Deca

Dance

Batsheva Dance Company

America Dancing, Kennedy Center

Eisenhower Theater

Washington, D.C.

Feb. 26-27, 2004

by

Lisa Traiger

copyright 2004 by Lisa Traiger

published 1 March 2004

Ohad

Naharin likes to line up his dancers across the front of the stage letting

them spout off tightly packed phrases of movement, sequentially or, to

increase the effect, all at once. This is how his Deca Dance

opens and the formation returns in different costumes with different movement

over the course of the evening. It's as if Naharin wants to break down

that invisible but necessary barrier between performer and audience. And

then he does.

Ohad

Naharin likes to line up his dancers across the front of the stage letting

them spout off tightly packed phrases of movement, sequentially or, to

increase the effect, all at once. This is how his Deca Dance

opens and the formation returns in different costumes with different movement

over the course of the evening. It's as if Naharin wants to break down

that invisible but necessary barrier between performer and audience. And

then he does.

During the second half of Deca Dance, his conglomeration of nine works dating from 1985 through 1991, the Batsheva dancers do break down that wall when they stroll into the audience and select a dance partner. Back up on stage the professionals, in dark suits and white shirts, twirl and tango, dip and lift their unsuspecting partners. One forty-something man Thursday evening found himself lifting a petite lady, her legs entwined around his waist. The beauty of this segment of Deca Dance, originally performed in Anaphaza (1993) was in the way these exquisite Batsheva dancers made even the most rank of novices look good. You saw new meetings, intimacy and the innocent abandon of simple dances, as well as discomfort, uncertainty even a touch of embarrassment. And the audience ate it up, uncharacteristically—for the Kennedy Center—applauding and whooping at the sight of their fellow dance watchers become part of the action, the art making up on the Eisenhower Theater stage. Naharin tells us in his typically rule-breaking manner that we are all, in fact, dancers. There's no difference between the 16 men and women on stage and the rest of us sitting out in the red seats watching them.

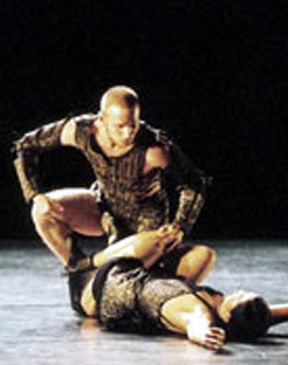

But there is a world of difference. The Batsheva dancers are a fearless and dedicated bunch. Their dancing has a trenchant and boundary-pushing quality not typically seen in many American companies. There's no loosey-goosey release technique going on here, none of the breathy, over-easy phrasing now so popular among a cohort of American post-post-moderns. The Batsheva dancers perform with a clarity and specificity that defines their movement quality along with a fearless push-to-the-limits approach.

And in Naharin's work they need that edgy physicality. Deca Dance is a collection, but not a retrospective. Instead Naharin reworked and revived, jiggered sections of his favorite choreography into a new piece, small parts into a new whole. Yes, there are jewels here among the admixture, but in its entirety the work seems piecemeal, a crazy quilt and, as one section blends or shifts to another, changes in tempo, music, tone, costume sometimes jar the onlooker's sensibility. (And Naharin probably doesn't mind that either.) Ultimately, though, if one's unacquainted with the body of Naharin's work, it all seems much like gibberish.

Dancers

clutch, kick, grab, squeeze themselves into oddly realized positions,

their limbs flexed, flayed, self-flagellating in a little series of pelvic

contractions. In a section from Black Milk when five men mark

their bare-chested bodies with black paint it's some ritualistic ceremony

but, coming after a section from another dance, in modified Renaissance

bustiers, Mabul (Flood) maybe, the mystery and resonance is denuded. There

are social dance sequences that become something else again, with their

mid-century pop songs, retro-sounding but somehow new again in the context

of the dancers' pushy, twitchy edgey approach to pairing up and parting.

Dancers

clutch, kick, grab, squeeze themselves into oddly realized positions,

their limbs flexed, flayed, self-flagellating in a little series of pelvic

contractions. In a section from Black Milk when five men mark

their bare-chested bodies with black paint it's some ritualistic ceremony

but, coming after a section from another dance, in modified Renaissance

bustiers, Mabul (Flood) maybe, the mystery and resonance is denuded. There

are social dance sequences that become something else again, with their

mid-century pop songs, retro-sounding but somehow new again in the context

of the dancers' pushy, twitchy edgey approach to pairing up and parting.

