HOW TO....

The Merce Cunningham Dance Company will perform “How to Pass, Kick, Fall, and Run” on the opening night program of C ity Center's Fall for Dance Festival (September 28th).

By

Nancy Dalva

copyright

© 2004 by Nancy Dalva

published September 27, 2004

In

the past year, The Merce Cunningham Dance Company has performed “How

to Pass, Kick, Fall, and Run” in, among other cities, Chicago and

Washington D. C., and it is the final work on the opening night program

of the Fall for Dance Festival on September 28th at City Center in New

York. Dance Theatre of Harlem, Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company,

STREB, and David Neuman will precede the company on the mixed bill. As

it happens, Mr. Jones is an admirer of Mr. Cunningham’s work, as

is Elizabeth Streb. She was in turn admired early on in her career by

John Cage and Mr. Cunningham—who recommended her work to me in the

early 1980s—so the program makes a certain amount of sense as something

other than a random sampler. Besides, “How To” is the only

work in the Cunningham repertory in which the choreographer himself still

takes a part, and it is nice to think of him being on stage again at City

Center, where his company for so many years performed every spring.

In

the past year, The Merce Cunningham Dance Company has performed “How

to Pass, Kick, Fall, and Run” in, among other cities, Chicago and

Washington D. C., and it is the final work on the opening night program

of the Fall for Dance Festival on September 28th at City Center in New

York. Dance Theatre of Harlem, Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company,

STREB, and David Neuman will precede the company on the mixed bill. As

it happens, Mr. Jones is an admirer of Mr. Cunningham’s work, as

is Elizabeth Streb. She was in turn admired early on in her career by

John Cage and Mr. Cunningham—who recommended her work to me in the

early 1980s—so the program makes a certain amount of sense as something

other than a random sampler. Besides, “How To” is the only

work in the Cunningham repertory in which the choreographer himself still

takes a part, and it is nice to think of him being on stage again at City

Center, where his company for so many years performed every spring.

Mr. Cunningham made “How To Pass, Kick, Fall, and Run” in

1965, with the premiere being given in Chicago on November 24th. In the

cast (as noted by David Vaughan in “Merce Cunningham: Fifty Years,”

published by Aperture ) were Carolyn Brown, Barbara Dilley Lloyd, Sandra

Neels, Albert Reid, Peter Saul, Valda Setterfield, and Gus Solomons, Jr.

(The choreographer later added a part for a fifth woman, which has recently

been dropped.) Mr. Cunningham appears today not in his original part,

which is danced by Robert Swinston, but in the part of Mr. Cage, who devised

the accompanying sound text. The current iteration—the meticulous

reconstruction was undertaken by Mr. Swinston, who is the assistant to

the choreographer—retains the antic charm of the original, augmented

by a new poignancy, particularly in the opening and closing moments of

the piece, which runs a little over twenty minutes.

At

the opening of the work as it currently is presented, Mr. Cunningham is

seated at a table to the far left of the stage, on the part called the

“apron.” At his right is David Vaughan, in his own original

role as one of the narrators of the score, which is a series of vignettes,

of varying lengths, each read aloud so as to take up exactly a minute.

(Thus some are spoken rapidly, some slowly, some somewhere in between.

Sometimes the narrators overlap. The material was drawn by Mr. Cage from

his “Stories from Silence,” published by Wesleyan University

Press in 1961, and other Cage texts.) To Mr. Cunningham’s left,

Mr. Swinston takes up a position, and, just before initiating the movement

by emphatically torquing his body, he acknowledges the choreographer.

This is not so much a visual exchange as an energy exchange; a current

runs between them. It is a potent moment on its own—and was so all

along, originally being between Mr. Cunningham and Mr. Cage, launching

their separate parts of the work, which are synchronous but not interdependent

adventures. If you know the back story, the moment is now more potent

still. Continuity, change. The passage of time imposes its own narrative,

singular, but universal. That Mr. Swinston is no longer in the first flush

of youth—he is in fact somewhat older than Mr. Cunningham was when

the work premiered—but is rather an authoritative and magisterial

presence in his own right, adds resonance to the performance, and authenticity.

At

the opening of the work as it currently is presented, Mr. Cunningham is

seated at a table to the far left of the stage, on the part called the

“apron.” At his right is David Vaughan, in his own original

role as one of the narrators of the score, which is a series of vignettes,

of varying lengths, each read aloud so as to take up exactly a minute.

(Thus some are spoken rapidly, some slowly, some somewhere in between.

Sometimes the narrators overlap. The material was drawn by Mr. Cage from

his “Stories from Silence,” published by Wesleyan University

Press in 1961, and other Cage texts.) To Mr. Cunningham’s left,

Mr. Swinston takes up a position, and, just before initiating the movement

by emphatically torquing his body, he acknowledges the choreographer.

