The Bolshoi's New, Eviscerated "Romeo and Juliet"

"Romeo

and Juliet"

Bolshoi Ballet

[Presented by CalPerformances]

Zellerbach Hall

Berkeley, California

November 3, 2004

By

Ann Murphy

copyright

© 2004 by Ann

Murphy

But then Wednesday November 3 wasn't the best day for anything. Sometimes the theater tends to ignore the temporal exigencies of politics in the service of something more enduring. Because of that I dutifully, if miserably, traipsed off to Zellerbach Hall at half past seven, only to become more miserable when I discovered that the curtain had gone up at 7. The day was moving toward the surreal, and when I entered the theater during a cartoonish chapel scene, soon followed by the ballet's carnival scene, I was met with a strange combination of modernism and early 20th century vaudevillian fizz, contemporary seeming steps and vacuity. The former Soviet, antediluvian company, which 30 years ago boasted dancers with enormously overdeveloped legs from a Draconian scheme of weighting their ankles during class, was performing a quasi Bausch-ian, Prejlocaj-ian, Fokine-esque, Robbins-ish "Romeo and Juliet" to a radically squashed version of the Prokofiev score (played with crystalline beauty by the Bolshoi Orchestra, its brass section glinting).

Clearly, the Bolshoi was finally, if awkwardly, moving into late 20th century dance at the dawn of the 21st century. Its new director, Alexei Ratmansky, who came on board after this "Romeo" was commissioned, has already shown himself a witty and winsome choreographer in his "Carnival of the Animals," created for San Francisco Ballet in 2003. But the 21st century is already proving highly problematic, and well into the middle of the Act I, so was this "Romeo." Crowds of men and women ran around portentously like actors from 1920's Berlin theater, or hovered over a horizontal wall like bobbing dolls. Meanwhile, the famous lovers, dressed modernly in white and ice blue-he in loose pants and jacket, she in shorty-style silk pajamas—stretched into jazzy side-long piques and rounded over in simulacrums of an angst I was feeling all too strongly. It was immediately clear that Mr. Poklitaru, who graduated from the choreographer's school of the Byelorussion State Academy of Music, has oodles of contemporary moves in his dance bag. But Angelin Prejlocaj put his Orwellian version on the map long before this young choreographer from Kishinyov met up with the British director. What was clear was that Mr. Poklitaru was showing off how much and how little he knew and Mr. Donnellan was not helping matters.

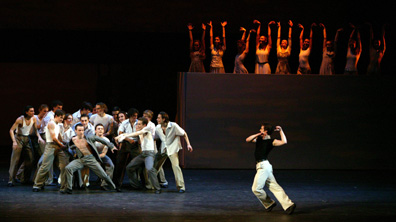

In a way reminiscent of Universal Ballet's version, and propagandistic styles in general, this was a production of "Romeo and Juliet" about erotic and individual love that was neither erotic nor psychologically driven, set not against family or warring tribes but an undifferentiated and conformist mass of bourgeois society. As far as the eye could see, there was no greater intellectual nuance than that, and the team's idea of an Orwellian threat to individual freedom from mass conformity was about as developed as our media's turns out to be.

On a playing field of such didactic black and white, and minus the intensifying complexity offered by Shakespeare's cameo characters (another parallel to Universal's production), the choreographer set about moving blocks of dancers about the stage like hunks of molten construction material. Sometimes they would scoop up or swallow an "individual." Generally they and the handful of characters existed in separate but indeterminate spaces, even when they physically intermingled. Mr. Poklitaru and Mr. Donnellan also seem unclear what the role of repetition is as they endlessly reiterated group's phrases with no cumulative effect other than to leave the viewer worn out. This occurred both within sections and over the course of the night, and before long, the vaudevillian irony Messrs. Poklitaru and Donnellan hoped for turned pallid and meaningless. It reminded me of someone speaking a language fluently without knowing what it signifies.

Mr. Poklitaru, Mr. Donnellan and Mr. Ormerod had plenty of good ideas. The spare set with one horizontal wall and one central rectilinear column could have given the drama the austere dimension of Greek tragedy (although the lighting levels were often far too low). But to have measured up to the scenic demands, the dance would have had to have been essentialized, not merely minimalized. Instead we got images such as a clot of people in black standing stone still against the stark red wall as the lovers wrapped themselves in and covered their heads with a sheet, or two halves of the crowd capturing and holding the lovers aloft, as Mark Morris does in his "Hard Nut." But eviscerated of emotional logic and kinetic drive, the images turned instantly into clichés, and strikingly dated ones.