A series of solos, each one exquisite in its own right, allow the Batsheva women to demonstrate their pinpoint accurate attack along with a more languid, sensual side. Additionally, the small focus of these dances for one allows for individualized characters to simmer forth and, amid the clutter of the nine shifting works that form Deca Dance, these solos come on small and fine, something to be grasped and hung on to against the rush-rush force of the larger landscape Naharin has shaped.

Then there's the controversial section that cause political protests in Israel. Naharin at the post-performance discussion discounted the whole thing as a storm in a glass of water. The dark suited, fedora hatted dancers sit in a semicircle and perform an accumulation, adding a movement as the song progresses. The song, a heavy duty rock version of "Echad Mi Yodeah?" ("Who Knows One?"), a Hebrew Passover seder song akin to "The Twelve Days of Christmas" seemed to cause many then and in the Kennedy Center audience problems. Queries about that section were foremost during the after-show chat.

The dance itself is a smart collection of movements. Its repetition and accumulation allow it to build itself into a near frenzy. As the dancers rise and sit in quickly linked succession, their arms flinging skyward as the heavy-metal pulse of Tractor's Revenge spouts those godly verses in Hebrew, images of a firing line come to mind. And for an Israeli company it's no wonder that other disturbing images, of current day and past political events, infiltrate what Naharin calls a purely compositional form.

But

Naharin, who tags all his inventive movement as "research in composition,"

is perhaps more than a touch disingenuous. He knows that movement carries

meaning, that it doesn't lie and that it communicates on a purely visceral

level. His dances are full of that heady, visceral stuff of life—love,

sex, violence, ambition, hanging on and letting go. What happens in Deca

Dance is that whatever residual meaning that could be had from seeing

one or two of these nine works in its entirety has been lost in the compositional

mush of his endeavor to rethink and rework elements into a new dance.

Deca Dance, the title, hints at decadence. Again, Naharin, I

think, is disingenuous. Perhaps, on the surface, viewers can take in the

roughly executed, heady dancing as violent, decadent, but look deep and

there's nothing depraved about it. Rakefet Levy contributed beautiful

costumes, aside from standard shifts and dark suits, including body hugging

mannequin like leotards, short-skirted, open shouldered pieces for the

women, and loosely flowing muslin pantaloons for the men. Frankie Lievaart's

sound engulfed the Eisenhower, at points almost assaulting delicate eardrums

in some of the harsher rock influenced musical selections. Naharin's music

choices ranged from Arabic oud and flute music, operatic and classical

selections from Vivaldi to Beethoven, contemporary classics by Arvo Part,

and pop and commercial standards from Harold Arlen and Dean Martin and

more. Avi Yona Bueno-Bambi's lighting shaped and highlighted the dancers

but in other theaters his work has shone more brilliantly.

But

Naharin, who tags all his inventive movement as "research in composition,"

is perhaps more than a touch disingenuous. He knows that movement carries

meaning, that it doesn't lie and that it communicates on a purely visceral

level. His dances are full of that heady, visceral stuff of life—love,

sex, violence, ambition, hanging on and letting go. What happens in Deca

Dance is that whatever residual meaning that could be had from seeing

one or two of these nine works in its entirety has been lost in the compositional

mush of his endeavor to rethink and rework elements into a new dance.

Deca Dance, the title, hints at decadence. Again, Naharin, I

think, is disingenuous. Perhaps, on the surface, viewers can take in the

roughly executed, heady dancing as violent, decadent, but look deep and

there's nothing depraved about it. Rakefet Levy contributed beautiful

costumes, aside from standard shifts and dark suits, including body hugging

mannequin like leotards, short-skirted, open shouldered pieces for the

women, and loosely flowing muslin pantaloons for the men. Frankie Lievaart's

sound engulfed the Eisenhower, at points almost assaulting delicate eardrums

in some of the harsher rock influenced musical selections. Naharin's music

choices ranged from Arabic oud and flute music, operatic and classical

selections from Vivaldi to Beethoven, contemporary classics by Arvo Part,

and pop and commercial standards from Harold Arlen and Dean Martin and

more. Avi Yona Bueno-Bambi's lighting shaped and highlighted the dancers

but in other theaters his work has shone more brilliantly.

Originally

published:

www.danceviewtimes.com

Volume 2, Number 9

1 March 2004

©

2004 Lisa

Traiger

|

|