“Celebrating Diaghilev” at the Royal Ballet

Le Spectre de la rose, L’Après-midi d’un

faune, Les Noces, Daphnis and Chloë

The Royal Ballet

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

London, England

May 2004

by

David Vaughan

copyright

© 2004 by David Vaughan

Like nearly every major ballet company nowadays, the Royal Ballet follows the practice of presenting a full-length ballet or a program of one-acts devoted to a “theme” for a certain number of performances, and then dropping it. One might prefer the old system, which I believe only New York City Ballet still preserves, of maintaining a repertory of ballets and showing them in various combinations during a given season, but probably as much for marketing as for artistic reasons, the “theme” idea seems to be what we are stuck with. As its last mixed bill of the 2003-2004 season, the Royal Ballet presented during May a program of four ballets under the rubric “Celebrating Diaghilev” (specifically, the 75th anniversary of his death and the consequent demise of his Ballet Russes): Fokine’s Le Spectre de la rose, Nijinsky’s L’Après-midi d’un faune, Nijinska’s Les Noces, and a revival of Frederick Ashton’s Daphnis and Chloë. It might be argued that the fourth ballet should have been by Balanchine, but both surviving ballets of his from the Diaghilev era, Apollo and Prodigal Son, have been given in all-Balanchine evenings over the last two seasons. In any case, from my point of view no excuse was needed to bring back an Ashton masterpiece last seen in an unsatisfactory recension.

Ashton

created his version of Daphnis in 1951, encouraged (as he so

often was) by Tamara Karsavina to “rescue” Ravel’s great

score from the concert hall and restore it to the stage, and to do so

not in a way that evoked antiquity, but as a work of contemporary relevance.

He chose as his collaborator the English painter John Craxton, who had

lived in Crete for many years and had a strong sense of the continuing

potency in Greek life of ancient beliefs and customs. (Craxton, by the

way, was the first designer of Apollo for the Royal Ballet.)

An important element of this new revival is the restoration of Craxton’s

designs, supervised by the artist himself. The decors evoke the “wine-dark

seas” of the Aegean and the sun-bleached landscapes of Greece. The

costumes for the women in the corps de ballet are dirndls in bright colors,

the men are in shirts and pants.

Ashton

created his version of Daphnis in 1951, encouraged (as he so

often was) by Tamara Karsavina to “rescue” Ravel’s great

score from the concert hall and restore it to the stage, and to do so

not in a way that evoked antiquity, but as a work of contemporary relevance.

He chose as his collaborator the English painter John Craxton, who had

lived in Crete for many years and had a strong sense of the continuing

potency in Greek life of ancient beliefs and customs. (Craxton, by the

way, was the first designer of Apollo for the Royal Ballet.)

An important element of this new revival is the restoration of Craxton’s

designs, supervised by the artist himself. The decors evoke the “wine-dark

seas” of the Aegean and the sun-bleached landscapes of Greece. The

costumes for the women in the corps de ballet are dirndls in bright colors,

the men are in shirts and pants.

Ashton’s choreography includes several different idioms: stylized folk-dance for the shepherds and shepherdesses and for Chloë’s solo in the third scene; “archaic” poses; pure danse d’école for some of the ensembles, notably that in which the four principals are in a line across the stage (the signature “Fred step,” or half of it anyway, occurs here); in the dance competition between Daphnis and his rival, Dorcon, grotesque movements for the latter and a kind of limpid classicism for the former. (As far back as Nocturne in 1937 Ashton choreographed male solos to adagio music--cf. the Prince’s friends in Cinderella, Beliaev’s solo in A Month in the Country, among other examples.) I thought I detected a reminiscence of Massine’s slide to the floor in the Miller’s farucca in Tricorne in the dance of Bryaxis, the pirate chief—and Alexander Grant, the creator of the part, had danced the Miller not long before.

Yet these disparate elements are bound together by Ashton’s infallible sense of choreographic structure, both in terms of the relation of the parts to the whole and—an important aspect of his musicality—of the way in which things happen at exactly the right moment in the music. Louis Horst himself would have approved the way in which that dance of Chloë’s, to the flute solo, is constructed out of three or four basic steps. (It is said that when Mark Morris, that self-described “structure queen,” saw a tape of Margot Fonteyn rehearsing it, he said it was “the greatest thing I ever saw.”)

It must be said that neither of the two dancers who performed the role in the first two performances of the revival came anywhere near Fonteyn; after all, Ashton himself said once that this was the role in which he missed her the most. (Alina Cojocaru was to have danced it, but had to withdraw because of injury.) Jaimie Tapper has shown herself to be an Ashton dancer, in the solo from Sylvia that she performed in the great Fonteyn conference a few years ago, and in the pas de trois from Les Rendezvous, and there were moments when her performance was touching and beautifully danced. MiyakoYoshida was too perky in the first scene, almost like a teenager, but she came into her own in the solo with bound wrists in the second scene, when she pleads with the pirates to spare her.