This is not so much a visual exchange as an energy exchange; a current

runs between them. It is a potent moment on its own—and was so all

along, originally being between Mr. Cunningham and Mr. Cage, launching

their separate parts of the work, which are synchronous but not interdependent

adventures. If you know the back story, the moment is now more potent

still. Continuity, change. The passage of time imposes its own narrative,

singular, but universal. That Mr. Swinston is no longer in the first flush

of youth—he is in fact somewhat older than Mr. Cunningham was when

the work premiered—but is rather an authoritative and magisterial

presence in his own right, adds resonance to the performance, and authenticity.

The choreographer was forty-six years old when he first danced in “How

To,” and his role has some of the Prospero-like, master-of-the-revels

quality with which he would imbue many of his roles in the following decade—in,

for instance, “Signals” (1970) “Sounddance” (1975)

and “Exchange” (1978). There is, however, none of the quality

of detachment or tragic odd-man-out-ness which would creep in later, during

the 80's, as in “Gallopade” (1981) and “Quartet”

(1981).The overall color of the movement is effervescent. The original

dancers wore practice clothes of their own choosing, and the stage was

stripped of side and back curtains, so that the walls of the theater itself

were the set, and whatever theatrical detritus the curtains had kept hidden

was alluringly revealed to the public. The work is performed with the

same seeming casualness today. While the dancers do not imitate football

players, there is an effect of scrimmaging–that is, of engaging

in some spirited, episodic, yet joint activity with a physical goal. While

it might be said that football has an obvious narrative content–or

at least a narrative thrust—the dance does not, but it is nonetheless

clear that the dancers are up to something. That something is movement

itself.

The fizzy, devil-may-care sensibility of the work derived, too, from the

Cage narrative, which comprises a kind of Zen entertainment, both amusing

and enlightening. For instance:

I went to hear Krishnamurti speak. He was

lecturing on how to hear a lecture. He said,

“You must pay full attention to what is being

said and you can’t do that if you take notes.”

The lady on my right was taking notes. The

man on her right nudged her and said, “Don’t

you hear what he’s saying? You’re not supposed

to take notes.” She then read what she had

written and said, “That’s right. I have it written

down right here in my notes.”

When the work was performed in New York at Hunter College, on their modern

dance series of the mid-60's, Mr. Cage wore a dark suit and tie with a

white shirt. He smoked a cigarette. He drank champagne. So, too, did David

Vaughan, who wore a dark suit and a bow tie, and was covered in wit, besides.

Today Mr. Vaughan ( a performer as well as being the biographer of Sir

Frederick Ashton and Mr. Cunningham, the Merce Cunningham Dance Company

archivist, and a critic) still declaims the same text. Now, as then, the

words and the dance have nothing to do with each other, other than overall

duration, and a unity of impression having to do with simultaneity, and

also tone. But even here, with the written word, which after all does

not change, there is a layering imposed by time passing, and roles changing.

Mr. Vaughan now dresses as an English country gentleman, appearing very

“Wind-in-the-Willows”-ish in a patterned sweater vest under

a sports jacket. Mr. Cunningham has never appeared like a country anything,

but wears quite festive attire. He is clearly not Mr. Cage, and is not

imitating Mr. Cage—his voice is low and melodious—but he does

read the stories exactly as they are written. Thus it transpires that

in telling amusing tales about his own mother (who pops up here like a

character out of James Thurber) he refers to her, as did Cage in the texts,

as “Mrs. Cunningham.” There is an even mindedness in this

distancing, but the choreographer’s tone is altogether affectionate

and touching.

As with all of Mr. Cunningham’s dances, “How To Pass, Fall,

Kick and Run” has a beginning, a middle, and an end, though not

in the way that is usually meant. There is no plot. But there is, in each

work, an arc, a shape, that constitutes inevitability. Here, after the

energy has been gathered in and dispersed, he has the last word, when—Mr.

Cunningham and Mr. Vaughan having spoken over, around, and through each

other—the narrative falls to the choreographer. “On Yap Island,”

Merce Cunningham says very slowly into the darkened theater, “Phosphorescent

fungi are used as hair ornaments for moonlight dances.” And with

that luminous pass into the end zone, he steals his own show.

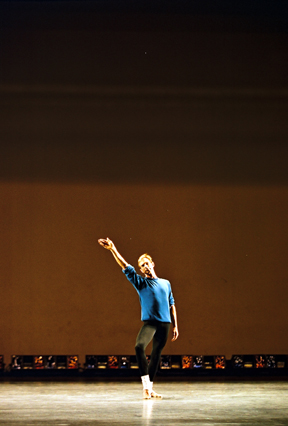

Photos:

First: How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run - 1965; Daniel Roberts and

Jeannie Steele. Photo: Tony Dougherty

Second: Robert Swinston. Photo: Tony Dougherty

Originally

published:

www.danceviewtimes.com

Volume 2, No. 36

September 20, 2004

Copyright

©2004 by Nancy Dalva

|

|

|