Moving

Arts Dance

Yerba Buena Center for the Arts

San Francisco, California

April 24, 2004

By

Rita Felciano

Copyright

© 2004 by Rita Felciano

published 26 April 2004

Should

there be a competency test for choreographers before they are allowed

to use certain musical scores? The Balanchine Trust determines whether

a company has the ability to perform one of Mr. B's pieces. Some years

ago Elliot Feld couldn't get the rights to a Richard Strauss composition.

He had to perform the choreography in silence. And composers not uncommonly

encounter a firm "no" when they approach wary poets—or

more commonly their estates.

Should

there be a competency test for choreographers before they are allowed

to use certain musical scores? The Balanchine Trust determines whether

a company has the ability to perform one of Mr. B's pieces. Some years

ago Elliot Feld couldn't get the rights to a Richard Strauss composition.

He had to perform the choreography in silence. And composers not uncommonly

encounter a firm "no" when they approach wary poets—or

more commonly their estates.

Beyond the legality of using copyrighted material, shouldn't choreographers be held to minimum standards, much like would-be Balanchine dancers? Should anybody be allowed to tackle Stravinsky, Ligeti or the Sacred Chants of Tibet? Most long-dead composers don't have estates to protect (and cash in on) them.

Of course, the analogy is not quite right. Most music is written down, mechanically reproduceable and as such less fragile than a dance. And great music has proved to be remarkably sturdy. It can stand assaults of many types.

Still there is something deeply disturbing about arrogating to yourself the right to someone else's work and trying to cash in on it without adequate preparation. Mark Morris, George Balanchine and Paul Taylor know the music they use inside out. They don't ride its surface appeal. It took Brenda Way thirty years of dance making before she tackled Bach's "Goldberg Variations." Not only do these choreographers treat the music with utmost respect, they re bringing to it love and understanding as well as their own dancemaking skills. These artists ultimately can enhance our understanding, or change the perspective as Taylor does, of great music.

Which brings us to Viktor Kabaniev, whose abuse of Beethoven and Wagner twelve hours after the fact still rankles.

The Soviet-trained Kabaniev, formerly of Diablo Ballet, is a respectable dancer with a flair for dramatic expressiveness. Together with Tina Kay Bohnstedt (who continues to dance for Diablo), and Michael Lowe, Ethan White and Erin Yarbrough from Oakland Ballet, Kabaniev moved to Moving Arts Dance, a company that essentially grew out of and still is associated with a Walnut reek dance center. Artistic Director Anandha Ray for some years has struggled to bring her semi-professional dancers to the next level. The infusion of these professionals, some of them excellent, Yarbrough and Bohnstedt in particular, now seems to make this possible.

What the company needs to get, and the sooner the better, before their freshly found momentum peters out, is a decent repertoire and a sense of scale. The Friday night concert lasted almost two and a half hours. It consisted of seven pieces (actually nine since in two cases two of them were fused into one), in addition to a fifteen minute encore, At Arm's Length by two guest artists Victoria Baltser and Alexander Tebenkov from Belarus.

This latter dance theater work actually proved memorable. With its restricted, but carefully chosen movement material from a wide variety of sources, this piece had fresh, nicely structured ideas about how people get together or not. It started out in a light commedia vein but turned very dark.

Right now Moving Arts Dance is a vehicle for its three resident choreographers, Ray, Kabaniev and Michael Lowe. Though quite different from each other, they are committed to something probably best be called contemporary ballet-ballet based dance with limited use of the academic language and an infusion of modern dance and other influences.

Lowe

tries to perfume ballet with an Asian flavor. Somewhat obsessed by athletic

partnering moves, his choreography is quite simple and straighforward.

He nevertheless is musical and works with a good sense of space and patterning.

The showy Jutze ("Stalk"), the pas de deux from his

full-evening Bamboo, was energetically performed by Yarbrough and White.

Set to traditional Chinese folk music, unison moves drew the dancers from

opposite sides of the stage until their bodies intertwined in rather tricky

partnering moves. Those nicely flowed into one another despite some moments

of insecurity.

Lowe

tries to perfume ballet with an Asian flavor. Somewhat obsessed by athletic

partnering moves, his choreography is quite simple and straighforward.

He nevertheless is musical and works with a good sense of space and patterning.

The showy Jutze ("Stalk"), the pas de deux from his

full-evening Bamboo, was energetically performed by Yarbrough and White.

Set to traditional Chinese folk music, unison moves drew the dancers from

opposite sides of the stage until their bodies intertwined in rather tricky

partnering moves. Those nicely flowed into one another despite some moments

of insecurity.