Federico Bonelli as Daphnis may have been a bit pallid as to characterization, but he danced the competition solo very well indeed. Unfortunately Johan Kobborg was not scheduled for this part, for which he would be marvelously well suited. (Mary Clarke’s recent observation in the Dancing Times that Kobborg seems to have had an influence on the Royal men as far as their landings in fifth position are concerned was borne out here.) Laura Morera was the better of the two Lykanions that I saw, and Martin Harvey the better Dorcon. One thing that didn’t quite happen for me this time was the feeling of the numinous in the exquisite trio of the Nymphs at the end of the first scene; it may well appear when the three dance more together. But that atmosphere was captured at the end of the second scene, when Pan’s appearance causes the pirates to jerk every which way.

The Royal Ballet gave its audiences a useful dance history lesson in the rest of this program—with the help of Lynn Garafola’s excellent essay on Diaghilev in the program book. (In other ways this publication left much to be desired.) One could trace the development of modernism in his company’s repertory from Mikhail Fokine’s Le Spectre de la rose through Vaslav Nijinsky’s L’Après-midi d’un faune to Bronislava Nijinska’s Les Noces. Not that Spectre is really an example of Fokine’s radical reform ballets—a Biedermeier vignette made to show off the talents of Nijinsky. But it is one of the few Fokine works that are made up of steps and not the kind of plastique that tends to disappear in recent revivals. These were said to be the first performances of the piece by the Royal Ballet, and certainly that is true as far as the company’s tenure at Covent Garden is concerned. But everyone seems to have forgotten that it was given by the Sadler’s Wells Ballet at the New Theatre (now the Albery) in 1944, when it was designed by Rex Whistler, and danced by Alexis Rassine and Margot Fonteyn (who must have been coached by Karsavina). This time the original Bakst designs have been restored—but with no birdcage, alas! (I hope someone will soon go and buy one.)

Carlos Acosta, that wonderful artist, can certainly do the steps, but in every other way was badly miscast here. The Spectre should be danced by a smaller man, one who can suggest androgyny (as Baryshnikov memorably did), and Acosta should not be given a costume in shocking pink rather than rose. Ivan Putrov, one of the Royal’s Russian dancers, was exactly right, as was his partner, Leanne Benjamin. (Acosta’s was Morera, replacing Tamara Rojo, perfectly acceptable.) On the other hand, Acosta was magnificent as the Faun, with one of the Royal ’s most intelligent dancers, Zenaida Yanowsky, as the leading Nymph, both of them matched in their unwavering focus on the movement (and the stillness) and on each other. This version was reconstructed by Ann Hutchinson Guest and Claudia Jeschke from Nijinsky’s own notation, which they painstakingly deciphered. Although Ivor Guest, in his program note, writes that the standard version danced by other companies, derived from Woizikowski’s staging in the early days of the Ballet Rambert and later remounted by members of that company, is a “caricature,” it seems to me that it is at least true to the spirit of the work if not (in every detail) the letter.

There can be no disputing the authenticity of the Royal production of Les Noces. One of the most important things that Ashton did during his time as director of the company was to rescue Nijinska’s two masterpieces, Les Biches and Les Noces, from oblivion, and it is to the eternal credit of the company that it has maintained them in repertory, even though in the beginning Noces was pretty much box-office poison. The ballet has since entered several other repertories, including those of the Paris Opéra, the Kirov, and (all too briefly) Dance Theater of Harlem, but it is safe to say that no other company has danced it with the commitment, and the accuracy, of the Royal Ballet, and it was moving to see it performed now by a new generation of dancers who did not learn it from Nijinska herself. One of the few people from an earlier generation is Genesia Rosato, one of the company’ s finest artists, as the Bride’s Mother. Predictably Yanowsky is perfect as the Bride, but it is of course essentially an ensemble work, surely the greatest ballet of the 20th century. And the company’s perseverance has paid off—the ballet has found its audience, who gives it the ovation it deserves. One of the most encouraging things about this program is that it shows that mixed bills can sell, even at Covent Garden.

Photos:

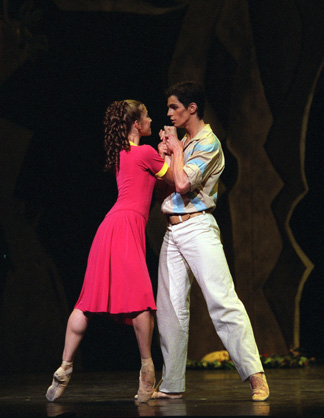

First: Jaimie Tapper as Chloë Federico Bonelli as

Daphnis in Daphnis and Chloë photo by Dee Conway

Second: Marianela Nunez as Lykanion and Federico Bonelli in Daphnis

and Chloë photo by Dee Conway

Originally

published:

www.danceviewtimes.com

Volume 2, Number 19

May 24, 2004

Copyright ©2003 by David Vaughan

|

|