an injury—so they had time to develop the group mind

so necessary to the seamless openings and closings of that dance, which

must be so smooth as to seem visionary, or the manifestations that happen,

usually on the second beat of these eerie mazurkas, have no point to them.)

Ashton said that part of the impetus for Monotones came from

seeing Merce Cunningham's ballet Septet, which is also set to

haunting music by Satie, and on Saturday I could feel a connection between

Maffre's mystery and the sphynxlike quality of Carolyn Brown, whose uncanny

quality in Cunningham adagios is well documented on film and any Ashton

fan should check out—it must be seen to be believed.

Equally visionary was Julie Diana's veil-dance at the Saturday matinee in the Thais Pas de deux (set by Sir Anthony Dowell)—partly because Vadim Solomakha made her seem visionary. He is a dreamy dancer, and they both have a romantic quality, the ability to make you see them breathing, so that his arms open as an extension of his breath as the possibility of touching his vision becomes more and more a reality—and then he plucks her out of her bourrées and lifts her like a breath. They were not first cast—probably because Diana was first-cast for Symphonic Variations—but the first cast did not have the effortless quality these two did. Which was particularly remarkable since Diana's veil got stuck to her crown and was deftly removed by Solomakha. It lay in the wrong place on the stage for the entire dance—until she made her final exit, and drifting across the back bent down picked it up, and flung it over her face, bourréeing ecstatically backwards gesturing imploringly with her empty arms. Until their performance I could not see why Marie Rambert could have thought it a great ballet.

The evening closed with MacMillan's Elite Syncopations—which was a hit last year, the company already has down pat, is a hit with the audience and clearly a pleasure for them to dance. It would have been great if they'd put another Ashton ballet on the program, but it would not have been realistic to try. A saving grace was to notice how often MacMillan uses that pose so characteristic of Symphonic Variations, with one foot crossed in front of the standing leg. It is ALL THROUGH Syncopations—can that be an accident? It's not a position that's that much in use. In any case, it's characteristic of these dancers to show you the family resemblances between ballets, and let you see the links that hold it all together. They made it look like an homage to Ashton.

................................................................

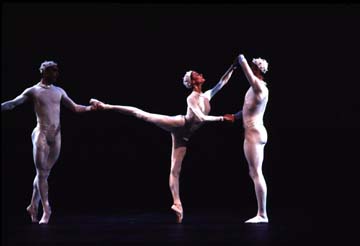

Monotones

Iand II were staged by Lynn Wattis (assisted by Ashley Wheater); Symphonic

Variations by Wendy Ellis Somes

Photos:

MonotonesII: Moises Martin, Muriel Maffre and Brett Bauer in Ashton's

Monotones II (photo by andrea flores)

Symphonic Variations: Tina LeBlanc, Damian Smith, Julie Diana,

Vanessa Zahorian (photo by andrea flores)

Originally

published:

www.danceviewtimes.com

Volume 2, Number 14

19 April 2004

Copyright ©2004 by Paul Parish

|

|