For Upstream/Splashing Fish Lowe created a trio of the type that means to give young dancers (Barbara Giusti, Devon LaRussa and Holly Morrow) an opportunity for solo work and to show that they can partner each other. The first section also framed a duet from Lowe's 2003 Double Happiness, choreographed for Oakland Ballet. Again performed by Yarbrough and White, its softly expressive tone communicated ease. Yarbrough's classical technique is still in fine shape.

In addition to having designed some of the excellent costumes, Ray showed two works. The very long The Letter, which is a work in progress, did not really belong on this program. It involves the anguish a letter can produce in both writer and recipient, particularly if it falls into the wrong hands. At this stage five women dancers are involved.

The nicely arched From Heaven, a duet for Bohnstedt and Kabaniev, used music by the Tin Hat Trio. Highly expressionistic, the work called up a dream world in which a woman remembers her dead husband. The emotionally dense encounters shifted between tangible being in touch and escaping each other's grasp. Crouched to the ground, Bohnstedt's intense grief seemed to bring Kabaniev back to the point where they were in the presence of each other's bodies.

As a choreographer, at least judging from local showings, Kabaniev is the least experienced of the three.

The major issue I have with his work so far is that he chooses music of considerable impact—though I am no great fan of Arvo Part's overused Fratres—and does not even attempt to engage it. He rides a score's surface and uses its emotional impact to support choreography which is paper thin and relies on obvious theatrical gestures.

In

Fratres, which is all surface, it didn't matter. That's the reason

maybe why the "White" section, from White Light, was

the best of the works he showed. A duet for two ballerinas in frumpy tutus

and knee pads (LaRussa and Morrow), it showed the dancers in blackout

interrupted poses of various degrees of disheveled awkwardness. The piece

seemed to develop along a theme of awkwardness, collapsing and lack of

balance which may relate to the fact that it was originally created as

a tribute to a fellow dancer who died.

In

Fratres, which is all surface, it didn't matter. That's the reason

maybe why the "White" section, from White Light, was

the best of the works he showed. A duet for two ballerinas in frumpy tutus

and knee pads (LaRussa and Morrow), it showed the dancers in blackout

interrupted poses of various degrees of disheveled awkwardness. The piece

seemed to develop along a theme of awkwardness, collapsing and lack of

balance which may relate to the fact that it was originally created as

a tribute to a fellow dancer who died.

For "Light", on the other hand, Kabaniev went to Wagner's Liebestod from "Tristan." He had the lovely Bohnstedt, in white panties, camisole and knee pads, rise from a shoulder stand to light a lantern. Gradually through a series of scooping gestures, jetés and drops, she worked herself towards the back of the stage. As the waves of music rose to its climactic—some think its orgiastic—highpoint, she was hanging and flailing against a wall which she presumably had tried either to climb or pull down.

Thematically On Beethoven's Music—inspired apparently by listening to the composer while in Hawaii-—appears to depict a life's journey from youthful happiness to the dashing of hopes by the interference of fate and a final reconciliation. The piece opened with young women sitting at the apron, sewing wedding veils which they pinned on themselves, nicely on the down beat. A fate figure (Ray) dragged herself across the stage at which point the girls individual cavorting came to an end. They put on long black (Grahamesque?) dresses and pulled themselves around in unisons. Two male dancers (Lowe and Miroslav Pejic) seemed to act as instigators of change but their dashings didn't make much thematic sense. Bohnstedt, lovely in her solitary and silent concentration and reaching, was the one who brought about a communal reconciliation.

Of course, the excerpts of the Beethoven symphonies, most prominently from the Pastoral and the Seventh, and the Pathetique piano sonata, sounded glorious. But the steps were rudimentary; there was not enough emotive power through movement to create anything even approaching the grandeur that Kabaniev purported to pay tribute to. If he wants to continue using world class music, he needs to dig deeper inside himself. He might also do something as simple as take a class in music appreciation.

Photos:

First: Moving Arts Dance Associate Artistic Director and Resident

Choreographer Viktor Kabaniaev, photo by Scott Belding.

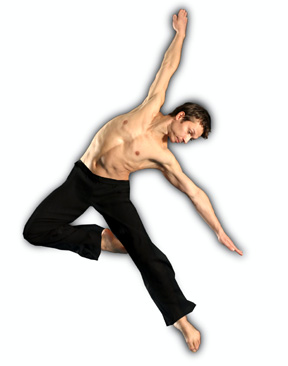

Second: Moving Arts Dance Resident Choreographer Michael Lowe, photo

by Scott Belding.

Third: Holly Morrow in The Letter, choreographed by Anandha

Ray, World Premiere 2004, photo by Scott Belding.

Originally

published:

www.danceviewtimes.com

Volume 2, Number 15

26 April 2004

Copyright ©2004 by Rita Felciano

|

|