One wonders: what do lovers signify to Messrs. Poklitaru and Donnellan? When loving is dangerous in society, the crime they commit is the crime of desire, but desire seemed veritably absent between these teenagers. Except for Romeo's predatory fingers spidering across Juliet's body, which was sexually creepy, there was little sizzle there at all.

For Shakespeare, the themes of personal and group freedoms are intimately connected. He embodies important gradations of humanity and liberty in his characters, from the benign liberating Nurse, to the antihumanitarian Tybalt, and these embodiments give cold concepts flesh and blood truth and drama. Tyranny, Shakespeare demonstrates, is designed by idiosyncratic individuals (imagine Karl Rove as Tybalt and Lynne Cheney as Lady Capulet) and endorsed and enforced by an entire system (Diebold voting machines).

Unlike Mr. Prejlocaj's 1989 "Romeo and Juliet" for Lyons Opera Ballet, in which the authoritarian state is rendered by a massive set that seems to take us from the Industrial Age to Foucault's vision of society as a panopticon prison, and in which he uses different dance genres to align social classes and interests with certain characters (the Nurse, for instance, made double, wore wonderful Chanel-like dresses and danced Diaghilev-era steps), Mr. Poklitaru and Donnellan seem to have no real politics in which to root their version. Nor do they convey any visible understanding of the origins of the dance styles Mr. Poklitaru glibly employs. What a shame.

With all that said, some of Mr. Poklitaru's phrases for the crowd, especially the women's group phrase of deep second position plie jumps, hands on thighs, topped by sexy, undulant spines, advancing like a chorus line of erotic bugs or dance hall girls, had a nice irony about it. And the group dance based on figure-eighting arms performed in front of the face combined with a kind of fish wiggle in the body, although Bauschian, was charming. Crowds can be enticing.

But what one wonders is whether Mr. Poklitaru has any vocabulary that is uniquely his and if not why not? All the interesting movement looked derivative. What I call the plow step from Graham was there, performed en masse. A gloss from Westside Story's women's flamenco number cropped up. Romeo's attempt to make comatose Juliet dance with him was a watered down version of Mr. Prejlocaj's heartbreaking scene of loss. And when the steps or phrases didn't seem derivative, there was often an absence of movement that was downright weird. Paris was cast as a creepy guy in British wedding clothes, replete with top hat, and behaved like a magician as he tried to take charge of Juliet, gesturing as though pulling things out of his pockets, or making things disappear, then kissing her up her arm like a cad in a silent film. Juliet's response? She bit him. In the theater that might have weight, but as a dance gesture, unless surrounded by more content than that, it's an act of desperate literalism. And given that a theater director was the leader of the team, according to an online interview with Mr. Donnellan, shouldn't he have allowed Mr. Poklitaru to embody her revulsion in actual dance language? Apparently Mr. Donnellan thinks dancers are too tied to movement, and actors too tied to language. When later "Romeo and Juliet" looked across the stage space like lost puppies sniffing the air, gazing past each other in the silence, I kept wondering: what are the couple waiting for? Some music?

Juliet's anemic role must have been difficult to fill out, but Maria

Alexandrova conveyed little inner conviction and seemed to be propelled

by her autonomic system rather than her glands or her guts as a nearly

14-year-old girl would be. Lanky Denis Savin's Romeo and the gangsterish

Tybalt, performed with great slimyness by Denis Medvedev managed, by contrast,

to be quite compelling. They inhabited the off-kilter steps and sexy pelvic

expressiveness with puppy dog cool and Cagneyesque suavity respectively.

The corps also deserves credit. They performed movement they hadn't fully

internalized, dances that at times reminded me of high-end summer stock,

and did it with the earnest intensity of professionals.

What probably stumped me most of all was that despite the clanking inability

to use stage volume well or to give anything but decorative menace to

the crowd's steps, Mr. Poklitaru and Mr. Donnellan could be so utterly

hopeless with Romeo and Juliet themselves. The love scene reduced the

couple to dancing cut-outs leaping on and off a bed. Rather than imagining

the depth and intensity possible in their lovemaking, as the best pas

de deux can do, I was led to think that medical probing with cold stainless

steel instruments seemed more interesting than whatever contortions they

were into. German political theorists warned a long time ago that libidinal

sensuality dies in the authoritarian state. My question: does it ever

return?

Romeo & Juliet PHOTO: Damir Yussupov

www.danceviewtimes.com

Volume 2, No. 42

November 8, 2004

Copyright

©2004 by Ann Murphy

|

|

|